リズ•トーマスのハイキング•アズ•ア•ウーマン#01 / 私が『ハイカートラッシュ』になるまで。

■About Liz

For the past eight summers, I’ve left my comfortable home to go on mountain treks that make me extremely cold or hot, smelly, and hungry. I carry everything I need on my back, sometimes walking for months on end. But it wasn’t always like this. How did I go from living a typical, suburban life to becoming someone who hikes in the woods for months each year? Surely, my school age self never would have predicted that I’d be traveling all the time, scraping by to pay my bills, and loving every moment of life. Yet, as I think about my experiences growing up, I can see how thru-hiking is the culmination of the interests and values I’ve had my entire life. When I discovered long distance hiking, it felt natural to me. Here, I explain how I left a “normal” American lifestyle and became what is affectionately known in the hiking community as “hiker trash.”

I was not raised in the outdoors. My mom is Japanese, born and raised in Japan, and although my family had a respect for nature, I was not raised to be athletic or outdoorsy. Instead, my mom was a kyouiku mama, so I was expected to spend my time as a child studying and practicing piano. Like many American suburban girls growing up in the ‘90s, “fun time” meant going shopping at the mall. My childhood house was crammed with stuff and for many years, I believed in the typical American dream that accumulating more stuff is the way to happiness. However, I never felt like buying more things actually seemed to work.

The thing that did make me happy, however, was not a thing. It was experiences, especially trips anywhere in nature. I enjoyed riding my bike and walking, but had few opportunities to do it. Unlike in Japan, most people drive cars everywhere in suburban California, where I was raised. The infrastructure in my city was not designed for bikes or walking, so my parents did not think it was safe for me as a child to go outside by myself. If I wanted to go outdoors, I would have to wait for my parents to drive me to a park where I could play—but this only ever happened on the weekends when my parents were not working. As a result, I spent a lot of time playing indoors, watching TV, and playing computer games.

But even then, I found ways to be with nature. I loved being outdoors so much that I incorporated it into my 8th birthday party. When other 3rd graders were holding birthday parties at the bowling alley or the local amusement park, I had a more adventurous plan. A few weeks before my big day, I handed everyone in my 3rd grade class an invitation to meet at the small, local nature area at 5:30 AM for a birthday hike. Not many people showed up, but those who did had the joy of fresh air, a bit of exercise, and time communing with wild deer and turkey before we hit up a greasy breakfast fast food joint. It seems uncanny how similar that birthday party was to the thru-hiker life I lead now!

When I was in 5th and 6th grade, my family took two trips to Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park. We stayed in tent cabins and day hiked shorter trips, which were difficult for me as I was among the least fit people in my elementary school class. Still, I loved hiking and scrambling up rock formations and found exerting myself to reach a goal immensely rewarding. Before these trips, I had associated being active with being wealthy. I attended a prestigious elementary school where my classmates’ parents owned big companies and the other kids exercised by swimming and playing tennis at exclusive country clubs. In nature, I learned that achieving physical goals doesn’t mean you need to spend lots of money or be related to a CEO. Nature itself is a free gym where everyone can challenge themselves.

Around this time, I spent two summers living with my grandparents in Nikko, Japan attending elementary school there. Each morning, we would walk across town to school with other students from our neighborhood. While at first this was annoying—in America, I had always been driven to school—soon it became a highlight of the day for me. I enjoyed living in the mountains and the freedom of walking around outdoors. Living in Japan taught me the simple pleasure of walking as a form of transportation and when I returned to the U.S., I yearned to experience once again a culture that valued walking.

By the time I went to high school, I was finally allowed to bike by myself, but was too busy to have much time to dedicate to that hobby. I was on the varsity water polo team in the fall and varsity swim team in the spring and also sang in a prestigious choir, took extra classes, studied art curation, and was a captain of the high school mock trial team. My high school was very competitive and burnout was common. Biking in nature helped me de-stress from school, and so on weekends when it wasn’t swim or water polo season, I would hit the bike trail.

Throughout high school, I felt like I was so busy with my extracurricular activities and classes, yet none of the things I was spending my time on really called to me. I wanted to travel and felt confined and restless in my hometown. I wanted bigger landscapes and bigger adventures. During summer vacation, I would spend every day cycling as far as I could, usually around 100 km along the river until I started to see open space. Sometimes, I would ride the city buses to the end of the line just to visit someplace new. My mind was eager for exploration. I have always been curious go to new places and learn from travel, even if that new place is only 30 km from my house.

The summer before college, I went on a month-long trip to Europe with my German class. It was definitely a budget trip—we stayed at hostels and wandered around Europe with backpacks—but I loved it. I relished seeing new places, meeting new people, and carrying everything I needed on my back. I savored never staying in one place for too long, being ever moving, ever exploring. Of the 16 students on the trip, my pack was the lightest, which afforded me the freedom of ease to explore more places. Since it was so light, I volunteered to carry another student’s bags as well, as long as she would fund my addiction to European chocolate bars. I believe it was this early experience carrying a light pack that taught me the advantages of being ultralight on adventures.

Determined to take a similar trip in the country I lived in, but had barely seen, the next summer, I worked hard so that I could take a month-long train trip across the U.S. At 18, I traveled solo across the country with only a backpack. In a few cities, I had friends to stay with, but in most cities, I had to navigate the public transit and streets alone, in a time before cell or smart phones. Before the trip, I checked out stacks of books from many libraries and spent months studying maps, bus routes, and guidebooks. Once again, I loved living out of a backpack and always being on the move. I lived to see new places and learn what they had to teach me and I enjoyed the process of planning and executing a big adventure.

For college, I went to a competitive school and got very good grades. My professors encouraged me to pursue a PhD, and my success should have made me happy, but I had a hard time making friends. I didn’t enjoy partying and I needed something other than classes to be passionate about. My school was in Los Angeles and I didn’t own a car, but I woke up at 6 each morning and, over time, explored the 80-mile radius area around my college on bike. But I wanted to explore wilder and natural landscapes, so I took a college PE class in rock climbing.

Soon, rock climbing became a passion for me. I went to the climbing gym almost every day after class and work. Initially, I climbed with other college students, but found that young people often let homework or parties get in the way of serious climbing. Soon, my regular climbing partners became a group of grisly mountaineers, mostly in their 60s. These old men taught me outdoor skills and took me on adventures to climb big mountains. Our party of climbers must have looked a little strange to outsiders with me, a 19-year-old girl, alpine climbing big peaks in the High Sierra with grizzled mountaineers. I owe a good deal of my outdoor skills to these adventurers, who patiently and generously taught me to peakbag technical and non-technical mountains.

As part of my training, one of the old men explained, “We hike to keep weight off so that we can climb better.” This inspired me to take advantage of the 3,050-m mountain right above my school, so as soon as I got a car, I got into the habit of going to bed early, getting up at 5 am, and hiking up it before class as practice for bigger trips. As college went on, I spent more and more time outdoors or riding my bike and a lot of time in the climbing gym. I took wilderness medical courses and learned as much as I could about safety in the outdoors. Later, I even scheduled my classes so that they were only 3 days a week so I could spend 4 days a week hiking and climbing in the Sierra.

For three summers, I worked doing environmental research in the Eastern Sierra right outside Yosemite. It’s my favorite place in the world and an excellent place for peakbagging and climbing. My first year working in the Sierra, I returned to Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park and started talking with two dirty, tired hikers. They said they were hiking the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) from Mexico to Canada and that they were already beat, done, ready to quit. They said that 3 of the 100 people who started the PCT that year had died already. For some strange reason, my enthusiastic response was: “I want to do that!” From that point on, whenever I saw PCT signs on my peakbagging trips, I got increasingly excited about taking the trail all the way to Canada. When I returned to college, I would hole up in my dorm room reading trail journals and stories about thru-hikers. I spent my nights in college fantasizing about the PCT instead of partying.

The fall of my senior year, I taped two sheets of paper on my dorm room wall: “Climbing goals” and “Hiking goals.” Every minute I wasn’t studying, attending class, or working, I was training to achieve these goals. I would even do my class reading while stretching or working out. But after several months, a finger injury forced me to focus all my energy on hiking. My hiking trips were all peakbagging—ambitious traverses with more than 3,000 m of elevation gain a day—often with three or more peaks summited in a less than 24 hour trip. I started the semester with the easiest of these hikes, and by fall break, I became the first recorded person to hike the three highest peaks in Southern California solo, without a support team driving between the mountains. In hiking, I found “flow”—a feeling where I was fully immersed in my goal and energized by the focus required to achieve it. Still, by the time my finger healed, climbing was back to being my main activity.

After I graduated, I worked my last summer in the Sierra as a “good bye” to the free outdoor life I had been living. I knew that when this summer was over, it’d be time to hang up my backpack and start working in a cubicle. I climbed in my off days, but a big lead climbing fall, a few late night finishes on alpine climbing trips, and one poorly set up anchor were enough to convince me to focus more on hiking for the second half of the summer. That July, I decided to hike the 265-km long Tahoe Rim Trail solo. It was only my second outdoor backpacking trip ever, but by this time, I had done so much travel-backpacking and camping at climbing crags that the transition to outdoor backpacking didn’t seem like it would be too harsh. I carried the lightest pack I could manage—14 kg with food and water—and set an aggressive goal of hiking 45 km per day.

As I fell asleep each night, I was terrified of bears knocking down my pitiful attempt to hang my food bag. By the second night, my stove wouldn’t function. On my third day, I ran out of food and needed to buy more. On my fifth day, I ran out of water and had to sneak some from a sprinkler at an upscale mountain condo. For the first time in my life, I had to take a pain killer because the pounding in my feet was so bad. Yet I made it. I had just finished a thru-hike completely solo, and I was absolutely exhilarated.

After I finished, I realized that compared to a thru-hike, a dayhike—even a long dayhike, is stressful. I now believe it takes at least two weeks of thru-hiking to clear my mind from all the anxieties of the “real” world. Dayhikes have too many distractions to be a mediation. Only thru-hiking—walking free of cars, computers, and most obligations—can free my mind of so many worries. When I am thru-hiking, I feel alive.

At that time, thru-hiking the Tahoe Rim Trail was one of the hardest things I’d ever done in my life, but I was hooked, and immediately started planning my next thru-hike. In everything I’d done in my life up to that point, I felt like I was fighting or doing something unnatural for me. After so much time shopping in malls, practicing piano, and studying, I had finally found something that felt like what I should be doing.

After that first thru-hike, I knew I couldn’t enter a cubicle now. Thru-hiking has become the meaning of my life—enjoying the meditation of walking in beautiful places and living simply in nature. It provides me with freedom but also the integrity gained by self-reliance. Though I own little as a thru-hiker, I always live well. Now that I have seen how good life can be, I am determined to do what it takes so that I can spend my summer living my life honestly by doing work that is my own: hiking in nature.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

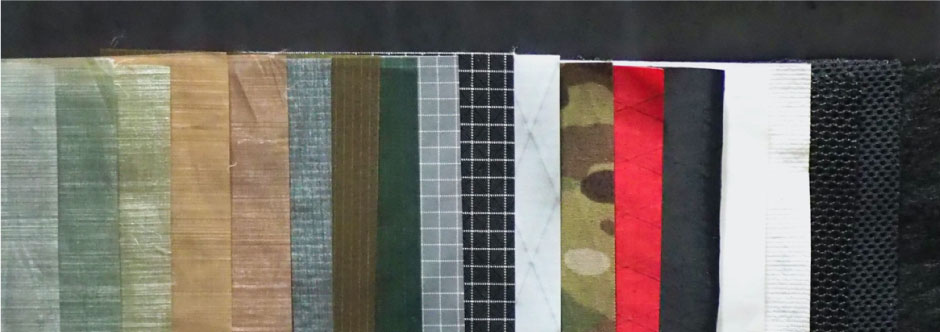

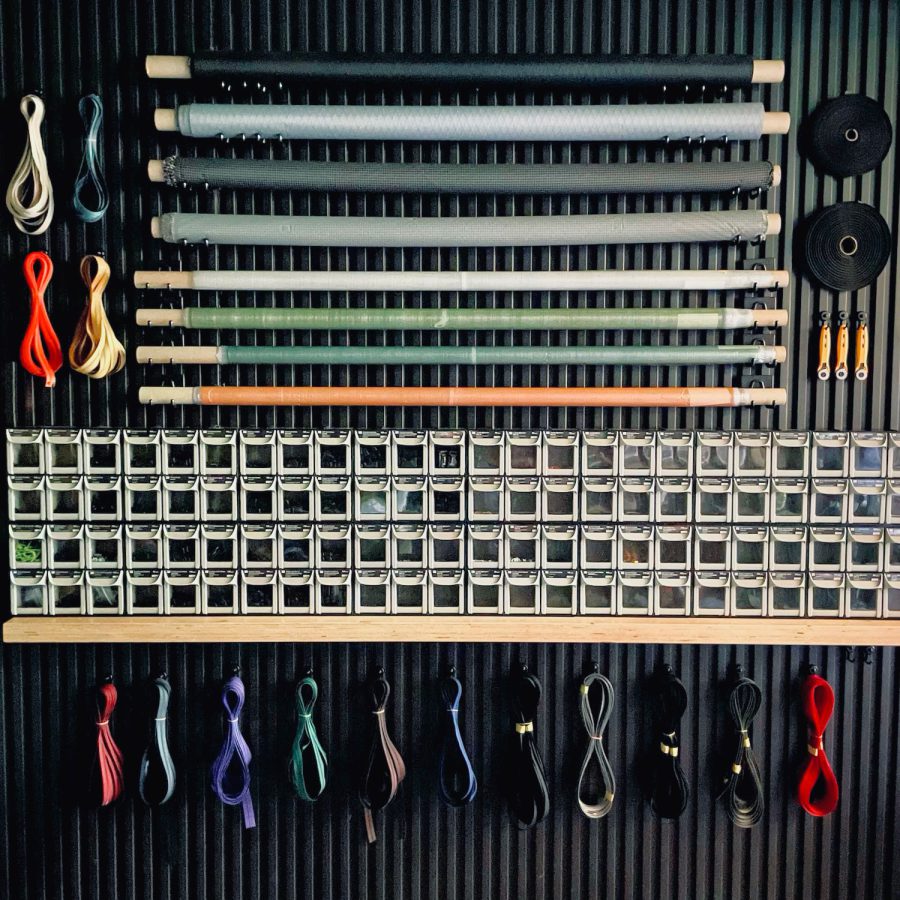

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…