リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#09 / グレート・ディバイド・トレイル(その1)

Great Divide Trail: Part 1

This summer, I mustered the courage to hike a trail that I had spent many years fearing. I set off on a journey where I wasn’t quite sure I’d make it back home in one piece. It’s a trail that only attracts 30 or so people per year to attempt it and many hikers fail. I had spent my hiking career trying to avoid a lot of the key challenges of this 1,200 km trip across the Canadian Rockies: grizzly bears, big river fords, snow, bushwhacking, tricky navigation, and the challenges of hiking internationally.

Yet, somehow, despite all the anxieties I felt towards the Great Divide Trail, I decided to give it a try. I blame a few dreamy photos posted online by a friend who hiked the trail last year. The beauty of those photos lingered f in my head all throughout the winter, slowly making my desire to see the views swell over my dread of its challenges.

Half in jest, I mentioned to my friend Naomi that we should hike the Great Divide Trail together. She had been planning to spend the summer hiking the Pacific Crest Trail solo southbound—her second hike of the PCT. “Why would you want to hike a trail you’ve already done?” I asked her, mostly as a joke (I’ve hiked several long distance trails more than once). At another hiker get-together a few weeks later, I asked her to hike the GDT with me again. A few weeks later, I got an email from her: “I’ll do it.”

Uh oh, I realized. All this time, I had been jokingly telling others I would hike the GDT, but not actually thinking that I would be able to find someone to come with me. And now, Naomi agreed to be my hiking partner. There was no backing out this time. It would be time to face my fears, get the right equipment, and wish myself good luck.

I was fortunate that Naomi is a very good planner and excellent preparation is one of the best ways to avoid disaster on an outdoor trip. She was able to put together an itinerary and obtain permits. We decided where we wanted to resupply our food rations. Then we figured out a less-than-elegant way of managing the logistics of getting across the US-Canada border.

The morning we started, we took a shuttle to the US-Canada border where the American bus could take us no farther. On foot, we walked to the car immigration area (since there was no pedestrian immigration spot). I stood in the line of cars as rain poured down, my Montbell umbrella serving as protection from the rain as well as making me far more visible in the mist to the cars behind me. Impatient with the ridiculousness of waiting in line with cars—fully knowing that all of the people in cars were protected by the rain from the roofs of their vehicles—I was relieved when an immigration officer called me to the head of the line.

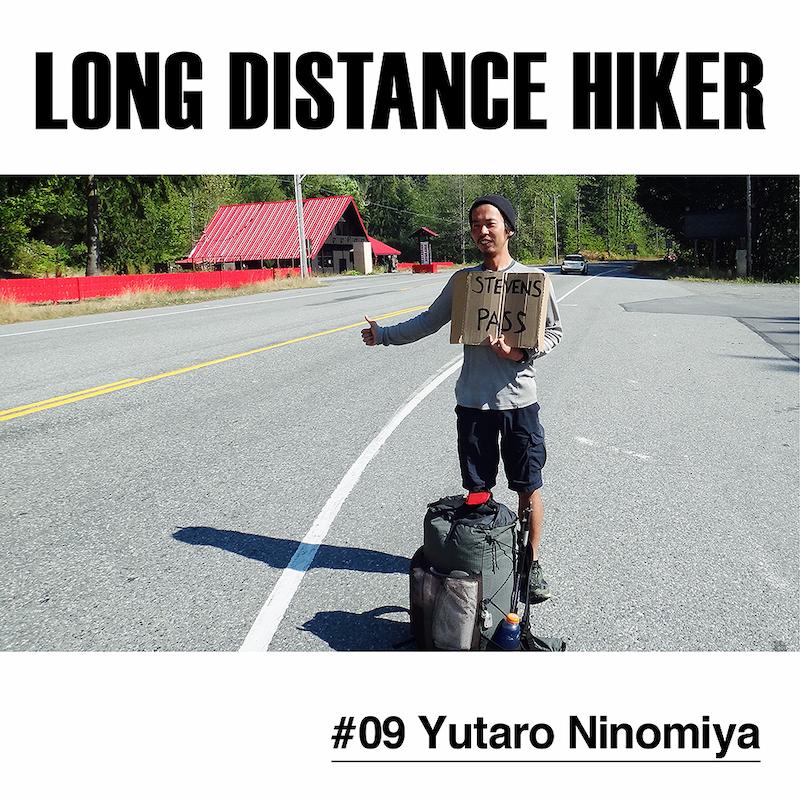

Once across the border, just meters from the agents’ office, Naomi and I put out our thumbs to hitchhike, right next to major road construction. We hadn’t even started the trail yet and already there were a lot of scary things going on here. We were sure that we would be arrested for hitchhiking just outside the immigration office. If that didn’t happen, there was a good chance that one of the giant road construction trucks would not see us by the side of the ride and run us down. And even if we got a ride, there’s always the chance that the driver could be crazy.

Like magic, the second car we saw stopped to pick us up. Inside was a mother and daughter. They both spoke of how they dreamed to one day hike the Appalachian Trail. We had a lot to talk about.

As we started the GDT at Waterton Lakes National Park on a crowded trail, it was hot. I joked that very soon, we would look back on the hot day fondly.

Once we got about 5 km from the trailhead, we had the trail to ourselves. The trail was not always signed, but it was in great condition. The red dirt contrasted to the green hills. The trail had flowers, waterfalls, and lake after lake—a mountain paradise. But the day wasn’t to be free of obstacles. When we popped out at the trailhead, we got lost in a construction area. We searched for what felt like an hour for a flat spot to camp.

That evening, the rain started and it didn’t stop all night. Despite what had looked like good tent placement, we woke in a puddle—and it was still raining.

It took some gumption to pack up in the rain and convince ourselves to hike on. My biggest motivation was the fear that our campsite may have been illegal. Just as we were starting to become accustomed to walking in the rain, we reached a misty cirque covered in dark snow. “I hope we don’t have to go up that,” Naomi said.

“There’s no way,” I said confidently. “The GDT doesn’t take us up and over glaciers and that looks like a glacier to me.”

But as we kept following the trail, it ventured closer and closer to the cirque. As we climbed higher, the rain turned into falling snow. Upon closer inspection, the “glacier” I promised we would never cross was actually a mountainside covered in fresh snow. We couldn’t believe it. Canada is very far north, but it was only August 10th. It was still the peak of summer! This kind of weather did not bode well for the rest of the trip.

We later learned that the rain that happened that day and the rest of that week was quite unusual and even record breaking. For the rest of our journey on the GDT, the locals told us how strangely wet the summer was in the Canadian Rockies and predicted an early fall. We repeatedly disregarded their warnings. “It’s the peak of summer!” we declared, going out of our way to point flower buds that hadn’t bloomed yet, as if they were evidence that there was no way winter could be coming early.

The Great Divide Trail—which more-or-less is in the vicinity of the British Columbia-Alberta border—is called “an extension of the Continental Divide Trail” in the United States by some people. However, the Canadian Rockies are geologically different than the American Rocky Mountains, being comprised of sedimentary rock, mostly shale and limestone (as compared to the American Rockies’ igneous and metamorphic rocks). This means that over time, the Canadian Rockies have flaked off to form impressive, jagged, and steep mountains. These rough and pointy mountains almost always require mountaineering skills and equipment to summit. Furthermore, since the range is so far north, glaciers abound, including the world-famous Columbia Icefield. Although it is hard to get exact numbers, each year no more than 30 people attempt to hike the whole trail.

Nonetheless, the Great Divide Trail brings hikers up close to the intimidating and distinct beauty of the Canadian Continental Divide while sparing its travelers from any technical challenges. While there is much bushwhacking and cross-country travel up steep shale slopes, the trail keeps a healthy distance from glaciers, snowfields, or rock climbing.

Tourists from around the world travel to Canada to see the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks: Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, Yoho, and Waterton Lakes. The GDT allows the hiker to connect all of these parks on foot and to travel to the forgotten corners of the park where even the rangers don’t travel.

After the August snowstorm in Waterton Lakes National Park, we had been warned about a long, strenuous, cross country ridge traverse on shale. Yet, it seemed to go by quickly and never be terribly difficult. That is, until we were within sight of its end: a distinctive col to the east of La Coulette Peak. There was only 1 km between us and easy hiking. The only thing blocking us was a steep slope with thick vegetation and numerous small cliffs.

Our guidebook told us to “follow the animal trails” but it was such slow going that not even an animal would want to come here. We scrambled and bushwhacked up and down the slope looking for the fabled “trail.” Seeing that the lower route cliffed out, I scrambled up a steep rocky area. Soon, Naomi found herself cliffed out below. Her only option to get up to me was a rocky cliff that required a little bushwhacking to get to. As she approached a short rock face, from above, I watched a boulder as large as her torso break loose towards her.

She let out a cry and all I could think of was how bad this situation was. I envisioned her bloodied body. I imagined myself having to tell her husband about the accident.

The rock ricocheted off her leg and fell down the slope. As she screamed back, “I’m ok!” I let out a sigh of relief. We learned an important lesson that day: Canadian rock is not to be trusted.

Waterton Lakes National Park is the only Canadian Rocky Mountain parks not connected to the other national parks along at least one of its boundaries. A series of ATV roads separated Waterton from the other parks. This area was far from pristine wilderness filled with loud vehicle and camps of RVs (whose drivers, admittedly, like the stereotypical Canadian, were quite kind).

We emerged from a muddied, road-turned-to-stream forested area onto a wide logging road. For as far as we could see north of us, the mountainside was completely cleared of trees. It was as if a merciless god had come from above to remove every living being from the land. The landscape was scarred. But it wasn’t a wind storm or spirit that caused this. We had walked into a huge clear-cut. I have never seen anything like it before. It was troubling to see the massive ability of humans to change the landscape.

The next morning, we crossed into an equally disturbing area: an expansive coal blasting mine. From a high point across the valley, the mine area looked like Mordor. Again, it was stripped of trees and the land was blackened. This is the only area of the GDT where hikers must be careful not to venture onto private property. Many hikers before us had been detained by the mine’s many security officials. We moved quickly through the area, paying attention to our maps lest we meet a similar fate.

Despite how disturbing the clear-cut and mining area were, I am glad to have seen them. What I saw is what happens to mountains that are not protected. As an advocate for wilderness protection, I will keep the memory of those scars on the land.

After what seemed like days of easy and not terribly stimulating road walking, Naomi and I would get deep in conversation about anything and everything. It’s at these times—deep in conversation—that we forget to pay attention to the difficulties of our hike: where we were, how much water we had left, or whether we weren’t the only large mammals in the area.

As our road faded away into overgrown bushes and a thin path, we were happily chatting away without a care in the world. We turned a corner and I looked up. The smile—fresh from laughter in our conservation—immediately faded. Thirty meters ahead of me was a grizzly bear foraging for berries. I stopped in my tracks. My legs were shaking. Without thinking, we both reached for our bear spray and spoke loudly and calmly to the forest resident we had disturbed.

Naomi and I have both had grizzly bear encounters before the GDT and neither of them were great. When I thru-hiked the Continental Divide Trail, I had a grizzly come towards me to defend its food source, a rotting carcass it had found. When she thru-hiked the CDT, Naomi ran into a momma bear and her cub, and then heard two bears fighting in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, home to one of the densest populations of grizzlies in the U.S.

This grizzly encounter was different, though. In fact, it became what I call the “ideal” grizzly encounter. The bear heard us and spotted us. I can only imagine if bears could talk, it would have said, “Oh bother. Humans. I guess I need to get enough out of the way that they don’t think I’ll bother them. That’s annoying. I had just found this really great berry patch.”

After the bear crossed a creek and went upslope, we continued on, veins still pumped full of adrenaline. At Tornado Pass, the road faded away and views opened up to the sprawling rocky mountains all around us. Ahead was what our guidebook called the “most difficult” climb of the trip: Tornado Col. It required bushwhacking to treeline and then climbing a steep shale climb better suited for a mountain sheep or goat. The reward was the views. But the real prize was that on the other side of the col was nearly 100 km of blazed singletrack trail.

For the next few days, we had pristine above-treeline views on generally good trail. We saw where storms had washed away bridges, twisted metal signs, and taken out roads. No roads meant there were no other humans where we were—only bear, wolf, and cougar prints.

The most memorable hiking adventures are the ones that help you get over your fears. Not even a week into my trip, I had managed to overcome a fear of grizzlies and navigate some tricky terrain. Yet, by this point, a quarter-way into the trail, I knew I still had a long way to go and more to learn from the GDT. There were bigger mountains to face, glacial rivers to ford, and challenges that would make what I had done so far appear puny by comparison.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

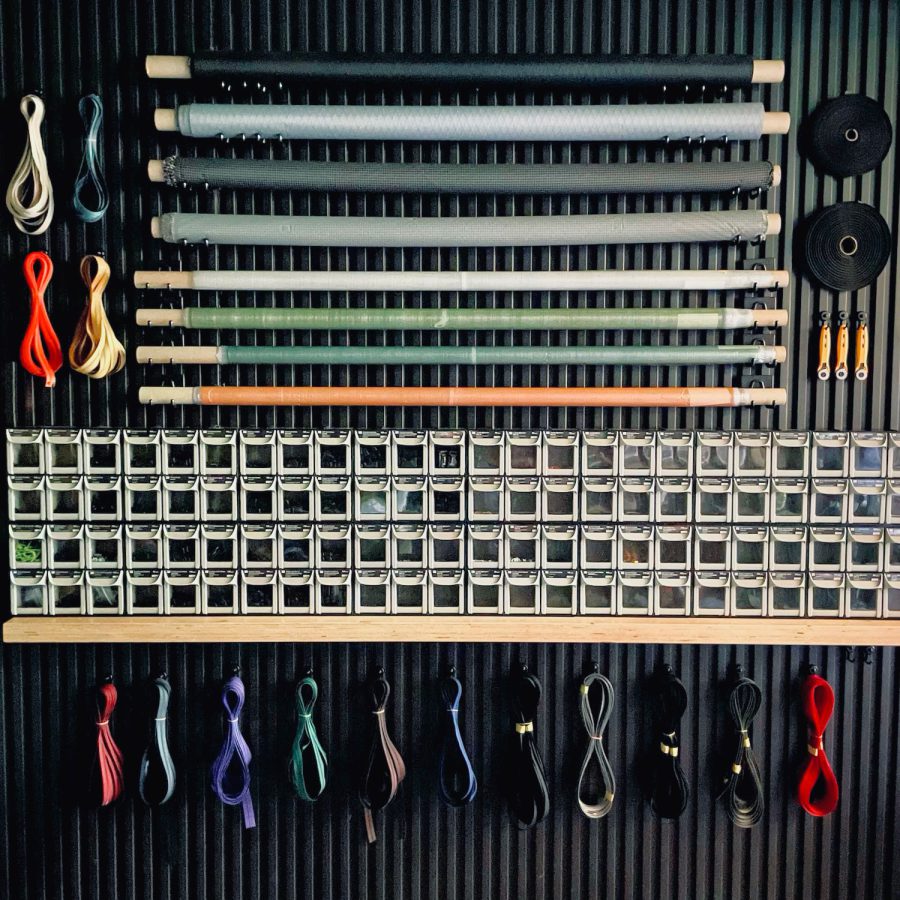

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…