リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#10 / グレート・ディバイド・トレイル(その2)

My friend Shawn Forry, adventurer/hiking partner of TRAILS ambassador Justin Lichter, once said that the true definition of adventure is when you leave on a trip not sure if you are going to make it back—or at least not sure that you won’t quit or get injured before you finish. You grow the most from trails that push your limits. These are the trips that ultimately show you that your limits have fewer bounds than you realized. For me, traversing the Canadian Rockies on the Great Divide Trail was just that.

One thing I’ve learned about established hiking routes is that the route “inventors” design trails to go to certain areas for a reason. Often that reason is because—at least at one point—there were trails in the area. But, through time and neglect, the local vegetation may have had its way with the trail. Sections become overgrown and indistinguishable from the forest or grasslands around it. That’s what my hiking partner, Naomi, and I found in the Bee Hive Natural Area, where there was often good trail that crossed right below the peaks on picturesque high meadows, only to disappear, reappear, and disappear again like a less-than-reliable friend.

One such area was the aptly named Lost Creek, which crosses a network of roads. But flash floods and landslides had taken out the trees, signs, and even metal bridges. All that was left was the damage and devastation. We hopped over dead trees and piles of rocks moved by the deluge. But then, away from the waterway, the trail became clear and well-marked. Nature is harsh on trails. Walking through these areas made me appreciate that every trail exists because a human—or maybe even a few humans on their horses—cared for it.

After some beautiful trail up to Fording River Pass, an hour of getting lost, and then regaining the trail, we reached yet another area devastated by flooding. The trail itself had tumbled into the river and I climbed roots dangling over the water to stay on the steep banks. We hit a dirt road walk—which somehow still had a river going across it—and met many ATVers, and even a couple from New Zealand who were biking from the Prudhoe Bay in Alaska to the southernmost tip of Chile. All was well until rain pelted us, not letting up for hours.

A year before, a friend of mine had hiked the GDT and posted photos of fossilized coral reefs atop this deeply inland mountain area. These fossils are ancient artifacts of shallow seas in the area during the pre-Cambrian era, 515 million years ago. As the Rocky Mountains grew 55 million years ago, they pushed up the old fossils embedded in the old ocean floor. These photos sparked my curiosity about the GDT and made me want to hike this trail, despite my fear of it. If there was one alternate on the GDT I wanted to do more than anything, it was Coral Pass.

But to reach Coral Pass, we had to ford Elk River. With all the incessant rain, we knew the river would be flowing strong. Worse yet, all of the trip notes we could collect from others who had hiked the GDT warned us that all the rocks and plants on Coral Pass would be dangerous to walk on if it was wet. As we continued to get pounded with rain, our fingers numb from the cold, Naomi and I made one of the saddest decisions in the trip: we chose not to take the alternate route up to Coral Pass. Instead, we stuck to the straight forward roadwalk to Elk Lakes Provincial Park.

There was a small consolation prize in sticking to the roadwalk, though. So far on this trip, we didn’t listen to headphones to keep all our senses alert to grizzly bear noises. But, a roadwalk seemed like a safe time to hike to some music. Tunes and podcasts were the saving grace of the next few cold, wet, hours.

A mistake I often make while backpacking is to not eat enough when it is raining. Since I stay warm by moving, I worry that I will become hypothermic if I stop to get out a snack or sit down and eat. Right as my hunger was kicking in, a portly man on an ATV dressed from head to toe in a rubber rain suit stopped to talk to us, unbothered by the rain. His vehicle had no roof and we couldn’t help but feel even sorrier for him than we felt for ourselves—the ATV was moving a lot faster than 5 km per hour and the splashback from the rain looked like a bucket of ice in his face. Yet, he remained jolly. He even gave us a nugget of locals’ advice: just 4 k ahead was an open cabin where we could take a break from the rain.

The 4 km seemed to take forever, but the shabby, dark cabin was heaven when we found it. As soon as we stepped in, the temperature inside was 10 degrees warmer. We dried our gear on the covered porch and made hot ramen while observing the copious graffiti on the cabin’s walls—mostly from long distance cyclists. One note warned: “Saw grizzly chasing a mama moose and her calf in the field across from the cabin.” Ok, we decided. No more headphones.

As someone who always tries to abide by the rules, one of the biggest stresses of the GDT was staying in legal campsites. Because the GDT so often is in National Parks, hikers are required to stay in established campsites and get permits for those sites. That is very different than how many national parks in the US are run. In fact, most of the public land in the US does not require permits or staying at established campsites at all.

As Naomi and I headed into Elk Lakes Provincial Park, we didn’t know where we would camp because we didn’t have a permit for any of the campsites. We were equally worried that because we would reach the road late in the day, all the camping spots along the road would be taken by car campers. All of this worry made the trip stressful.

Much of the GDT is quite remote, so before we started hiking, Naomi and I sent packages of food to the nearest outposts of civilization that would accept mail. In this case, our food was at the Visitor Centre in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park. But when we reached the trailhead and road at 6 pm, we knew there was no way that the centre—still 10 km by road away from us—was still open. We wouldn’t be able to pick up our package! We stuck out our thumbs, hoping at least to hitchhike to a restaurant or store and maybe inquire about whether any of the campgrounds had room for a few backpackers. Miraculously, we were picked up a friendly couple from Ottawa headed to the camp store to get ice. They even let us stay in their campsite.

Surprisingly, the campground was fairly empty. We were in the campsite closest to a trail marked off in red tape with warning signs all around. Many of the trails throughout this area—including the one trail that went to the Visitor Center—looked like a murder scene cordoned off by the cops. Bear activity was very high this year. Many visitors had cancelled their camping trips or family vacations because of it. But we were just happy to have somewhere legal to sleep at night.

The next morning, we walked the road to the Visitor Center (the trail was closed off due to bears). It was a modern wooden architectural lodge, with large windows angled for views, a sunny porch, and leather couches. This is exactly the kind of place that typically does not look kindly upon thru-hikers. Yet, the rangers happily handed over our package and enthusiastically responded to our request to sit on those expensive leather couches and open our food box.

Although the Visitor Center was so remote there was no phone reception, we got permission to use the WiFi to check on the news from the last week. As I repackaged my Alpine Aires, Naomi listened to a voicemail that made her panic: someone had stolen her and her husband’s credit card numbers. Naomi spent the next four hours on phone calls with her husband (who was also hiking a different long trail at the time), trying to sort out the financial mess. At one point, a ranger told us that a grizzly bear was behind the Visitor Center feeding on berries. While all the other tourists grabbed binoculars, Naomi ordered a new credit card.

We snagged a ride back to the trailhead with two young men, one of whom worked on the Haig Glacier nearby at a year-round ski training camp. We learned that he once was one of the top-ranked cross country skiers in Canada. These guys understood the difficulty of our trip—which is one reason that when they saw us hitchhiking on the road, they made a U-turn to pick us up.

Peter Lougheed Provincial Park is one of the most beautiful parks I’ve been to anywhere in the world. In the words of another GDT hiker, “With provincial parks this nice, who needs national parks?” The 5 km loop around the lake is going on my Top Dayhikes in the World list. We continued on pristine trail to the Turbine—a small creek that disappears into a deep limestone canyon within 100 m. It was one of the most remarkable natural features I’ve seen in the backcountry. Surprisingly, it had no guard railing or fence preventing daring travelers from walking to the edge for a photo.

Anywhere else in the world, the views we had from North Kananaskis Pass would have been marred by other humans, yet we were alone that evening, staring at a blue lake and the impressive glacier on Mt. Beatty. Even with rumbling stomachs and the wind beating against our faces, it was the peaceful kind of place that sums up why I hike.

Almost as soon as we crossed the pass and dropped into British Columbia, the quality of our trail changed into rough, steep, overgrown, and then nonexistent. A cliff towered above us and we could hear water roaring—a sign of a nearby ford rumored to be difficult to cross. Dropping from North Kananaskis Pass, Naomi tripped on a rock. As we bushwhacked and attempted to navigate the loose shale, an ominous air came about us.

The sun was setting. There was nothing even close to a flat spot to camp nearby. Our notes from other hikers warned that a large grizzly lived in the area. At twilight, we dropped below treeline into a dark, dense forest, which made searching for trail tread even trickier. We walked over blowdowns, desperately hoping for a campsite. Instead, we found the largest, freshest grizzly scat either of us had ever seen. We quickened our pace.

Upon reaching LeRoy Creek, we were faced with a decision: should we camp on this side and ford in the morning or should we ford and hope to find a campsite in the dark on the other side? The campsites on this side were level, but rocky and bumpy. But knowing the creek water levels would be lower in the morning, we opted to save the ford until tomorrow.

Our campsite that night may have won awards for the worst campsite ever. We slept upon a bunch of river rocks, our tent stakes precariously wedged between them. If the wind picked up or rain come through, our tent would topple. My long Neoair pads were thick enough to cushion the rocks for me, but Naomi had a torso-length pad.

We normally prefer to eat and cook our food far from where we camp to avoid attracting grizzlies to our tent. Tonight—knowing the large grizzly was nearby—we opted to not eat at all. Hungry, grumpy, and sleeping on rocks, we wondered what was on the other side of the ford and the challenges that lay ahead.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

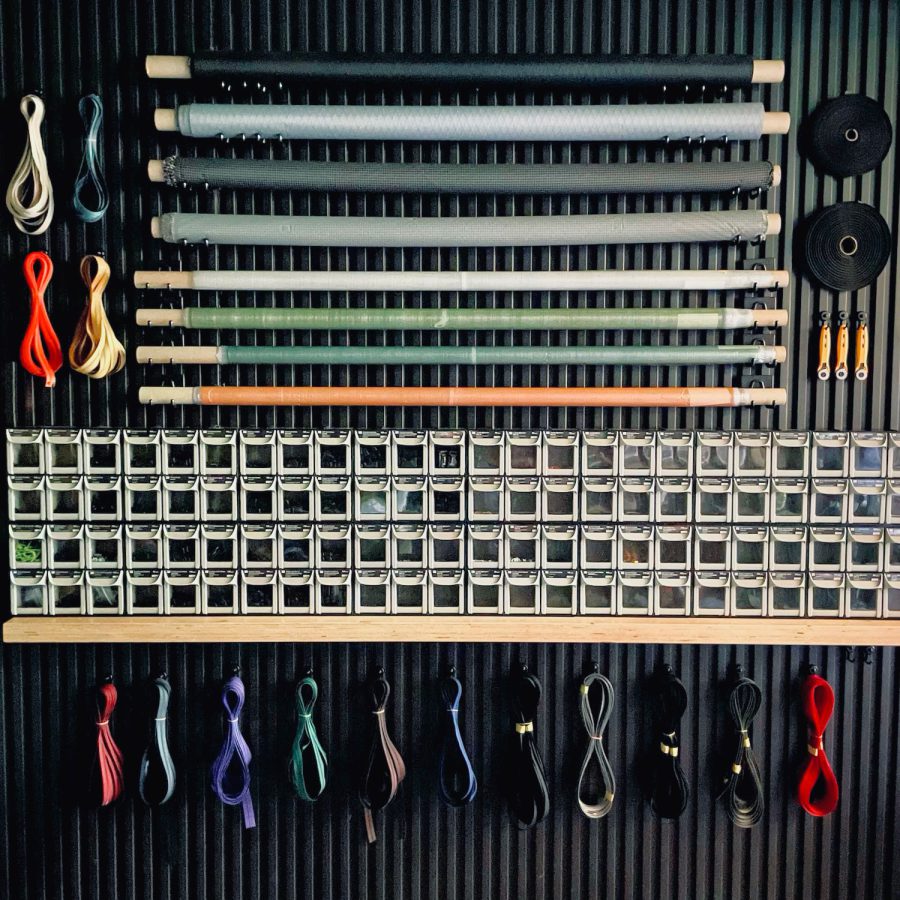

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…

ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…  ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…

ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…  ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…

ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…  ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…

ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…  ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…

ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…  ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…

ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…  ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…

ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…  ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …

ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …