リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#11 / グレート・ディバイド・トレイル(その3)

After an unsatisfying night of sleep on rough rocks, we woke to a miracle: our shoddily placed tent still was standing. A stake had loosened itself somewhat, but there was still a roof above us. I volunteered for the scary task: to go up the hill just out of sight where our food was tied to a tree inside of an Ursack bear proof bag. After the fresh giant grizzly scat we saw less than 1 km away the night before, we were both sure that a big bear resided in the area. I fully expected to find that bear guarding our food bags. Silently, I hoped that I tied my knots strong enough to keep the Ursack attached to the tree.

Relief washed over me when I found neither bear nor evidence that the bear had visited our grub. “Our food is safe!” I called to Naomi, as she tore down the less-than-stable tent. We packed up quickly and contemplated crossing the creek that had stalled us in the darkness of evening.

Overnight, the water levels of LeRoy Creek had dropped. We forded with ease, laughing at how we had tricked the creek by waiting to ford until morning. But we knew soon we’d be crossing Palliser River, which the guidebook discussed as potentially quite dangerous.

We continued on overgrown trail. Years of backpacking has given us an eye for finding the smallest evidence that a trail once existed under the vegetation—a super power that experienced backpackers take for granted, but a skill that baffles and impresses newer backpackers. It was slow going and we constantly checked our maps to make sure we were on course. A very large cairn indicated an intersection with a better defined trail. We were tempted to take it over our ill-defined path, but our maps showed the good trail went in the wrong direction.

The fear-inducing Palliser River was disappointingly low. I found a small evergreen that had fallen over the river, which was now a 3 m wide creek. I didn’t even get my shoes wet. But the waist-high grasses in the meadows we crossed were covered in dew. My skirt and leggings became soaked. Worst yet, hidden amongst the tall grasses were large boulders. When moving through the meadows, we would trip over these obscured obstacles. Other hikers had warned us of ankle-twisting rocks concealed among the grasses.

For a backpacker, twisting an ankle is the some ways the worst injury. It’s bad enough it can make a hiker quit. But it isn’t bad enough that it gets much sympathy. If a hiker falls from a cliff and has to be helicoptered out—now that’s a trail-ending story that you can tell around a campfire. But when a hiker doesn’t see a rock and stumbles, it’s neither glorious nor worth repeating.

We climbed steep trail towards Palliser Pass, excited to take our first steps in the world famous Banff National Park. Our minds swirled with classic images of Banff. As very late season northbound hikers, we had so many people tell us that we were too late to finish. We were told by trail angels that we should have headed southbound instead and that “southbounders were coming any day now.” Naomi and I made it our goal to get to Banff before we found southbounders. Soon, we could make that goal a reality.

Just below Palliser Pass a cobalt blue lake. “Are those hot springs?” I asked aloud. On cold nights, Naomi and I had been dreaming of hot springs. But the water was cool to the touch. Then, we heard a howl. The lake was almost hanging in a relatively flat area on the slope. The mountains narrowed on either side of us. Below the lake was steep and above the lake was steep. Whatever made that howl was in a bowl with us. In this small partially enclosed area, we were not alone.

The howling continued and got closer. I realized, though I was familiar with the call, that I had never actually heard a wolf howling in real life before. I wasn’t afraid. I didn’t want to stop hearing its song.

The wide Palliser Pass was anti-climactic. There were no grand views of Banff. The trail didn’t become suddenly more distinct, even if we were now in a relatively well-funded park that could afford to pay trail crews for maintenance. We were in a wide meadow. However, at the pass was something I had never seen before: a “Living Trail Register.” Instead of registering our name in a notebook, someone had left behind bits of wood which would biodegrade over time. We saw the names of our friends ahead of us—Not A Chance and Free Bird. Reading their names in this beautiful and atypical register almost made it feel like we were not all alone.

Soon, our trail became overgrown with sharp shrubs and brushes that scratched at our legs. Though we were going downhill, it took us much longer to make 7 miles to the next campsite than we anticipated. The sharp bushes went on forever.

After a break at the Birdwood Creek Campground—which appeared abandoned—we continued towards the main part of Banff. What was weird was that we didn’t see any humans or even signs of humans. We walked past a ranger station which was boarded up for the summer. Certainly we were not so late in the season that the rangers had all gone home? Where were footprints from other hikers? Weren’t we in a national park? Where were all the humans?

We walked through bright, plastic flagging across the trail. There was no sign that said the trail was closed. What was going on?

The closer we came to the Spray Valley trailhead, the more defined the trail became. There were even bridges over the creek. We hit the main trail, the border between Spray Provincial Park and Banff National Park, and saw a sign indicating where we had come from, including a note that Palliser Pass was 16 miles away. Finally, we saw humans walk up the wide, main trail—really more of a fire road that is used occasionally for rangers’ vehicles. The voices of a loud, boisterous group encouraged us.

“We just got our permits,” they told us. “Bear activity has been very high recently. People have been cancelling their reservations. That’s why we were able to get a last minute spot here.” Banff camping permits are notoriously difficult to score.

“We’re just trying to be loud,” another one in the group says. That they certainly were.

We let them go ahead so we could take a snack break. While munching on our bars, we heard a loud sound like a gun shot. Had a ranger shot a problem bear in broad daylight?

It didn’t take long to pass the loud weekend hiker group. They didn’t know what the sound was either. Unlike US National Parks, guns are explicitly prohibited in Canadian National Parks.

When we reached out campsite for the night, we joined another boisterous crew of 6 from Calgary. They confirmed that the rangers had warned them extensively about bears. “They weren’t even giving permits to groups less than 4 people,” they told us. Naomi and I had procured our camping permits months in advance for a party of two. Were our permits no longer valid? It was going to be an interesting night.

We woke early to get in lots of miles, hoping to make the gondola at the Sunshine Village ski area. From there, we would ride down to Banff where we could resupply at grocery stores. Our maps were conflicting: we would either have to hike more than 30 miles or 25 miles today. We also did not know what time the gondola stopped running. But we knew we had to be out of the Park because (due to some mileage miscalculation) we had not made a reservation for a camping permit for the night.

It was magical to see the prime areas of Banff without the crowds. The glaciers hung above the emerald Marvel lakes and it was shocking that such a beautiful place could exist without people wanting to see it at first light. Maybe they were scared by the bears.

We climbed to Wonder Pass and got our first view of the iconic Mt. Assiniboine, which we jokingly called “Mt. Cinnabon” after the cinnamon roll baking company (food was clearly on our mind). At the pass, we spotted our first humans, who came at us in droves from the Assiniboine Lodge and Naiset Cabins—two places where wealthy hikers can helicopter in to the base of Mt. Assiniboine and get the backcountry experience without the walking.

The mountain, with its Matterhorn-like steepness and reflection in Lake Magog, was stunning but the crowds overwhelmed us. After a feeble attempt to change our permits so that we wouldn’t have to hike all the way out to Sunshine Village and an even sadder attempt to score ourselves a hot beverage at the Lodge, we knew we had to continue on. A weather report with snow in the forecast for the next two days confirmed our resolution to hike on.

We walked past the frighteningly low Lake Og where campers were already claiming first-come-first-serve campground spots at 11 am. We needed water, but the lake was so low that, after consulting the map, we were certain there was more water before Citadel Pass. Onwards we went through the Valley of the Rocks, which looked as dry and desolate as the PCT in Southern California. Onwards we went through dry pine forest that reminded us of the PCT in Northern California.

Backpackers who have spent significant time in the desert know that moisture has a smell. Naomi and I became thirstier and thirstier. Our maps indicated that we would cross many streams. In my delusion, I thought we were further along the map than we actually were. Each stream bed we passed held nothing but mud. We smelled water in the air, but found nothing but muck.

Hikers going downhill in the opposite direction of us confirmed the large lake indicated on our map was dry. “There is no water until Sunshine Village” a snobby-sounding older male hiker scolded us. “Never trust a hiker” is an old adage, but the words gave us little hope. Who would have thought we would get this dehydrated on the wet Great Divide Trail in a wet year? What a rookie mistake we were making!

When the trail appeared to flatten out, we found the dry lake. The map indicated two other lakes—much smaller and more likely to be dried up. Feeling deflated, we continued towards them. That’s when I spotted a shallow pond with a 20 cm narrow stream draining into a hole. We rejoiced!

I guzzled water until my belly hurt. We walked over Citadel Pass where the trail even crossed a stream! Why was the snobby old hiker so wrong?

We briefly talked to some 20 year old hikers who told us they had come up on the gondola. “It closes in an hour,” they warned us. We had to hustle. At my top speed, I could make it. But there was a huge hidden pass between us and the gondola. I ran on the flats, my pack rubbing at my shoulders. We had to make that gondola down to Banff. We didn’t have a camping permit for anywhere in the Park—including Sunshine Village. Where would we sleep tonight?

I ran until I hit the dirt fire road down to the gondola. Naomi ran, too. My lungs hurt. And then I saw the cars of the gondola. It was still running! I still ran to the operator. A large clock hung above the entrance to the gondola. It was 5 minutes past the closing time.

“Gondola is closed,” the worker told me callously. I wanted to ask why it was still running if it was closed, but I was so exhausted I could barely speak.

“But the employee bus is headed down to the parking lot,” he reassured me.

Naomi and I walked to the employee building and talked to our friendly bus driver from an Eastern European country. There were only a few employees on the bus and ourselves. The road down the mountain was steep with a big cliff on one side. I have no idea how the bus runs in the winter. Employees got out at the bottom of the gondola at a big parking lot.

Naomi and I looked at each other, crestfallen. This parking lot was 7 miles from the town of Banff itself. We were too exhausted to walk, and this trailhead in the mountains seemed like a poor place to hitchhike.

The bus driver made her colleague promise not to tell their bosses, and she continued to take us all the way to town!

We were deposited in downtown amongst people, cars, and restaurant smells. Hotels ran at $600 a night. We may have been out of the Park, but we still didn’t have a legal place to sleep tonight. I was annoyed and worried that we had pushed so hard to get into Banff only to be stuck with the same problem we had in the Park. But being in town did have one advantage over being the park: we split a four-person family-style dinner between the two of us.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

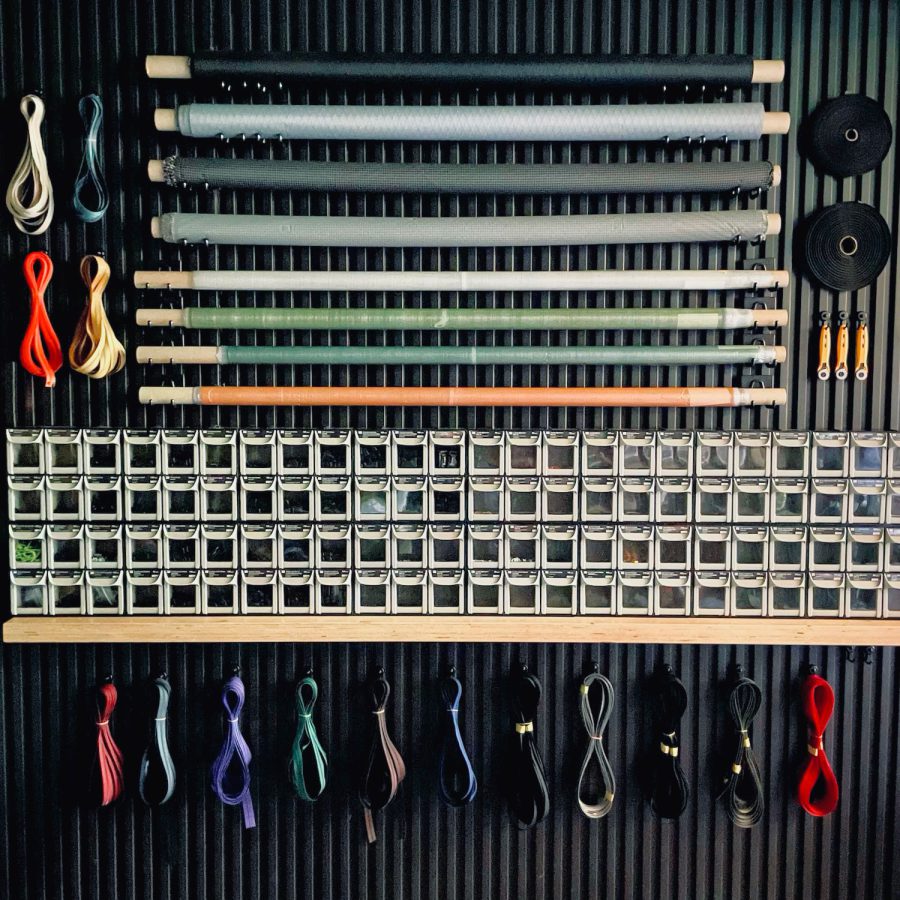

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…

ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…  ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…

ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…  ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…

ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…  ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…

ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…  ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…

ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…  ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…

ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…  ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…

ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…  ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …

ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …