リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#17 / ロング・ディスタンス・ハイキング後の喪失感との向き合い方

How to Cope with the Post-Hike Blues and Re-Entry from a Distance Hike

After hiking their first long trail, many hikers come home and realize how boring “normal” life can be. After days of chasing a grand goal, working in an office can feel unfulfilling. Post-hike depression or post-hike blues is a normal part of the hiking journey, yet is not often talked about in the hiking community. This article is meant to de-mystify the post-hike part of the journey and give hikers tips to cope with re-entry to “normal” society.

Many hikers feel ashamed that they experience post-hike blues. They feel like they are alone—that no one else is sad and missing the trail like they are. But the truth is that post-hike blues happens to almost every distance hiker, especially after their first distance hike.

The post-hike part of your journey can be difficult, but just like the chain on this rock climb, there are some tools that can make it easier.

Like blisters, chances are a hiker will experience the post-hike blues. The more we as the hiking community talk about post-hike blues like we do about blisters, altitude-sickness, and being hungry, the better off we will be.

The more you know about it, the better you can prepare for post-hike blues before and during your hike.

The first step of tackling the post-hike blues is understanding why post-hike blues happens. I have several theories.

Sometimes, it’s difficult to return to a city after spending weeks or months being immersed in the beauty of nature.

When we’re on a long hike, we’ve spent weeks if not months immersed in nature. Studies show that spending time in nature can make people feel happier. When a hike ends, suddenly, the amount of nature in your life goes down.

Exercise, too, has been shown to make people feel happier. On a long hike, we are exercising all day, almost everyday. Our brains are rushed with endorphins, which are associated with feelings of euphoria. Ask most long distance hikers about how they enjoyed their trip and euphoria may be a word that use to describe it.

But after a hike ends, it’s almost impossible to get as much exercise as one can on a long distance hike. If you’re lucky enough to come back from your hike with a job lined up, then you’ll often be sitting at a desk for 8-10 hours per day. That’s 8-10 hours that you aren’t exercising. After the brain has been supplied with endorphins that make it happy for so weeks or months, it’s inevitable to feel a “crash” in the weeks or months after a hike ends.

After a long hike, it may seem like the things that make you happiest are the mountains that are so far away. But there’s beauty to be found closer-by, too.

What makes the situation worse is that many distance hikers return from a long trail only to feel like there’s “no point” in dayhiking or that it isn’t worth it. For example, imagine a hike where it takes 2.5 hours to get to a trailhead (meaning 5 hours roundtrip for transportation). If the hike itself is 5 hours long, the hiking to driving ratio is 1:1 for a ten-hour day. Is it worth it? I’ve heard many thru-hikers say that dayhikes don’t feel rewarding enough to justify the expense of time and money associated with transportation to a trailhead. Perhaps before they left for a distance hike, they would have strongly believed the transportation time to hiking time ratio was worth it. But distance hiking changes some hikers’ perspective on this issue.

What makes the post-hike blues even worse is that even if a person finishes a hike and is retired (or isn’t working), the winter comes. Getting outdoors and exercising often become harder for some people during winter. Reduced sunlight during winter can affect people’s mood, too. Blues associated with the loss of nature and the loss of endorphins is compounded by the season.

Another reason that distance hikers feel post-hike blues is the loss of community. On a distance hike like the Pacific Crest Trail or John Muir Trail, hikers often become friends with strangers they meet along the way. The trail and nature becomes a great leveler where we feel more comfortable talking with others. On trail, we have more in common with each other than we do when meeting a stranger on a bus. So it’s much easier to talk to other hikers about conditions on the next section of trail, whether they saw a bear or snake, or how they fared the storm last night.

On a long hike, there’s a strong hiking community. We watch out for each other. If another hiker gets injured or goes missing, we’ll do everything we can to help them—even if they are strangers. Everyone has a shared value of being in nature and experiencing it on foot. The hiking community becomes like family.

But when a hiker returns from a journey, they’re separated from their hiking family. Sure, the internet and social media help hikers stay better connected. But it’s not the same as being around other hikers.

Chances are that your “real” family and friends from back home aren’t interested in hearing about every detail of your hike. Or perhaps they are interested for the first few weeks, but then tire of your hiking stories.

The loss of community—and of people who want to talk about the journey—can be devastating to many hikers.

What makes the loss of community even more troubling, though, is it is associated with a loss of identity. On trail, we identify as hikers. Or thru-hikers. Or ultralight hikers. Or solo, female hikers. Or hikers from Japan. No matter how we may have identified ourselves on trail, that identity means almost nothing in the “real world.” Back in the office, few people care that your pack is ultralight, even if that was something you were very proud of just a few months ago.

Navigating through life post-hike can sometimes be trickier than the long hike itself.

Post-hike blues can be exacerbated by other stresses associated with re-entry. Some hikers return from the trail without a job or without housing. Financial and housing-related stresses can make it even trickier to cope with the post-hike blues.

If a hiker doesn’t have a job, that hiker may have nothing to do. This is in stark contrast to life on the trail, where that hiker always knew what they had to do: keep going towards Canada or Mexico to wherever the end point of their trail may be. On trail, we have a clear goal in life for so many months—and each day we have the satisfaction of knowing we are doing everything we can to get closer and closer to that goal. But in real life, some people may feel like they don’t have a goal. Or even if they have a goal, there are less tangible signs that we are getting closer to it.

Reflecting on personal accomplishments and being strategic about how you plan to live your life after a long hike can help with post-hike blues.

So what can a hiker do to mentally and financially control post-hike depression? How a hiker deals with re-entry often is related to how they left things at home before they went on their hike.

First, financial, housing, and relationship instability makes re-entry to the “real world” much worse. Many hikers do financial planning before they leave for a trip and allocate enough funds to last for several months after their hike. Before you leave for a hike, do everything you can to ensure you have a stable, happy place to call home. If your boss is willing, you may benefit from having a job lined up for after you finish your hike. Or if a reason that you are going on a long hike is because you don’t like your job or boss, you may be less stressed knowing you won’t have to return to an unhappy workplace.

Just like on trail, having a goal of where you want to go makes choosing what to do in difficult situations easier.

For many hikers, post-hike blues is exacerbated by relationship issues. Before you leave home, communicate clearly with your family and friends about what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and how you will stay in touch during your trip. Use your hike as a way to bolster your relationships, not to isolate yourself. Many distance hikers have returned from their journey only to have their spouse leave them (or to leave a spouse). For those hikers, divorce and separation can be worse than any post-hike blues.

When you return from your hike, keeping up with some type of exercise routine can soften the blow of the post-hike blues. While most hikers claim that all they want to do is hike, other hikers find that the return to society can be a trigger to take up a new sport or physical activity. Since hikers often return to “real life” in the late fall or winter, this could be a time to take up an indoor activity.

This activity need not be as vigorous as hiking. It could be ping pong or dancing classes. What matters is that you are physically moving, around other people (“your community”), and that you are leaving your home and work place (going somewhere else) to do it.

After I hiked the Continental Divide Trail, I started going to yoga classes for the first time. The daily routine helped me cope with returning to the city from the wild, open mountains of the Continental Divide. The yoga classes were indoor and heated, so I could never use “bad weather” or “too far away” as excuses to not exercise. The stretching helped me heal muscles and tendons that had become stressed from overuse during my hike.

With any exercise goal, the best way to keep up with it consistently is to turn it into a routine. It’s much easier to exercise each day if it becomes a habit. With habits, you don’t need to explain it to yourself or others. Exercising every day is just what you do and part of who you are.

Sharing your hiking stories with other hikers can be a way of giving back to the greater hiking community. Photo by John Carr

An important aspect of going to exercise classes is building community. When we return to society, we are no longer around our hiking friends. No one is ever going to replace your hiking friends—they’re special people who understand you. But many hikers find that having a group of people they do a physical activity with can mimic the community they had while hiking and make coping with post-hike blues easier.

Attending hiker gatherings can be a way to keep in touch with the hiking community when you are on not on trail. Photo courtesy ALDHA-West by John Carr

If you’re lucky enough to live near other people who have distance hiked, staying in touch with them can help with the post-hike blues. Many hikers in Portland, Oregon hold potlucks, parties, and get-togethers throughout the winter. At these events, veteran hikers swap trail stories and tips for new adventures. TRAILS Cultural Magazine holds a Long Distance Hiker’s Day where experienced distance hikers can get together and share stories and also teach new hikers.

During the summer when you are on your thru-hike, you can start building your post-hike community by collecting contact information for hikers you meet who live in your area.

The friendships formed on trail can last a lifetime. Staying in touch with trail friends after your hike can make the transition to city-life easier.Photo by Kate Hoch

When I was hiking the Tahoe Rim Trail, I met a Pacific Crest Trail hiker named Twinkle. We discovered that we both lived in Denver. Twinkle is a “planning type” of person. He realized when we both returned from our hikes, we would want to spend time with other hikers. I swapped phone numbers and emails with Twinkle. That fall, I got an email from him. Twinkle had collected contact information from all the hikers who live in Denver that he met while hiking the PCT. We used his contact list to develop a hiker group in Denver. We would get together at restaurants to talk about hiking or go on dayhikes together. Some of the hikers in that group have become my best friends—even though I met them in a city and not on the trail!

Sharing your knowledge of the trails with other hikers is a key aspect of dealing with post-hike blues. Volunteering and caring for people other than yourself takes the mind off its sadness. No one learns how to hike a long trail by themselves. By mentoring other hikers, you are making it possible for them to have a better on-trail experience.

Sharing your hiking stories with children can be a way of giving back.

Similarly, hikers often find themselves happier when showing gratitude for the time they had during their adventure. Giving back to the trail organizations like the Pacific Crest Trail Association, who maintains the PCT, can be one way to show gratitude. Similarly, I show gratitude by writing thank you cards to the trail angels who helped me on the journey. When you meet trail angels, you can prepare to show gratitude to them by asking for their contact information or mailing address. Some hikers even send trail angels thank you postcards as they journey up the trail.

Planning for a long hiking trip requires some reflection on what life will be like after your hike, too.

Lastly, hikers can beat post-hike depression by having something to look forward to. Hope is a way out of sadness. Plan for another distance hike. Studies show people are happiest when planning for a trip. Even if you don’t know when or how you’ll be able to go on another distance hike, just the planning can soften the post-hike blues.

Related Articles

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#15 / 日本人ハイカーはどう思われてる?<後編>トレイルエンジェルの視点

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#15 / 日本人ハイカーはどう思われてる?<前編>アメリカ人ハイカーとPCTAの視点

『LONG DISTANCE HIKERS DAY 2019』開催! – 2月16日(土) /2月17(日)

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

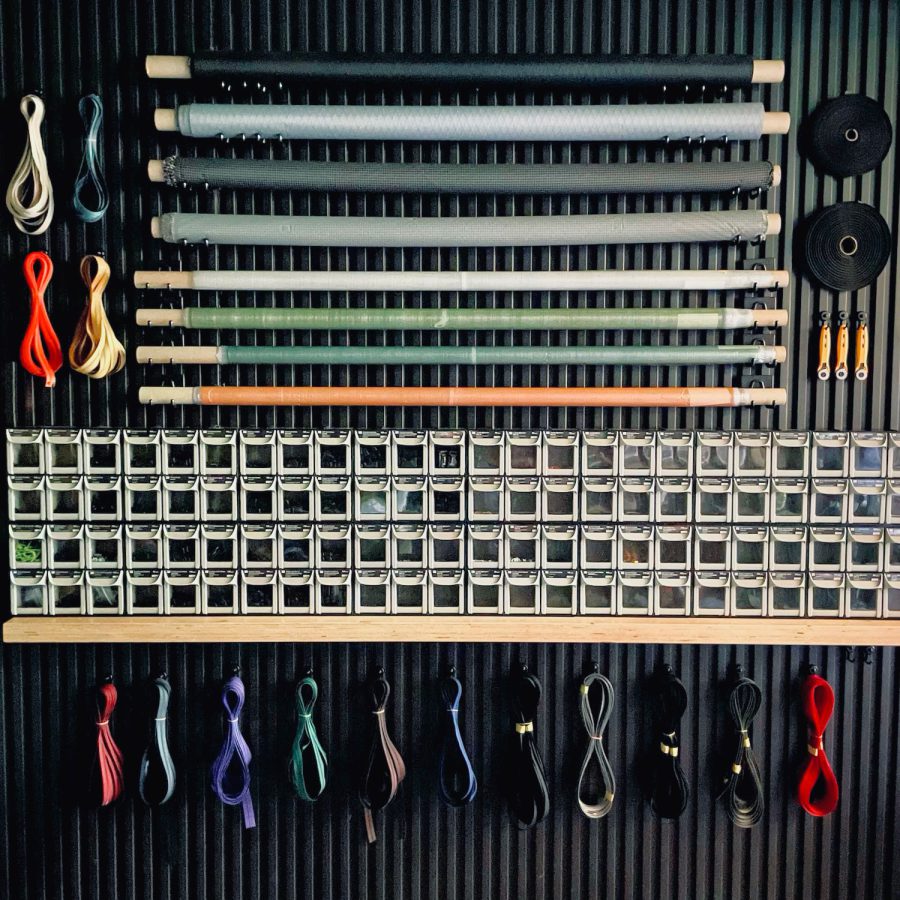

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…