Crossing The Himalayas #1 / トラウマの大ヒマラヤ山脈横断記#1

Crossing The Himalayas – Nepal Article #1 By Justin “Trauma” Lichter

In March of 2011, my climbing partner, Shawn Forry (aka Pepper), and I, set off to hike the length of the Himalayas from the easternmost 8000 meter peak in the world, Kanchenjunga, to the westernmost 8000 meter peak, Nanga Parbat. The distance of the hike was between 1900 and 2600 miles. It’s difficult to be precise since we knew our measured distances on the maps were 20 to 30 percent short of actual miles due to the differences in map scales as well as their inaccuracies.

Every time I go on an expedition, people ask the questions, “Why did you do it?” or “Why did you go there?” The answer is simple. I want to see new places, explore new areas, and challenge myself in different conditions. The locations of my expeditions change, but the reasons don’t. This time, I chose the Himalayas.

Part of the fun of a hike is the challenge of the planning. It helps get me excited about the trip. I get to play with maps of different scales and try to weave them together like a jigsaw puzzle. The goal is always to connect as much backcountry area, big mountains, deep river valleys, and anything relatively unpopulated, with the least amount of walking on roads. Sometimes this works like a charm and other times it leaves you disgruntled and hating life as you plod along on hot asphalt with cars whizzing by for what seems like an eternity. Never the less, knowing that my route was great or needed some tweaks and then dealing with everything that entails, makes the trip that much more rewarding.

There wasn’t much information out about a route through the Himalayas when we undertook this project. Robin Boustead, a native Australian who is living in Kathmandu, is trying to put together a Great Himalaya Trail through the Himalayas and has published a guidebook on many other treks in Nepal. We got some information from him, but at the time, he had only hiked the Nepal section of the route we were planning. We gathered the information he had for that section and bought some maps for planning the rest of the trek.

India and Pakistan are relatively unknown. We used websites, Lonely Planet hiking books, road maps, and anything else we could find. In a few cases we even read historical biographies about old British and Kiwi explorers heading into the Himalayas. As could be expected about largely unexplored territory, the information we collected from different sources often didn’t jive. We were getting mixed signals about a lot of the passes regarding how technical they were and what equipment we might need for crossing them. In the end, we tried to foresee as many unforeseen circumstances as possible and decided to plan for resupplies and extra equipment, since we knew we wouldn’t be able to get much gear once we were there. We devised a plan to leave our extra kit for swapping out gear and resupplying in a duffel bag at a hotel in Kathmandu which was reachable from a couple of access points on the hike.

My climbing partner, Pepper, and I have a different mindset than most people heading into the Himalayas. We come from a long distance hiking and ultralight background compared to a mountaineering or trekking background. We were doing this trip with as little as we could get away with and were trying to use gear items for multiple purposes. We spent a lot of time planning our gear; figuring out how we could shave ounces and then hoping that our ultralight equipment would work in the biggest mountains in the world.

We knew the weather window was tiny for a trip of this magnitude. There are basically 2-3 months in the spring and 2-3 months in the fall before the onslaught of monsoonal moisture or impending winter weather. The monsoons move into Nepal by June and then sweep from east to west into India. We were going to have to maximize our time on the trail and move fast to keep ahead of them and to finish in one season. No names come to mind of people who had finished in one season before us, but if anybody could do it we knew it was us because of our ultralight backgrounds and our tendency to hike over 30 miles per day.

The actual preparation for this trip was quite different than a lot of the others that I have embarked on. It was a whirlwind. I left the United States on March 21, which was a little early for me since I typically work as a ski patroller through the winter. I was on patrol up until the last week, training for the hike by skiing (nordic, backcountry, and telemark). The fact that it was a record setting winter which blasted the region with 2-3 weeks of straight snow around the time we were leaving, didn’t really help. It was a nightmare. Everything took so much longer to get ready and get around. My driveway hadn’t been plowed for over a week due to the 15 feet of snow that had dumped on us. The plows simply couldn’t keep up. My car couldn’t even make it up the driveway so just getting the duffel bags to the car and getting out to sort out any last minute errands was an adventure. I wasn’t sure if I was even going to make it to the airport.

I stepped off the plane in Kathmandu and was a combination of relaxed, nervous, and excited. It was great to put the madness of pre-trip details behind me but now I had to deal with the mayhem of Kathmandu. I loathe the onslaught of touts and taxi drivers that most second and third world countries have when you exit the airport. I assume everybody is trying to rip me off but despite my dread, I mentally prepared myself and was ready for it as I exited with my two huge, heavy duffel bags. After the usual negotiations, I finally agreed on a price and got a ride into Thamel, the tourist district of Kathmandu. We still needed to pick up maps, get permits, and scout out resupply options before we set out on the hike.

Thamel was intimidating. It’s a spider web of interlacing, tiny streets with no rhyme or reason; all filled with a million people wandering in and out, while cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and scooters weave between them. It was sensory overload and it smelled foul. I will never forget the putrid smell of the rotting garbage on the streets of Thamel.

Pepper was due to arrive the next afternoon. That did not go as planned. He didn’t double-check his ticket and assumed his flight left at 12 noon when it was actually 12 midnight. He missed his flight and was rescheduled for the next day. I wandered through the crowded streets trying to get acquainted with the city while I picked up the maps for the hike and looked for things for our resupply kit. Resupply options weren’t looking promising. I saw street vendors selling days old chicken and meat, the skinned goats and pigs were covered in flies and all of it sat rotting in the sun. By 3:30 in the afternoon, the jet lag from 72 hours of travel from San Francisco to Seoul to Bangkok to Kathmandu, hit me and I was done for the day. The next three days were the same.

We final got out backcountry permits straightened out for the first couple of weeks of the trip and were ready to set off on the hike. Pepper got sick the following day from eating something bad in Kathmandu. He felt better the next day and we were all set to leave the next day, but as is customary in Nepal, the government went on strike and everything was closed and shuttered. This happened at least three more times during the trip. After a day of anticipation we finally caught our flight to eastern Nepal. We’d then have to catch a long bus ride into the mountains since the airport in the mountains was closed for resurfacing. It took us a few weeks to get used to living on Nepali time – things don’t happen on your schedule, or a schedule in general.

- « 前へ

- 4 / 4

- 次へ »

TAGS:

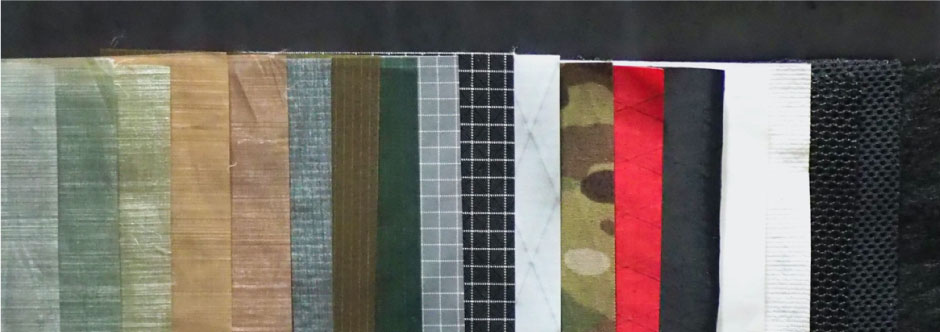

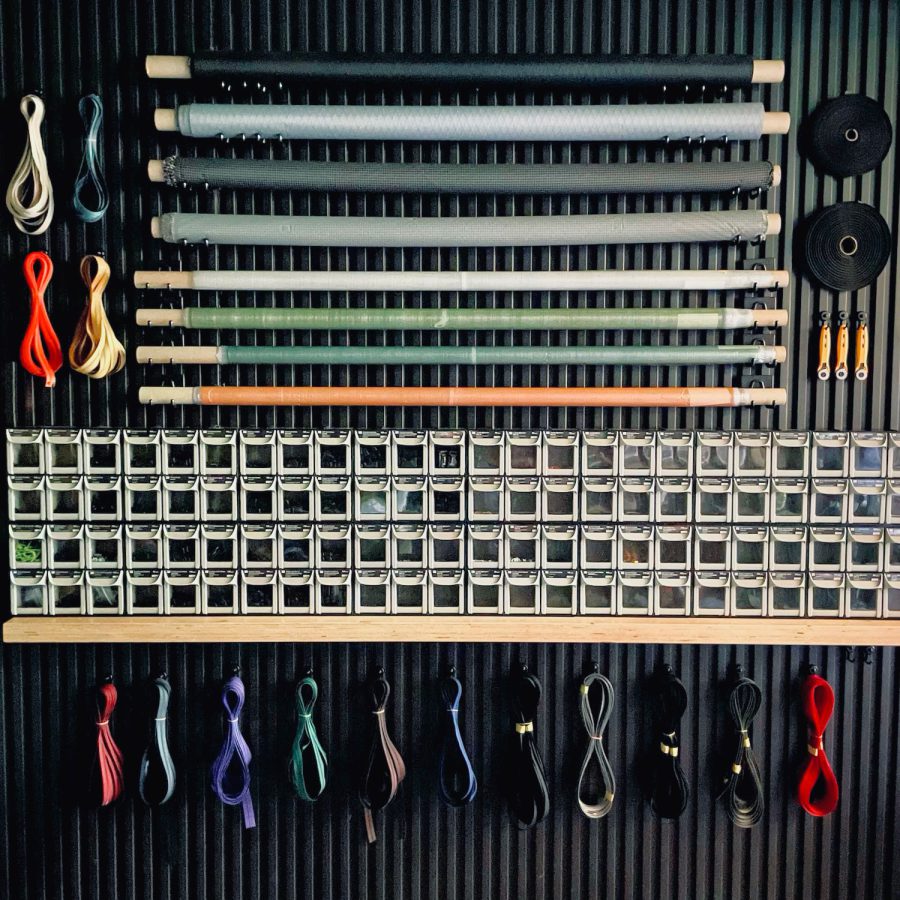

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…