Crossing The Himalayas #7 / トラウマの大ヒマラヤ山脈横断♯7

Crossing The Himalayas – India GHT #2: By Justin “Trauma” Lichter

I ended up roadwalking, connecting local use trails through towns and villages, and connecting areas called forest reserve areas for the first two weeks in India. It definitely wasn’t the highlight of the trip but it was very different from the last couple of months of hiking. I was able to pass through a lot of towns in the foothills and see the cultural side of India along with its economic development.

It was in stark contrast to Nepal. Trekking isn’t a pastime or a big tourist attraction, unless you are in the Leh/Ladakh area of India. I received strange looks everywhere. The Nepalese are open and inviting to travellers as part of their culture. The teahouses were originally set up as stops for travellers where they would be invited into people’s homes. Now on the popular treks this has transitioned into a lodging/hotel situation. Indians were a bit more standoffish generally and weren’t as inviting into their homes for meals or places to sleep.

Also, I wasn’t allowed into the high elevation areas of the mountains since I couldn’t get the permits from the government. Instead I was traversing the range at roughly 3000 meters in elevation. The roads were generally sealed and paved, unlike the roads into the mountains in Nepal, which were usually dirt. India is a growing and expanding economy and they have a mission to connect every town with a road within the next ten years.

It is hard to argue with their economic vibrance and goal from a personal level as it makes people’s lives easier since they have access to roads, cars, and buses. But the entire time I hiked through India this catch-22 resonated in my thoughts. India’s mountainous and wild areas were being bounded and isolated by roads and development. In turn they were ending up with pockets of hiking areas or backcountry locations that were no more than 80 kilometers of hiking before I would typically come to or cross the next road.

Nepal is trying to emulate India’s expanding economy and also put in these roads. However, Nepal does not have the money to successfully and sustainably build roads. We came across numerous dirt roads that had been expanded farther up into the mountains that had washed out within a year or two during the monsoon season. They then did not have the money to repair them. Essentially they would build roads but be unable to maintain them so they became unusable. These thoughts and many more about development versus wilderness and saving wild places versus making people’s lives easier echoed in my mind as I was road walking.

Along with the additional roads was came the ability for locals to get more goods. Many of the villages weren’t farming for sustenance. They also had deliveries of potato chips, soda, and other processed food items from the cities. The small stands were lined with bags and bags of Lay’s potato chips, including Masala flavored potato chips, and even sometimes chocolate and candy bars. It was finally possible to get some high calorie items along the hike.

Other areas along the roads had frequent roadside stands called dhabas. These restaurants often served decent food for a good price. Other places I would be road walking and pick up a quick chai tea from a chai wallah along the roadside. It was so different from any other place I have been.

I am typically very cautious about what I eat in foreign countries, especially second and third world countries. I try to be mindful of any fresh fruit or vegetables that could have been washed in untreated water. I feel this helps to prevent illness and unnecessary time off the trail. When I hike internationally this is an integral part of my strategy and ultimately the success in achieving my goals.

With that being said, India was a great country to eat in for a hiker. Most of the people drink tea, typically sweetened with milk and sugar so it was even tastier for a hiker with a sweet tooth. The tea always seemed to be piping hot and therefore safe to drink. Also most of the meals contained a lot of vegetables but were sautéed or stir-fried. There was hardly raw produce used – a perfect combination for a cautious and health conscious international traveller.

It was interesting for about five days but then the novelty began to wear off. After a few more days of connecting use trails between villages, trails that were short cuts between road sections, and other roads I was ready to be off the roads for a while. Since I was passed the areas where I couldn’t get the permits, I started connecting some more trails through more remote areas. Most of them were pretty decent quality since they were still fairly low in elevation and heavily used by locals. Typically as roads are developed, trail quality deteriorates because the locals start to gravitate towards the roads. People will walk on the roads or have the opportunity to catch a ride, so they cut to the road as soon as they can instead of walking on the trails any longer. There were no foreigners and no locals on most of the rural backcountry trails.

In India most of the locals don’t seek to recreate in the outdoors. It is a place they live and that they travel through, but not a place that draws them to clear their mind or to go camping. Hopefully with the emerging middle class this will become a more common experience, otherwise it is likely that they will not value the outdoors enough to protect it. Along the same lines, that is why it was so difficult for me to find maps and any outdoor equipment or canister stove fuel when I was in Delhi.

I continued on the trek to my next main resupply. In India, unlike in Nepal, I was able to hit larger towns in the mountains, which were well supplied and resupply without flying out to a big city and then headed into the areas that I knew would be the highlight of the Indian section of the Himalaya.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

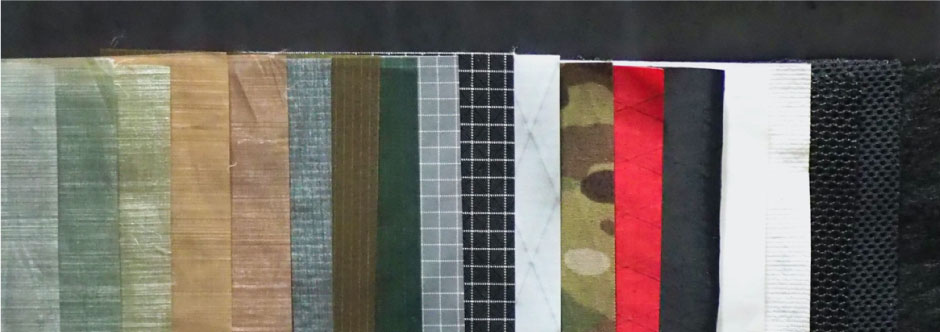

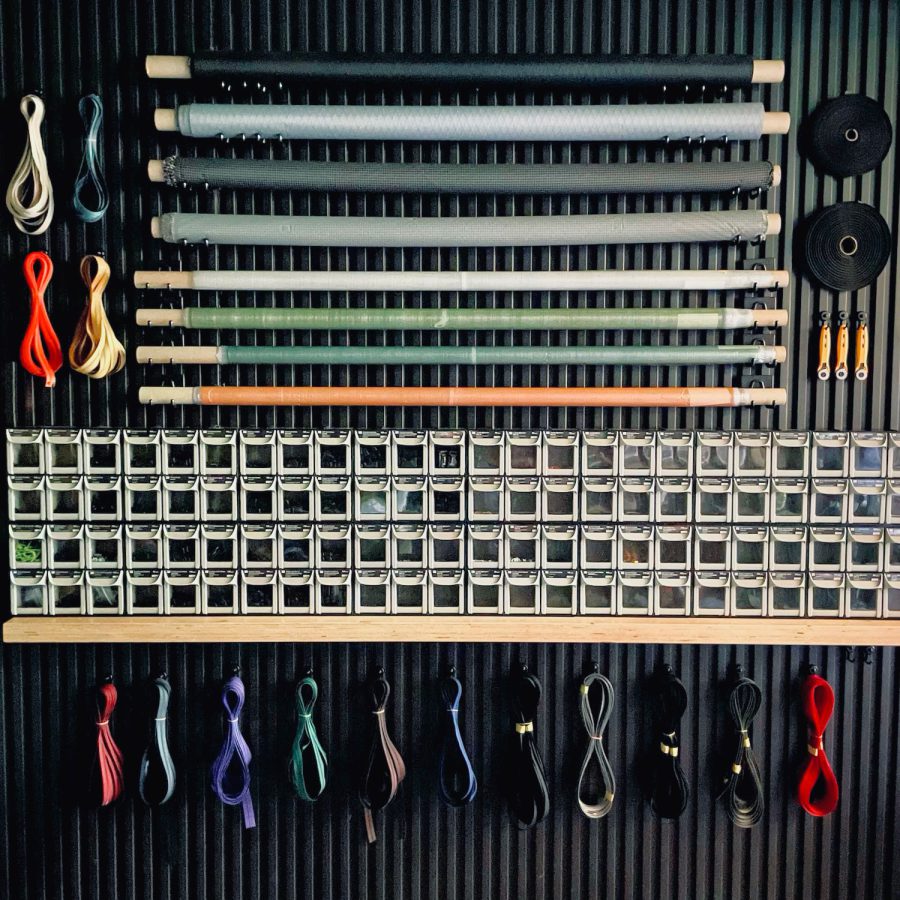

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…