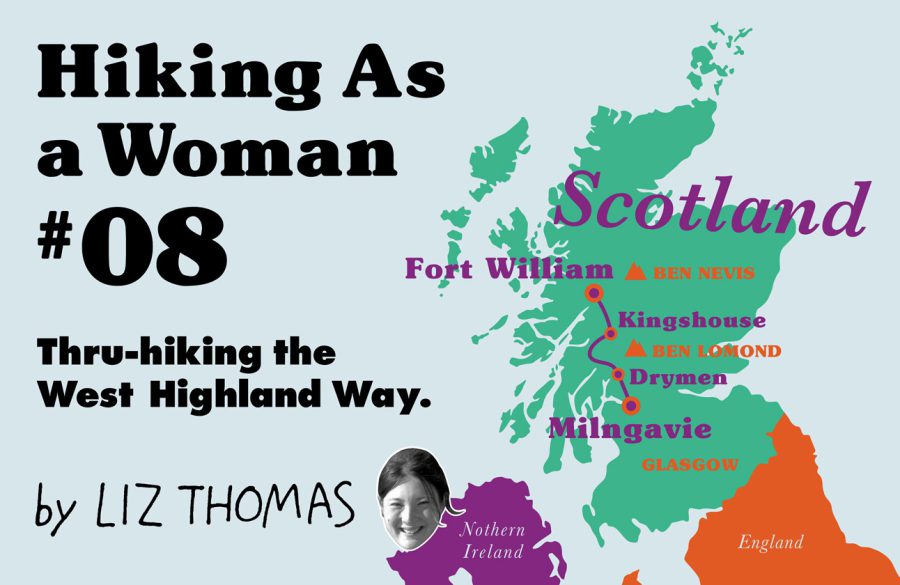

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#08 / スコットランドでのスルーハイキング

Hiking in Scotland: Thru-hiking the West Highland Way

For adventurers who love the outdoors, history, and travel, backpacking the West Highland Way in Scotland is a fantastic introduction to international walking. No matter your level of experience, the 154 km well-marked path gives you a taste for Highland life and epic views of the mountains, while providing numerous opportunities to venture off-trail into big mountains. Whether you are looking to camp every night and do the trail on the cheap or walk without a pack and stay in luxury B&B’s every night, I have never seen a trail better suited to being tailored to create your ideal outdoor experience.

The West Highland Way takes hikers from Milngavie (a rural “suburb” of Glasgow) to the foot of Ben Nevis, the highest peak in the United Kingdom. Logistics were surprisingly easy: I walked out the door of my hostel in Glasgow and walked 16 km right to the trailhead, although it is also easy to take a train to the starting point. The trail ends in the town of Fort William, a few blocks away from the train and bus station, where you can easily get a ride back to Glasgow and the airport. The trail is easy to plan and navigate, even if you don’t speak English. Yet, while I saw many Europeans hiking the trail, surprisingly, there were few Americans and no one from Asia on the trail!

The West Highland Way is routed past hostels, inns, and towns where you can easily get meals, food, a shower, and a bed. While the trail never goes more than 16 km without a resupply opportunity, at times, it still feels remote and wild. Scotland is a surprisingly sparsely populated country. Although my hiking partner and I walked the trail during peak season in July, at a time when foreigners were flocking to the United Kingdom due to a favorable exchange rate, we were shocked at how often we found ourselves without a single other person in view—even above treeline. For those looking for even bigger adventure and more solitude, you can take numerous side trails up into the big peaks of Scotland (called Munros), where navigation can be tricky and it is unlikely you will see anyone.

The trail starts in the Lowlands of Scotland on wide, relatively flat track. It was an excellent breaking in period for the trip. We rolled through sheep pastures, oak trees, past rock wall fences, and near small lochs (lakes), giving us ample time to adjust to the spirit of the trail.

Scotland has among the world’s most progressive camping laws, called the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, which allows you to wild camp—even on private property like ranches and farms—as long as you 1) are discreet, 2) do not leave any trash, and 3) do not make a fire. The Code is based on old Scottish traditions, but was officially made law in 2003. It requires a certain level of responsibility, and hikers must take care not to harm livestock and to close sheep gates as they travel.

Nonetheless, the first 21 km feel more populated than the rest of the trail, and don’t provide a lot of wild camping opportunities. Instead, there are numerous Bed & Breakfasts or paid campsites on farms where you can ease into the challenge of the hike.

One of my favorite parts of the West Highland Way is how it mingles the outdoors with travel experiences. After 10 km, the trail travels right past a true cultural highlight: a Scottish whisky distillery, Glengoyne Distillery, which has been called the most beautiful in Scotland. We took a break from hiking that morning for the hour-long tour (9 pounds, and includes a dram).

Admittedly, whisky distillery aside, the Lowlands portion of the hike—the walk from Glasgow and the first 21 km—were not my favorite. But as we ventured deeper into the Highlands, I came to appreciate the impressiveness of knowing I had walked from a busy urban area into the remote wildlands. I can’t think of too many other established trails that offer that opportunity, though I imagine the less popular choice of walking from the Highlands into Glasgow in the opposite direction may be disappointing in terms of scenery.

In the Lowlands, the trail travels through hedgerow ecosystems, a centuries-old man-made area that borders fields and farms with woodlands. We also saw many farms, ranches, and pastures. While well-suited for flower, bird, and butterfly watching, I was excited to reach our first forest on the first afternoon, the Garadhbam Forest. This was the first area with great wild camping spots. Scotland has historically been more forested than other portions of the British Isles, especially 2000 or more years ago before the Romans first reached Scotland, when wild bears still lived. Yet, by the 18th century, much of the woodland had been logged to meet the needs of the Industrial Revolution, farming, and the British shipping industry. Now, environmental groups are attempting to replant native trees, although conifer plantations abound along the West Highland Way.

An early highlight of the trip was crossing the first moorland—a treeless expanse of heather with the first views of the famous Loch Lomond. Just off the West Highland Way is the treeless Conic Hill (361 meters) with extraordinary views of the lake and area. By surface area, Loch Lomond is the largest inland lake in the British Isles and is well-known abroad due to the Scottish Folk Song “The Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond.” Loch Lomond and the Trossachs (the nearby mountain range) is Scotland’s first national park, designated surprisingly recently—in 2002. The national park status means that for about 13 km, wild camping is not allowed—pretty much the only area in the entire country besides Her Majesty the Queen’s property. Luckily, there are numerous public campgrounds, Bed & Breakfasts, hotels, and hostels throughout this area. While these areas filled up quickly and we did not have reservations, we found that the campsites were very accommodating to thru-hikers.

One of the best parts of the West Highland Way was the kindness of the locals along the way. Every person we met along the Way seemed to go out of their way to help us—which is becoming increasingly rare on popular trails elsewhere. While tipping is rare in Scotland, I was so grateful that I often left something extra for those who helped us.

The West Highland Way traverses near Ben Lomond, the southernmost Munro—a distinction given to peaks over 3,000 feet (914 m). Despite the rainy, foggy weather (I expected as much for Scotland), I climbed Ben Lomond via the Ptarmigan Traverse. It was one of the most fun dayhikes I have ever done. And when I was down from the peak, it was a pleasure to warm up, dry off, and eat a hot meal at the pub below the mountain before continuing on.

There are two free mountain huts along the Way. Called bothies, these four-sided shelters have a fireplace and offer hikers a respite from the rain. However, while I anticipated the notorious rain in Scotland to be torrential downpours all day, every day, in fact, the weather ended up being quite manageable. The weather was often misty and humid, but never hot. It would sprinkle and there would be light rain. Because the Way sticks mostly to valleys and traverses the sides of mountains instead of the peaks, very rarely is the rain heavy or the wind extreme. In fact, the worst weather we encountered in Scotland was when we took side trails to climb the mountains—not on the trail itself.

Another highlight of the Way is the opportunity to eat traditional Scottish food, a cuisine seemingly designed to warm up the wet and hungry traveler. Almost every day, I ate haggis and neeps and tatties—minced lamb or deer’s liver and offal served with mashed turnips and potatoes. While it sounds unappetizing, the dish was quite satisfying when cold and soaked. Many of the trailside pubs and restaurants also have a wide array of Scottish beers and whisky at surprisingly reasonable prices. Despite Scotland’s reputation for bad food, I found the cuisine delicious, if lacking in vegetables.

Although the West Highland Way was completed in the 1980, the trail is based on old “drovers roads”, paths used by cattlemen three hundred years ago to bring livestock to graze and market. It also utilizes wide military roads built in the 18th century to hunt down Jacobite rebels. The trail is mostly on single track or on wider tracks closed to motor vehicles. It’s usually not very steep and sticks to valleys and the contours of mountains, making it well suited for young and older people alike. Yet, the Way provides great access to the high peaks of Scotland including a few that are so far into the wilds that they are rare for peak baggers to climb.

Unlike some long distance treks, the Way is free of bears or large wild cats. However, we saw lots of red deer, roe deer, grouse and mountain hare. There are rarer animals, too: the pine marten, small wildcats, otter, and wild hedgehogs.

The heather moorlands, with low growing shrubs and acidic soil, are one of Scotland’s most iconic ecosystems. It is home to the bogs, a wetland which accumulates centuries’ worth of old moss, creating an ecosystem low in nutrients. This makes it a perfect home for carnivorous plants, which eat insects to make up for nutritional deficiencies in the soil. I was very excited to spot the flesh-eating sundew in the wild!

The truly spectacular part of the Way is traveling so close to the big Munros that the Highlands are famous for. These treeless peaks rise up steeply from the valleys below, making the traveler feel small. While I’ve hiked in areas with much higher peaks, the Munros’ green slopes surrounded by dark clouds and mist have an epic feel that echoes Lord of the Rings. It’s very easy to imagine that this was the land that inspired J.R.R. Tolkien.

While experienced hikers may find the Way itself to be easy—it stays mostly in valleys—there are plenty of opportunities to turn it into a challenging trip. Scotland’s peaks may not be as big as those found in other countries, but they are difficult, often gaining 700 m of elevation on steep, rocky terrain. The West Highland Way is perfectly situated for tagging some of these peaks or for doing high traverses above the Way. While some of the Munros—like the UK’s highest peak, Ben Nevis—have wide, easy to follow paths, many Munros require cross-country travel and navigation. Scotland’s weather is often rainy and misty, making finding your way particularly difficult when you can’t see 5 m ahead of you. Because the way to the peaks can often be boggy, swampy, steep, and require fording swollen creeks, there are ample opportunities for adventure.

For me, summiting Beinn Dorain (1,076 m) and Beinn an Dothaidh (1,004 m) was a particular challenge. I experienced the true Scotland mountain-climbing experience: 45 km per hour wind, sideways rain, slippery slopes, and little visibility. There was a lot to love about these peaks, though. I started in the afternoon from a nice restaurant in the town of Bridge of Orchy, where I left my hiking partner to spend a few hours reading and drinking warm beverages instead of tackling a few peaks. Four and half hours later, I was soaking wet, had been slightly terrified about not finding my way back, and then relieved to find myself warm, dry, and with hot food back at the restaurant. I got to experience the full range of emotions associated with hiking. This is what I love about hiking. I can think of few other activities where the adventurer gets to better capture all those feelings in so little time.

The last 51 km of the West Highland Way are complete joy. It feels like you are walking through a fantasy land of green hills, waterfalls, and rainbows. At times, it was so beautiful you would think it was a set designed for a movie. In all of my hiking, I have never seen so many rainbows, which arc over the valleys and hover over the little villages you visit. It’s a joy to hike for a few hours, warm up and dry off in a historic restaurant, and then venture into high hills and the rain again, only to return to another warm pub.

As a fan of travel as a way to learn about a country and as a history buff, I enjoyed visiting the historic towns along the Way. Much of the economy in these towns relies on tourism, but they are reinventing themselves in fun and creative ways. Glencoe is a famous mountain-lovers’ town near the Way, with its iconic peak, Buachaille Etive Mor guarding the entrance to the valley. But the mining town of Kinlochleven nearby is trying to turn itself into an outdoor mecca, as well, with the creation of the world’s largest indoor ice climbing gym and the UK’s biggest featured climbing gym. I visited and found a café, restaurant, brewery, and gear shop inside a building previously used as a smelter. Similarly, the town of Fort William turned an old church into a climbing gym. For the walker willing to venture beyond the beaten path, there are amusing things to find all along the Way.

The highlight of the Way was the unofficial ending atop Ben Nevis, the UK’s highest peak. We took a little-used semi-cross country route up the Carn Mor Dearg Arête—called the best non-technical route in the UK. More importantly, the CMD was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen. Despite the hordes of tourists atop Ben Nevis, this route to the top allowed me to feel like my hiking partner and I were the only people in the great mountain’s shadow. It was exhilarating to be atop a narrow spine of rocks looking into two uninhabited basins—knowing full well that in fact there were plenty of people not so far away.

Whether this is your first long hike, you are hiking with kids, or are an experienced hiker, there is something for everyone on the West Highland Way. On a trail designed for the Walker, the Way is a gateway to adventure—whatever your traveling style may be.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

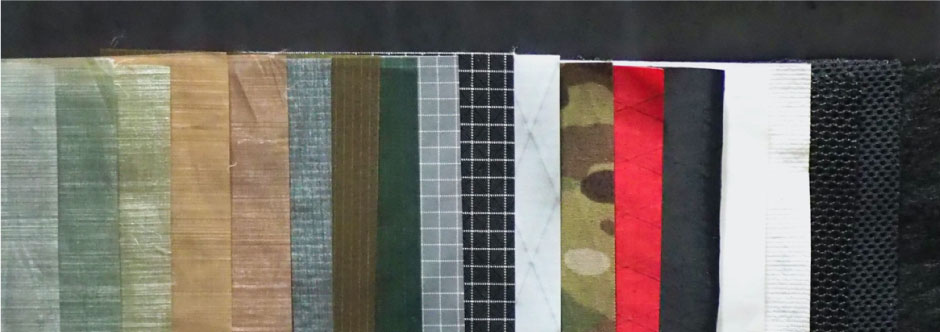

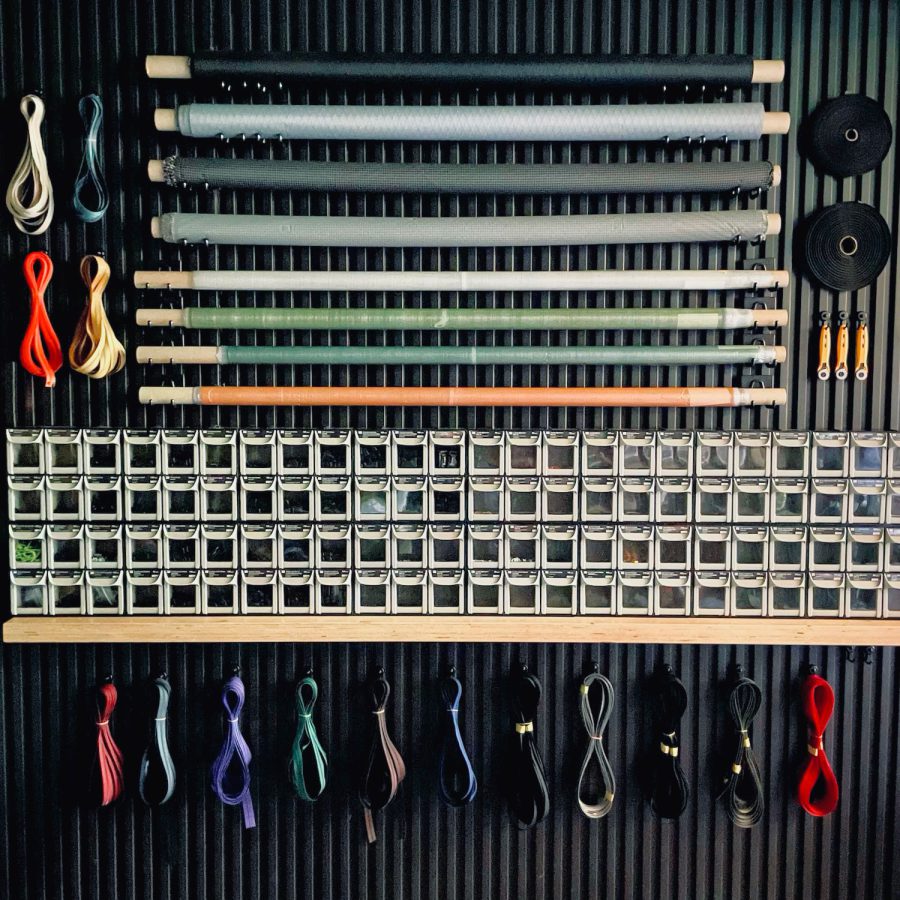

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…