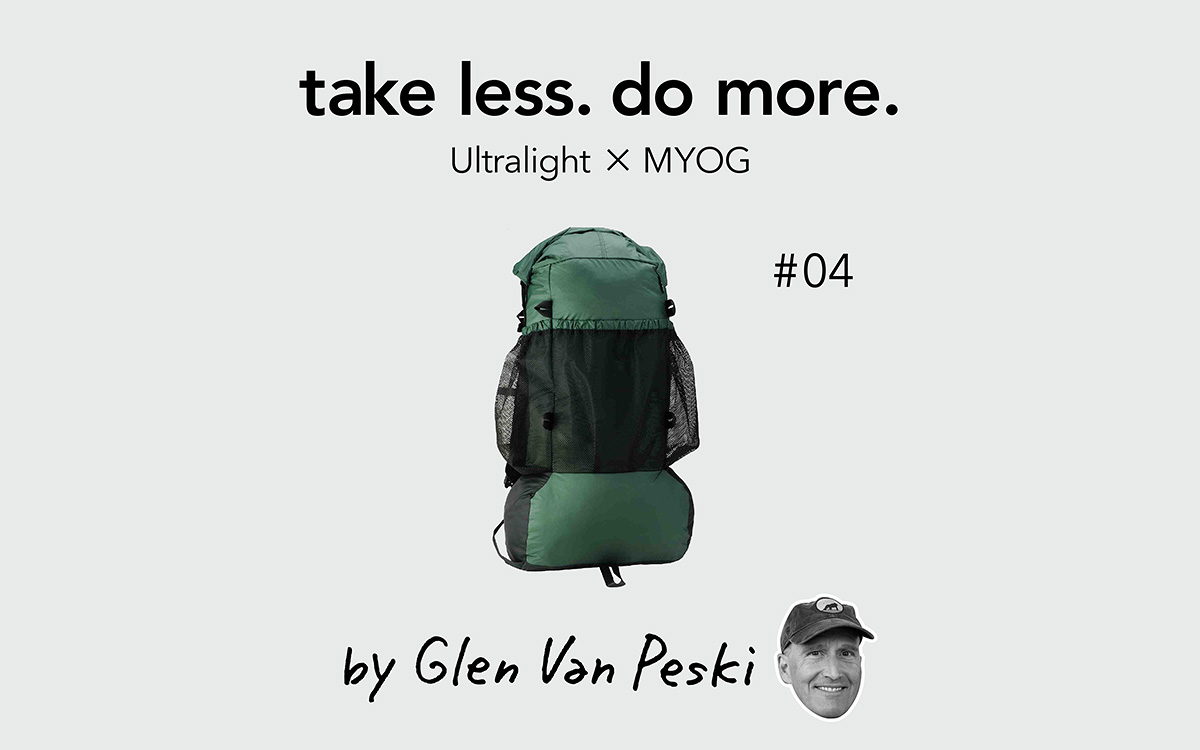

take less. do more. 〜 ウルトラライトとMAKE YOUR OWN GEAR by グレン・ヴァン・ペスキ | #04 ULバックパックのエポック「G4」のデザイン思想

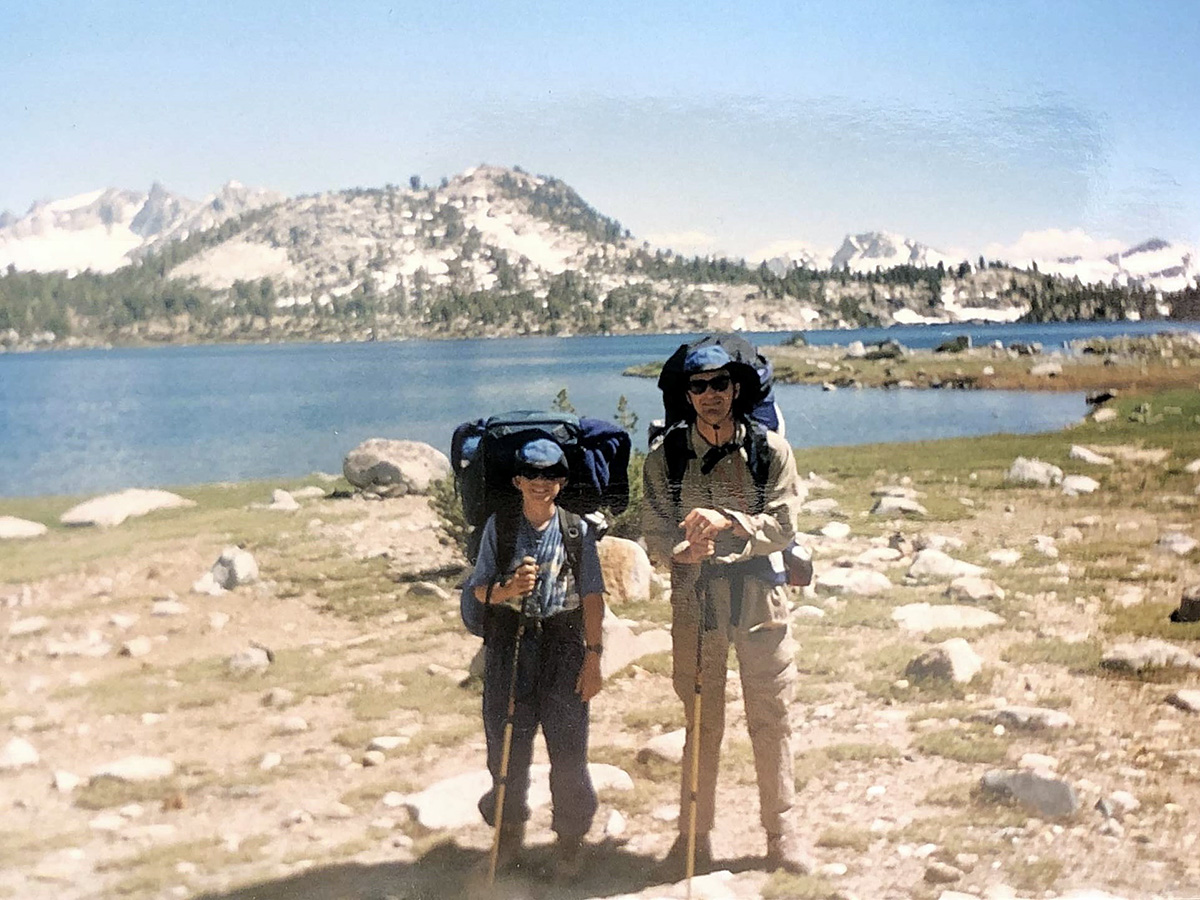

The design of the G4 pack was a process that started with my very first pack sewn, the G1. When our son Brian joined Boy Scouts, the troop was very active and the capstone backpacking trip was a week-long trek in the Sierra of California. I had left my old Kelty frame pack and other camping gear from my own Boy Scout days on the east coast when I rode my bicycle 6,700 kilometers from Massachusetts to California in 1976 after graduating high school. So Brian and I went down to our local REI to gear up.

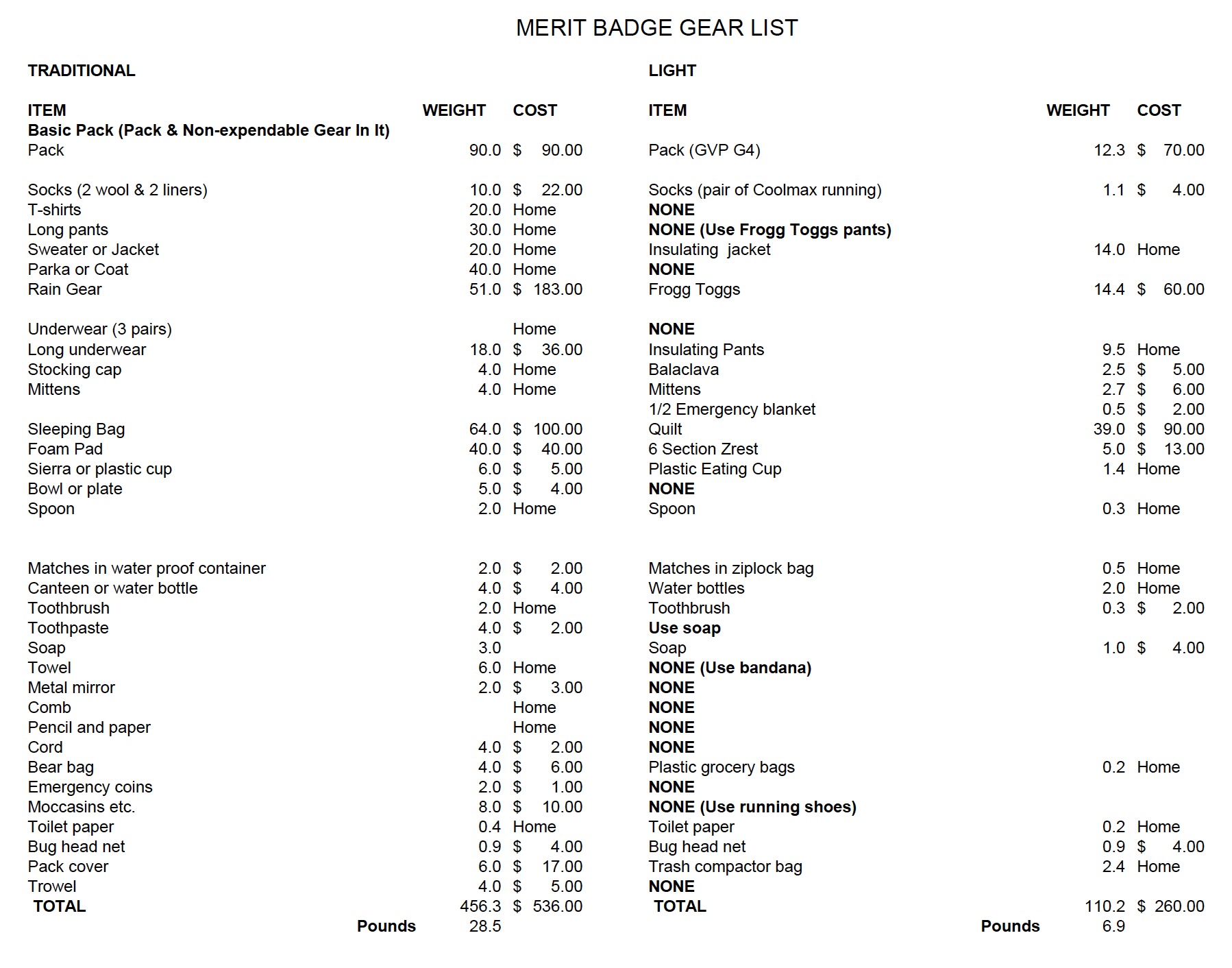

At that time, the new internal frame packs were the latest design. When we told them we were headed for a week in the Sierra, they sold us new backpacks, down sleeping bags, inflatable sleeping pads, a stove, fuel canister, pots, plates and cups, and more. We did some training hikes with the troop, which enabled us to get familiar with our new gear. When we set out on that first Sierra trek, my loaded pack weighed 32 kg. I was carrying our 2-person tent and cooking equipment, but Brian’s pack was still heavy for a young boy. Carrying the heavy loads made for long days of hiking to get our mileage in, and lots of bruised and tired boys (and adults).

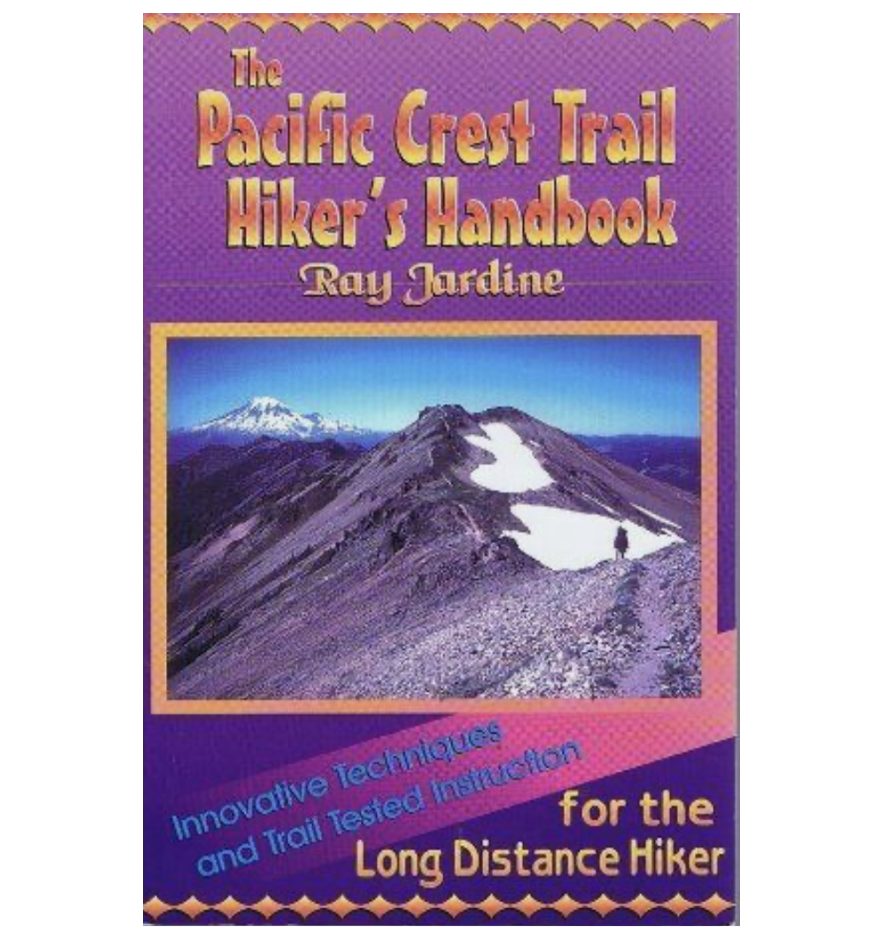

About this time, the Scoutmaster and my friend Read Miller read Ray Jardine’s book, The Pacific Crest Trail Hiker’s Handbook, first printed in 1992. Read decided to section-hike the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), and eagerly read the book detailing how Jardine had traveled with a base pack weight (all gear not worn, not including food and water) of around 4 kg. I got my own copy of the book, and we spent hours poring over it’s advice.

That internal pack they had sold me at REI before our trip weighed 3.4 kg empty! As I listed all my gear on a spreadsheet, the pack was the heaviest item by far. I knew I would have to lighten everything as a system, but the pack seemed like a good piece of gear to start with. My mother firmly believed that every kid should leave home knowing how to cook, bake and sew. So I already knew how to sew, and in fact had made some kits by Frostline and Holubar while in high school.

So I ordered some fabric and buckles, and the Alpine Rucksack pattern mentioned by Jardine in his book. It didn’t look big enough to me, so I ended up starting from scratch, and sewed a pack. It was HUGE, with loads of webbing and buckles. It was still a lot lighter than my REI internal frame pack, but it lacked many of the features. As I took it on some training hikes, I thought about how to improve it, and then sewed a second and third pack.

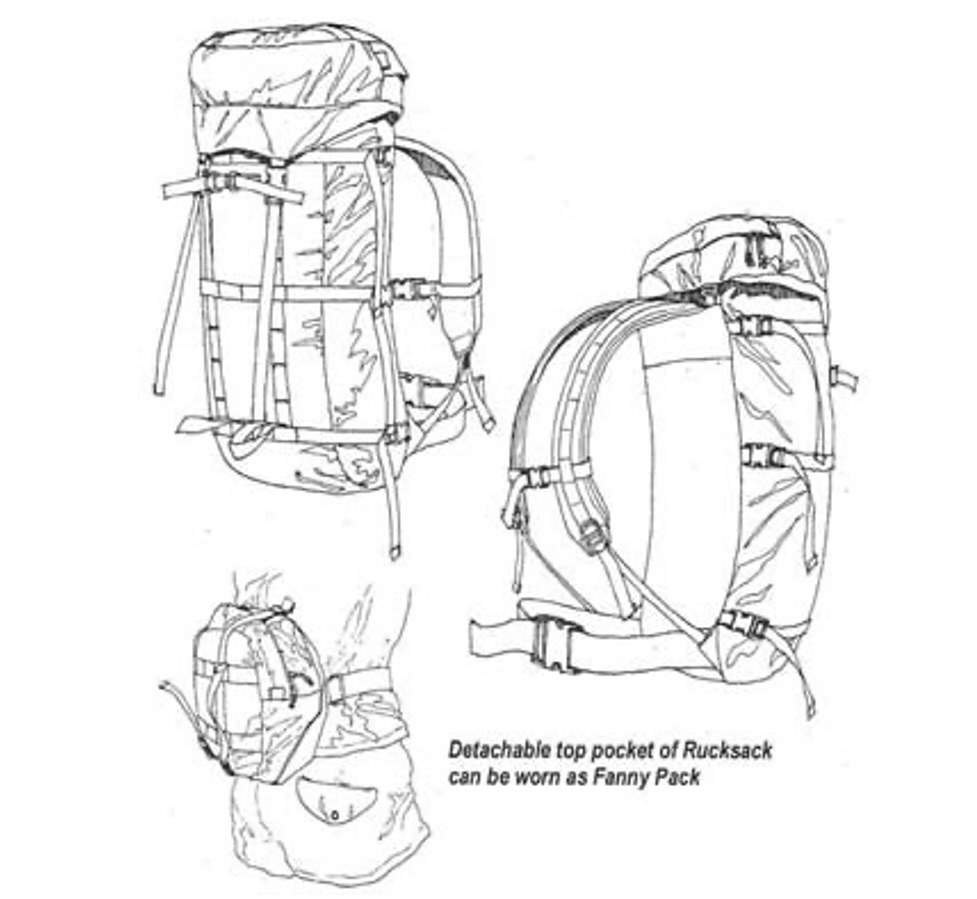

One of the key principles of lightening pack weight is dual use. If you can take one piece of gear that performs two, or even three functions, you can then leave the unneeded gear at home. I applied this principle in the design of my fourth pack, the G4. My sleeping pad, a Z-Rest, became the frame of the pack when it was folded up and inserted into the sleeves on the back of the pack. My fleece sleeping socks, which kept my feet warm at night, were stuffed into the shoulder straps to become padding during the day. My gloves and warm beanie, not needed during the day, became padding for the waist belt.

Another key principle of lightening pack weight is to use the lightest materials available that are adequate for the intended use. The early G4 packs were made out of 2.2 oz. ripstop nylon, with more durable 4 oz. oxford cloth in areas of high stress or abrasion. Instead of webbing I used nylon ribbon where it would suffice. The closure was a simple roll top with hook and loop closure tabs on the sides.

There were some additional, more subtle design features of the G4. The bottom of the bag was expanded, and was designed to carry the sleeping bag without it being forced into a stuff sack. When carrying a lighter sleeping bag, it’s important to maximize its performance. One way to do this is to avoid over-compressing it. With gear protected by an internal trash bag when rain is expected, the sleeping bag can be allowed to expand and take up more space, to maintain optimal performance.

For hiking efficiency, it’s nice to not have to open your pack very often. The G4 was designed with huge mesh side pockets. This allowed for the storage of a tent, perhaps still wet from the overnight dew or rain, without getting other gear damp. And, it was easy to pull out the tent and spread it over some bushes during lunch, to allow it to dry out in the sunny breezes. For the desert sections of the PCT, the huge side pockets allowed the transport of 2 – 2 l. bottles in each pocket, 4 l. total in addition to whatever other containers you had. The rear sleeping pad holder configuration allowed for a water reservoir to be carried between the pad and the pack. This meant that when coming to a water source, it was quick and easy to pull out and fill the reservoir, without ever needing to open the pack. And the water, one of the heavier and dense pieces of your load, was carried next to your back, where the short moment arm minimized the effective weight. The large mesh pocket on the pack allowed for carrying items for easy access, like hygiene items, first aid, snacks. The mesh allowed enough visibility that it was quick and easy to find the item you wanted.

Making your own designs means that you can make different choices. For instance, I used a half inch (13 mm) seam allowance, larger than typical. This allowed true double stitching for strength, helped protect against the fabric unraveling, and maintained the integrity of the seams. When we started binding seams, we did it with nylon Grosgrain ribbon instead of webbing. On some later packs I experimented with using French seams to eliminate the binding and save the weight of the Grosgrain ribbon.

Through the application of these principles, the G4 pack, which originally sold for $70, weighed about 350 g. While it looks crude by today’s standards, it was groundbreaking in its time. I put the plans on the internet for free so people could make their own G4. You can still purchase the printed pattern (with improved instructions) or a kit from Quest Outfitters, where the G4 is one of their most-requested patterns. The materials I used are primitive compared to today’s options, but were a lot lighter than the heavy cordura fabrics that were standard for packs at that time. Occasionally when I’m speaking, someone will come up afterwards with a well-used and much-beloved G4 pack from those early days.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

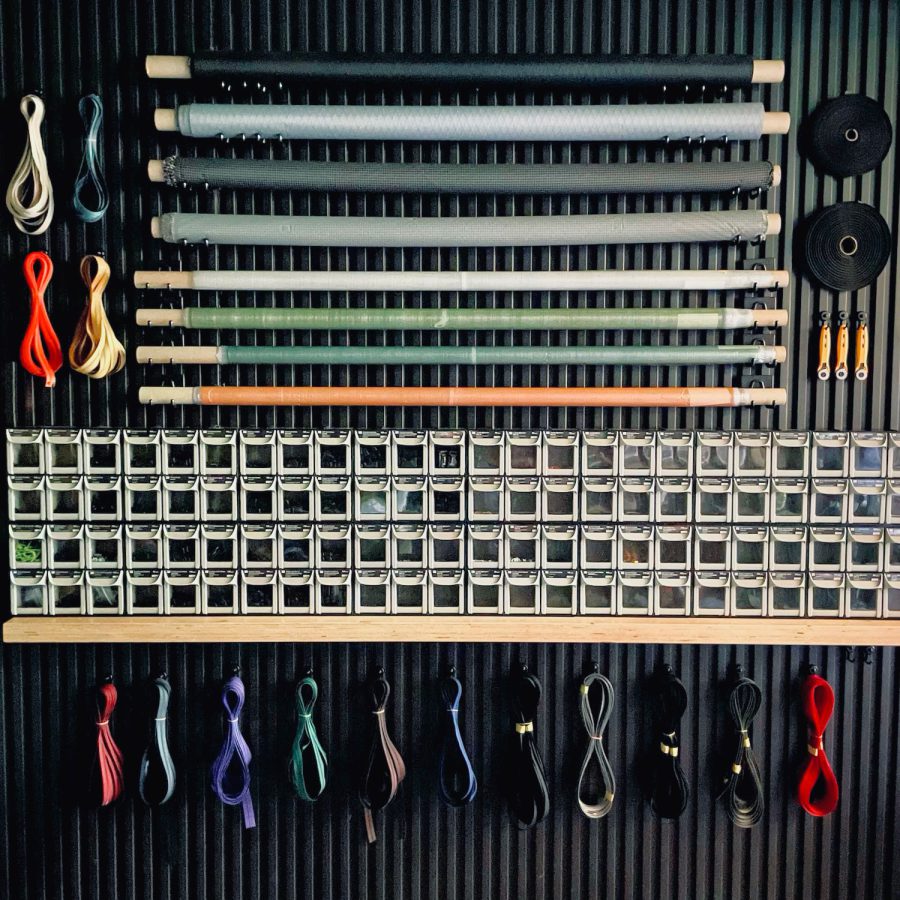

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…