リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#15 / 日本人ハイカーはどう思われてる?<前編>アメリカ人ハイカーとPCTAの視点

What do Americans think of Japanese People Hiking in the U.S.? Part 1

Text: Liz Thomas, Photo: Liz Thomas, Funada Yasuaki

It takes courage to go on a long distance hike. And it takes even more bravery to walk a long trail in a different country. Yet every year, many Japanese people go to the U.S. to hike the John

Muir Trail or Pacific Crest Trail. But as more hikers come to America to walk trails, what do Americans think of international walkers? These days, I sometimes read news about Americans who do not like foreigners. I hope more than anything, that this is not true within the hiking community. But I needed to know: Do American hikers like that there are foreigners on the PCT? Or do they wish they had the trail to themselves? Is America a welcoming place for hikers from Japan? To answer this question, I interviewed Americans who interact with Japanese hikers on and off the trail from the trail organizations who provide information, to trail angels, to American hikers themselves.

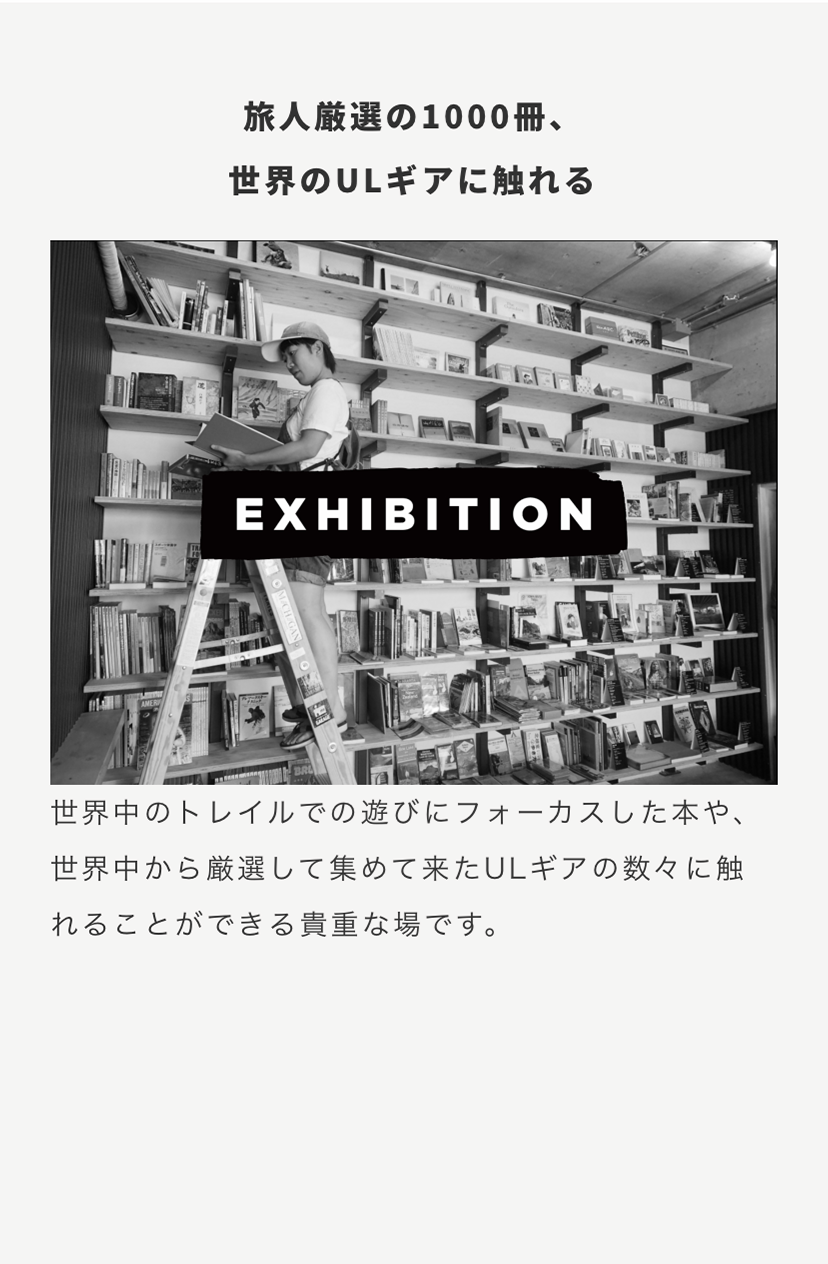

Mt McLaughlin and the red lava trail beneath it is one of the most iconic spots on the PCT

* * *

I started my quest to understand what Americans think of Japanese hikers at the beginning: with the Pacific Crest Trail Association. Their website is the first place many hikers look when they dream of walking the PCT. The PCTA is the non-profit that partners with the Forest Service to administer the PCT. It’s also the website where hikers apply for a permit to hike the PCT.

Jack Haskel, the Trail Information Specialist at the Pacific Crest Trail Association told me, “Almost one third of 2017’s PCT thru-hikers are international.” That’s one reason why the PCTA has gone to special effort to make the trail more welcoming to international hikers.

For example, in the 2018 hiking season, the PCTA changed the first day to apply for a permit to hike the PCT. The date to apply for a permit previously was in February but has recently been moved to November. This is helpful for international hikers because it gives plenty of time to make visa arrangements and to book expensive international flights. As Jack described to me, it would be such a shame for a hiker to obtain a visa and buy a plane ticket only to be denied a hiking permit.

The PCT in Washington at a signed intersection.

But the PCTA also recognizes there are special concerns that international hikers need to learn before coming to the U.S.—everything from how to obtain a visa to tipping culture at American restaurants. There’s a lot of information that the PCTA suggests international hikers learn before coming to the U.S.

Whether you are hiking all of the PCT, part of it, or the JMT, the PCTA makes it clear that it is important to learn the differences between hiking in America and hiking in other parts of the world, including Japan. Hiking in America involves being in wilderness and far from towns or huts or tea houses for many days at a time. In many parts of the American West, campfires are illegal. On the PCT and JMT, hikers rarely stay in established campgrounds with dozens of other people. There are rarely pit toilets or showers available. In America, it is seen as preferable to camp by yourself.

American hiking style stresses independence and personal responsibility. One reason is because America is so big and the wilderness areas so far from cities. Compared to hiking in many countries, it’s much more difficult to be rescued if something goes wrong.

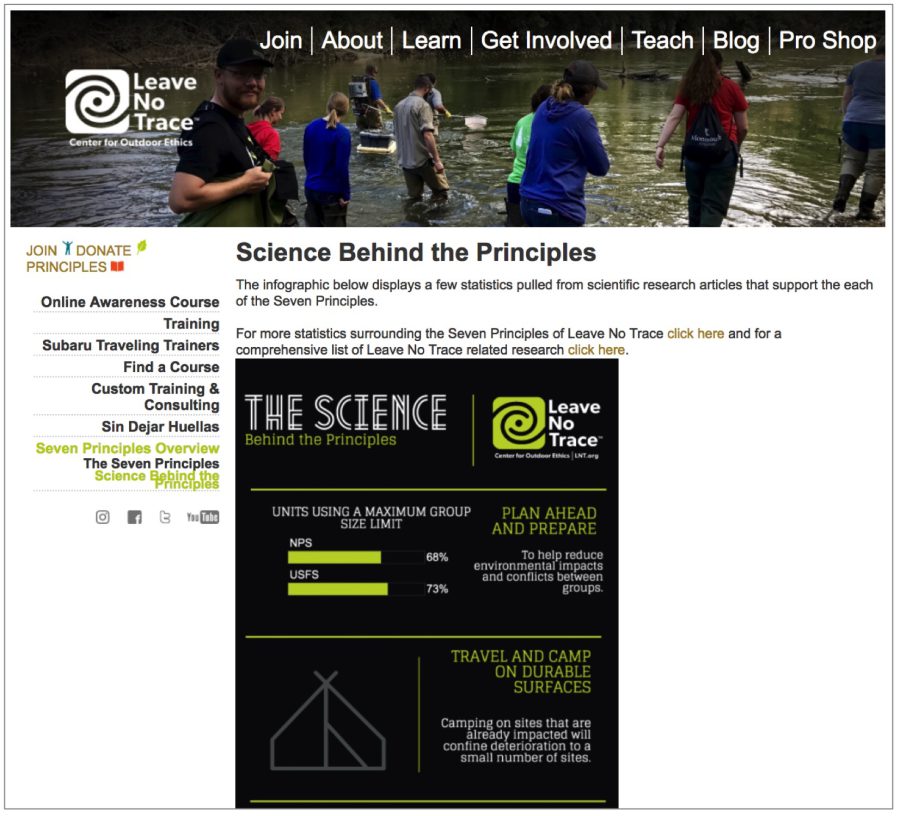

Rooted in that idea that individuals are responsible for nature and themselves is the Leave No Trace wilderness ethics. In America, Leave No Trace wilderness ethics are the rules of the mountains. While Japanese hikers tend to be respectful of Leave No Trace, the rules are a uniquely American concept and are new to many international hikers. Leave No Trace’s most notable rules involve packing out all trash, properly disposing of human waste, reducing campfire impacts, and being mindful of how a campsite’s selection can change the natural area. The PCTA believes that all international hikers, as well as domestic hikers, must learn and practice Leave No Trace wilderness ethics.

The PCTA encourages hikers to take care while crossing rivers and creeks in the Sierra.

As with all hikers, the PCTA suggests that Japanese hikers “buddy-up” with other hikers when traveling through the more dangerous parts of the trail like the snow-covered Sierra mountain section or before attempting any scary fords of rivers and creeks. All hikers should practice and be confident in snow travel and fording skills before attempting the PCT. Additionally, hikers should familiarize themselves with best practices when traveling through waterless desert, which is an new hiking ecosystem for many international hikers.

The PCTA encourages hikers to walk in groups and take care while hiking in the snow covered Sierra.

My impression is that the PCTA is welcoming and encouraging of Japanese and other international visitors coming to hike. But the PCTA wants to make sure that, like all hikers, that Japanese hikers have the information, skills, and experience to succeed on their trip.

* * *

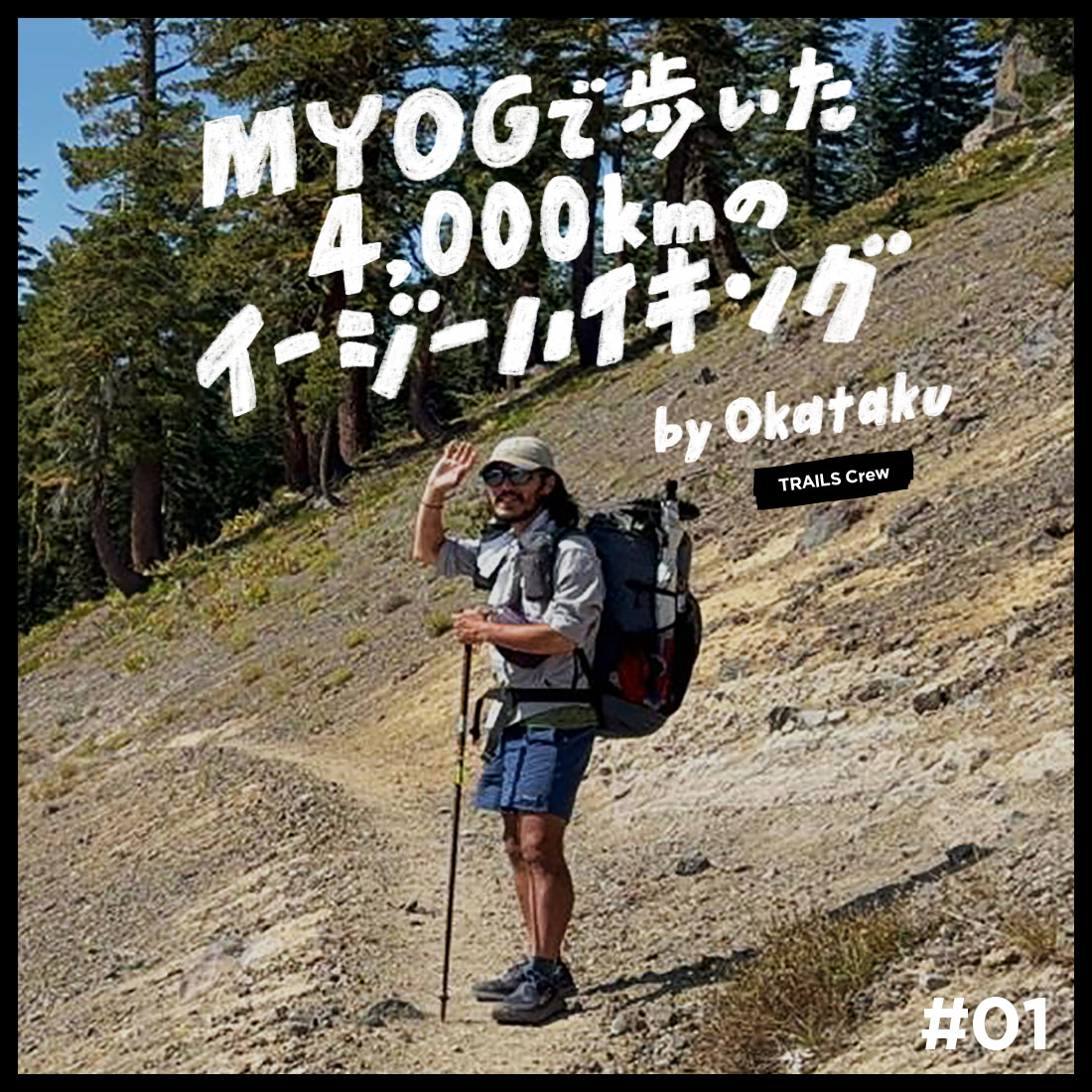

In 2011, Yasuaki Funada (trail name: “Yas,” “Rock Steady,” and “V8”) became the first Japanese hiker to have walk all three Triple Crown Trails—the entire length of the Pacific Crest Trail, Continental Divide Trail, and Appalachian Trail. In 2014, TRAILS interviewed Yas about his experience. But since then, perhaps inspired by Funada, it has become even more common for Japanese hikers to walk American long trails.

Although I hiked with Yas on the PCT, because I speak some Japanese, I had a different interaction with him than an American who doesn’t speak any Japanese. To understand what an American hiker who doesn’t speak Japanese thought of Yas, I interviewed Mike Unger, who hiked with and around Funada along much of the Continental Divide Trail. The CDT is a ~3,100-mile trek from Canada to Mexico along the Rocky Mountains. Although Mike had hiked parts of the PCT with Europeans, Yas was the first Japanese hiker that Mike had hiked with. Mike provided insight as to what that experience was like.

A background to Funada and Mike’s hike: the Continental Divide Trail in 2010, did not have as much signed trail as it does today. Much of the journey then was cross-country or on unmarked trails. The high country is often covered with snow in early and late season. The CDT is still more remote than many other long trails. Mike Unger and Yas traveled together in and around a group of around a dozen hikers, which was mostly Americans but also included a man from Australia and a man from New Zealand. Although it was not planned this way, eight of those hikers, including Yas and Mike, started at the Canadian border on their first day together. Over the 3,100 mile journey, sometimes the group would split into smaller groups, or one person would go faster or others would stay behind. This is the nature of groups on a long trail.

Immediately, the first thing Mike says of Yas is, “he has the best navigation skills of anyone I’ve met. I was behind him the whole time in the Bob Marshall wilderness and there was a lot of snow. He would hike with a map and compass in one hand. We followed his foot prints. Occasionally, there would be breaks in the snow. And his footprints would lead [from the snow] right to the trail.”

The CDT can often be covered in snow early and late in the hiking season.

I wonder if learning to read map and compass in Japan made Yas such a strong navigator. In Japan, the mountains are steep and forested, so a hiker must be very good with map and compass because there is no line of sight to navigate. In the American West, so often we have the luxury of navigating above treeline, where a line of sight to our destination makes it easy to figure out where we need to go. “Yas could see terrain and make sense of it and just go,” Mike says.

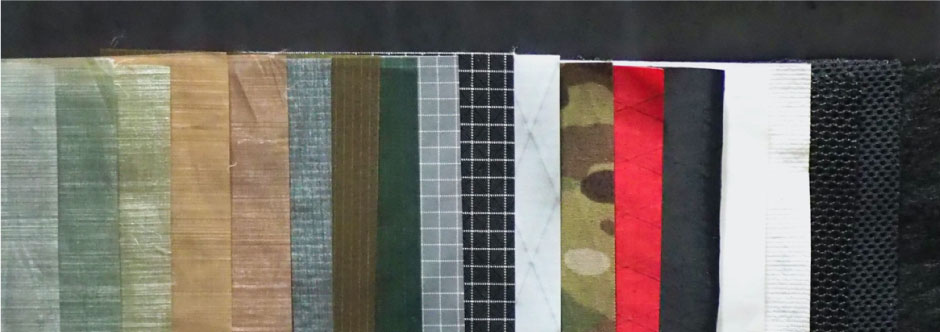

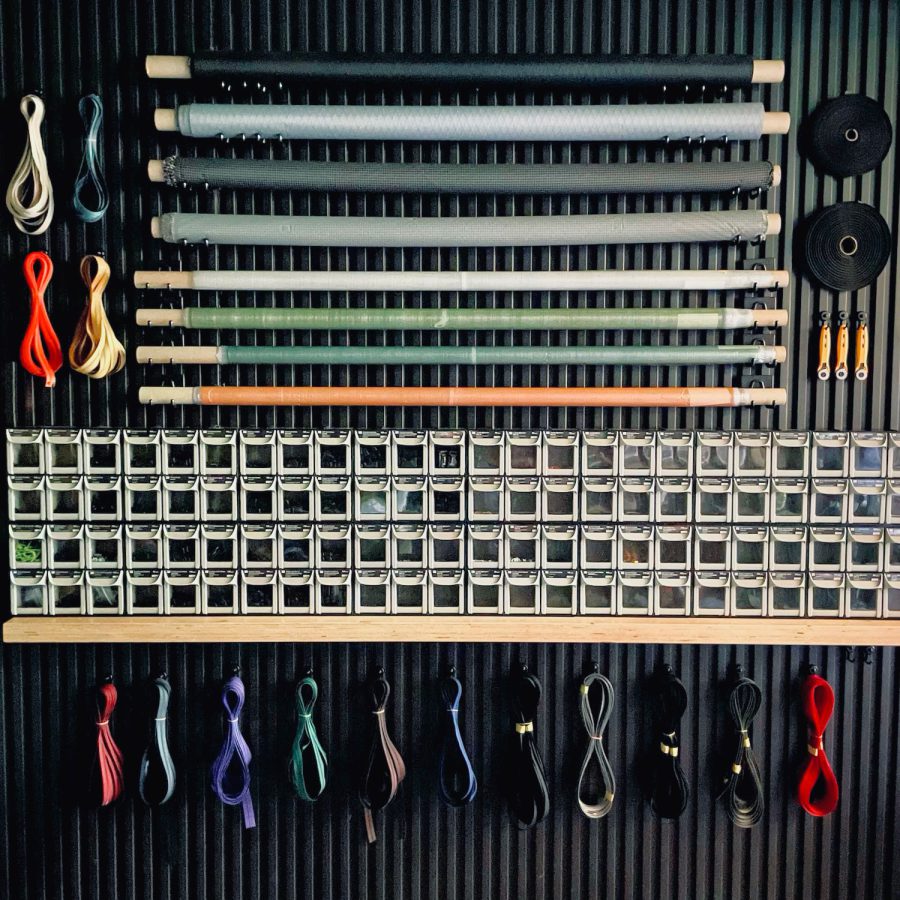

Mike was also impressed by Yas’s gear: “In 2010, there weren’t a lot of people who were really into making their own gear. He was the first hiker who took it super seriously. He had a sub-10 pound kit. He made his own pack, his own quilt, his own tarp. I remember he made his own fleece mittens.”

As I talk with Mike, I wonder what inspired Yas to make his own gear. Where did he learn the skills? When I studied in elementary school in Japan, it was a big shock for me to have home economics be part of the school curriculum. Boys and girls both learned how to sew. That is very uncommon in America. I wonder aloud that perhaps Yas learned to sew in school.

The CDT is an especially remote trail.

The Continental Divide Trail goes through some remote parts of America that tourists from other countries rarely visit. The locals don’t often see a lot of people who don’t look like them. I wondered how the townspeople treated Yas. Even most American hikers who live in the city find some of these small towns to be culturally very different than at home.

Wyoming on the CDT is the heart of cowboy country.

Mike doesn’t remember Yas having any issues. Mike says, “he hiked basically alone through the state of Wyoming.” Wyoming is one the most remote, cowboy parts of the CDT. “I didn’t see him from Lander until Pie Town,” a distance of more than 1,000 miles. “He wanted to hike alone for most of it, but he also wanted to finish [the trail] with us.”

Related Articles

ZINE – IN THE TRAIL TODAY #02 | 長旅をあきらめていた人のための、2週間で行く『SECTION HIKING』world trail編

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#14 / アメリカ人は日本のどこをハイクしたい? <前編>トレイル認知度ランキング

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…