リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#28 / 北米ハイキング・カルチャーの最前線のハイカーたちは、どこへ向かっている? (前編)

What do edgy hikers hike?

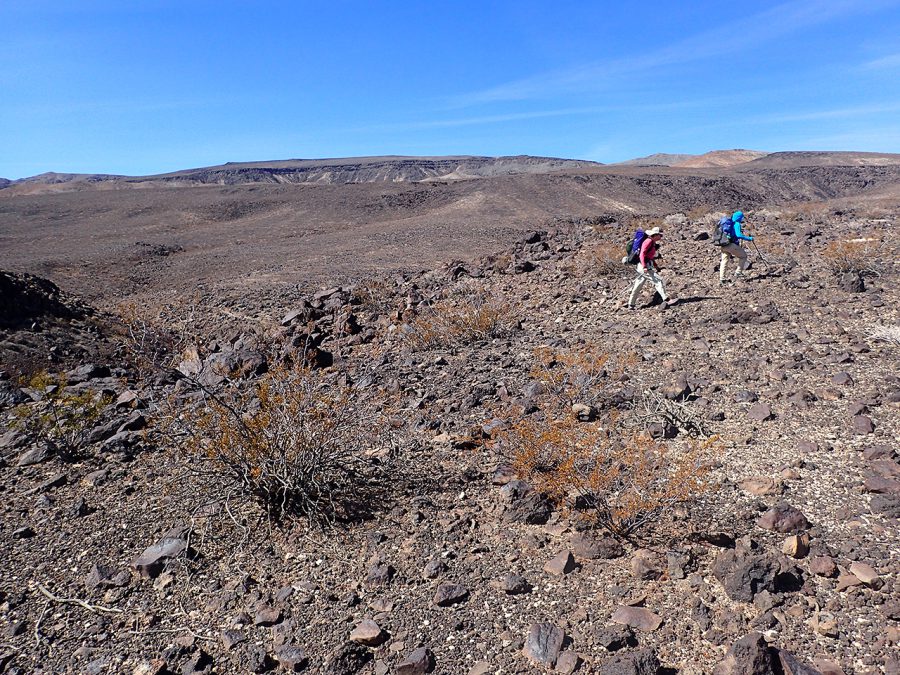

The most experienced and skilled long distance hikers are often found these days not on well-established trails, but on routes.

Like traditional thru-hiking trails, Thru-hiking Routes are long distance hiking adventures. While it’s difficult to come up with one thing that makes a route different than established trails, many routes lack one or more of these things:

1. A trail organization or volunteers who maintain the route.

2. Signage or labels with the trail’s name on most mapsets.

3. Physical trail. The route may include sections of off-trail travel, including cross-country or bushwhacking.

A route usually includes a mix of existing shorter trails, dirt roads, and off-trail cross-country travel. Because routes usually don’t have signs (or at least signs that explicitly say the name of the route), hikers have to navigate and be more mentally aware than on most big name thru-hikes.

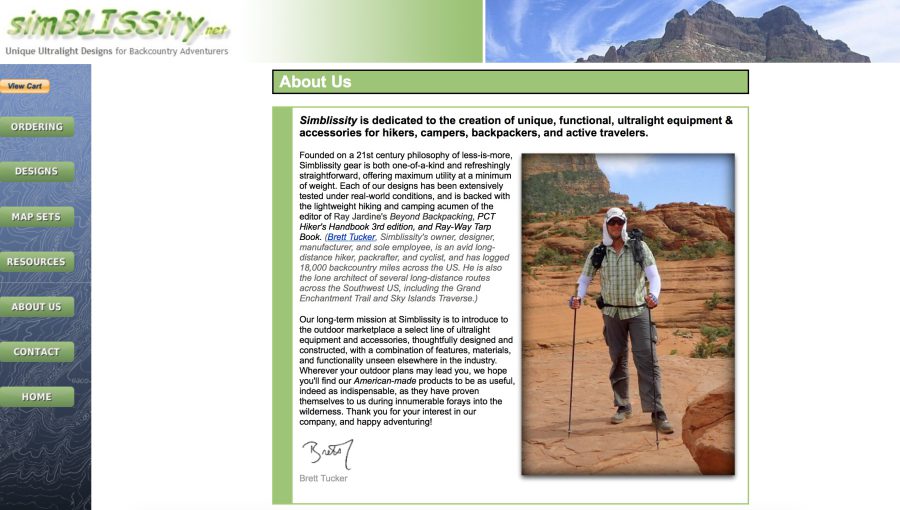

While there are many hikers developing their own routes, the most famed route-maker in the U.S. hiking community is Brett Tucker, who goes by the trailname Simblissity. He runs a route and map company called Simblissity, named after his trailname.

Simblissity routes include:

■ The Low to High route: 130 miles from Badwater to Mt. Whitney (the lowest point in the lower 48 states to the highest point)

■ The Grand Enchantment Trail: a 1200-mile long desert route from Phoenix, Arizona to Albuquerque, New Mexico

■ The Sky Island Traverse: visits 10 high points in Arizona that are “islands” of alpine vegetation surrounded by lower elevations of desert

■ The Mogollon Rim Trail: 480 miles

■ The Northern New Mexico Loop: a 500-mile loop from Santa Fe, NM north to the high mountains and back.

When Brett Tucker announces that he’s made a new route, it’s big news in the hiking community. Celebrity hikers jump at the opportunity to be the first to hike the new route. Online fan communities develop around each of his routes. Hikers in these communities share information about water availability and trail towns as well as trail conditions and navigationally tricky areas, much as PCT or CDT Facebook groups become gathering areas to swap information.

I was fortunate enough to interview Brett Tucker’s partner in building the Simblissity mapping projects, Melissa “Treehugger” Spencer. Treehugger calls herself “Vice President of Public Relations” at Simblissity (a company with only two people).

Although she is quite modest about her own hiking accomplishments, Treehugger has an impressive hiking resume including numerous long trails (including the PCT with her dog, Sage) as well as difficult routes throughout the Southwest and beyond.

Melissa shared with me the goals and the details involved with developing what many hikers consider to be the highest quality long distance hiking routes in the U.S.

This interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

Liz:My first question for you is what do you think the difference is between a route and a trail?

Melissa:I was on a long dayhike thinking about this question. The more I thought about it, the more I thought there isn’t a difference.

The Pacific Northwest Trail [which has National Scenic Status and signage and a trail association] has more bushwhacking in it than several of our routes combined.

There’s no signage on the Bigfoot Trail whatsoever. There’s also bushwhacking. But it is going to be a [designated] National Recreation Trail.

The Oregon Desert Trail has a trail association [but is considered route and is almost all cross-country travel].

The CDT in New Mexico has a lot of parts that aren’t trail at all, either. [But they have a trail association and signage].

So if the difference between trails and routes isn’t bushwhacking or signage or having a trail association, I don’t know what it is.

We’ve named some of our routes at Simblissity as “Trail,” which can get confusing. [For example, the ‘Grand Enchantment Trail’ is the name of one of the Simblissity routes].

I can tell you that we’re never going to have any signage [on our routes]. We want our routes to just be there and have no one even know that it’s there. We want people to have to look at a map and think about it instead of just blindly walking from place to place.

Liz:What do you think a route offers that a trail doesn’t?

Melissa:A route can be more challenging. It can give you more adventure. But mostly I think a route is customized to what you want the experience to be. For example, the Bigfoot Trail strives to see the highest concentration of pine trees in the country. The Bend Ale Trail hits all the breweries [in Bend, Oregon]. The Hayduke Trail visits all the national parks in the southwest. With a route, it can be customized [to where you want to go and what you want to see.]

Also, the routes we create offer more solitude. But solitude is definitely not necessarily for everyone. [Your desire for solitude] can even depend on your stage of life.

[When I hiked the PCT], it was the right amount of socialness that I needed at that time. [It also] offered the perfect amount of solitude [for me at the time].

If you’re going to try a Brett Tucker route, I don’t think that you should hike it because you want to meet people!

Liz:I agree. A few years ago, I wanted a lot of solitude while I was thru-hiking routes. Now that I’ve been at home due to coronavirus for so long and can’t see my friends in person, I dream of hiking a social trail.

In your experience, what kind of hikers are choosing to walk routes instead of established trails like the Pacific Crest Trail or Continental Divide Trail? Is it hikers who have hiked the PCT and CDT and are looking for something wilder with more navigational challenges? Or is it people who have never hiked a long distance route before?

Melissa:It’s actually a surprising mix. We probably get a majority of people who are at a higher level [of thru-hiking skills]. I think a lot of thru hikers who have already hiked other long distance trails are looking for a different new kind of adventure.

But then we also get a lot of people from the area that the routes go through. They hear about it and they’re super interested because it’s in their backyard. On the Mogollon Rim Trail, we met these locals that were putting together their own route. They were really interested in what we already had on the ground.

There’s a fair amount of people that hike these routes who tell us they live in Phoenix and are interested in hiking a route that goes to Albuquerque, or visa versa. They’re interested to see our maps and hike the Grand Enchantment Route because it’s in their backyard.

Liz:There’s more people out there creating routes than most hikers realize. You and Brett create routes professionally and are considered the creme-de-la-creme–the highest tier–of people who are designing routes.

What would you say draws hikers to hike the Simblissity routes over other routes? Is it that you have a website and a mapset? Is it the quality of the mapsets? Or is the quality or destinations?

Melissa:One of our major goals when we’re putting together a route is to make it repeatable so that people have all the tools they need to hike it. Most people who are putting together hiking routes are doing it for their own weekend or summer adventures. We go to great lengths to make sure that what we put together is a repeatable experience [for other thru-hikers with experience].

Liz:What are your goals in designing a route?

Melissa:We don’t want to send people on some super roundabout trip to a point of interest that only interests us. We try to keep it logical and to hit landmarks that would interest most people.

We try to keep our routes on trails as much as possible because we think that most people don’t [want to walk on] pavement. Our own goals definitely get weaved in there and we make assumptions of what we think people want–for example, solitude.

Obviously we also weigh how beautiful the route is. But we’ll generally gravitate towards something that doesn’t have a bunch of people. At least some of the people hiking Simblissity routes have already hiked a long distance trail, and maybe are looking for more solitude [than the Big Trails have to offer]. I think that’s why at least some people gravitate to a Simblissity route.

Liz:When I was working for the Continental Divide Trail Coalition and doing other trail research in school about how National Scenic Trails are routed, it seemed like there were a lot of politics involved in deciding where a trail goes. For example, the PCT goes through Mt. Rainier National Park, and it’s a pretty spot, but it’s not the most scenic spot in the Park. The most beautiful parts of the Park already have a lot of foot traffic. The PCT was seen as a way to bring foot traffic to a part of the Park that might otherwise not attract a lot of people.

With a route, do you feel like you have the freedom to have people go places that a trail organization might not?

Melissa:Everyone who puts together a route has certain goals. Trail organizations have their goals, too. With the Pacific Crest Trail, the [PCTA and Forest Service] want to make sure that the [trail’s] grade isn’t too steep for horses [so most portions of the PCT are no steeper than a 10% grade]. With some other trail, like the Arizona Trail, they want to make sure that [the grade and trail tread] is legitimate for bikes.

With Simblissity routes, we focus on foot traffic, so there can be a little bit of adventure like crossing a river or cross-country travel.

Related Articles

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#27 / 海外ロングトレイルの定番アプリ「Guthook」開発者インタビュー (前編)

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#26 / How Thru-hiking has changed <前編> スマホ時代のスルーハイカー

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

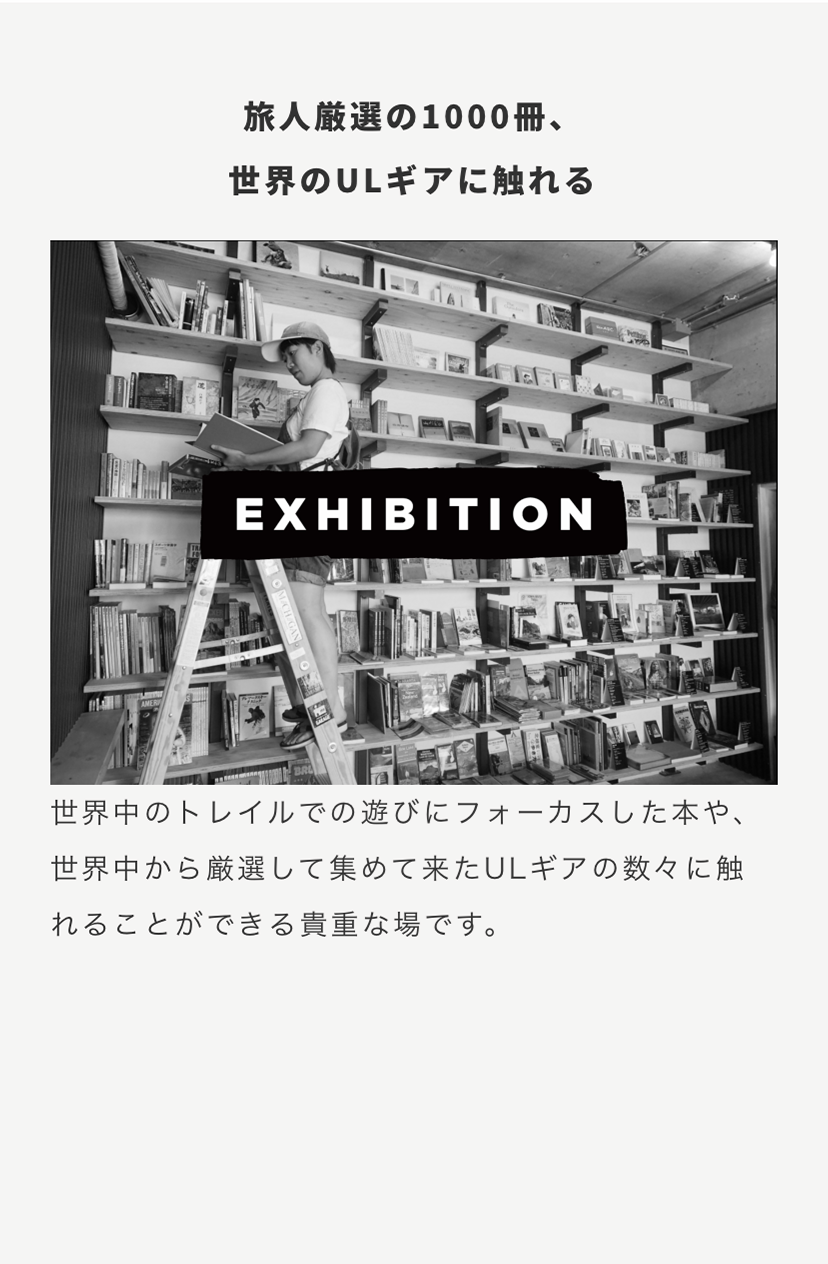

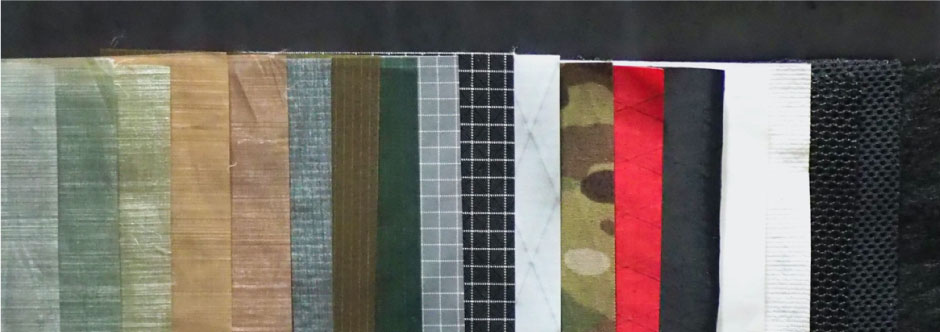

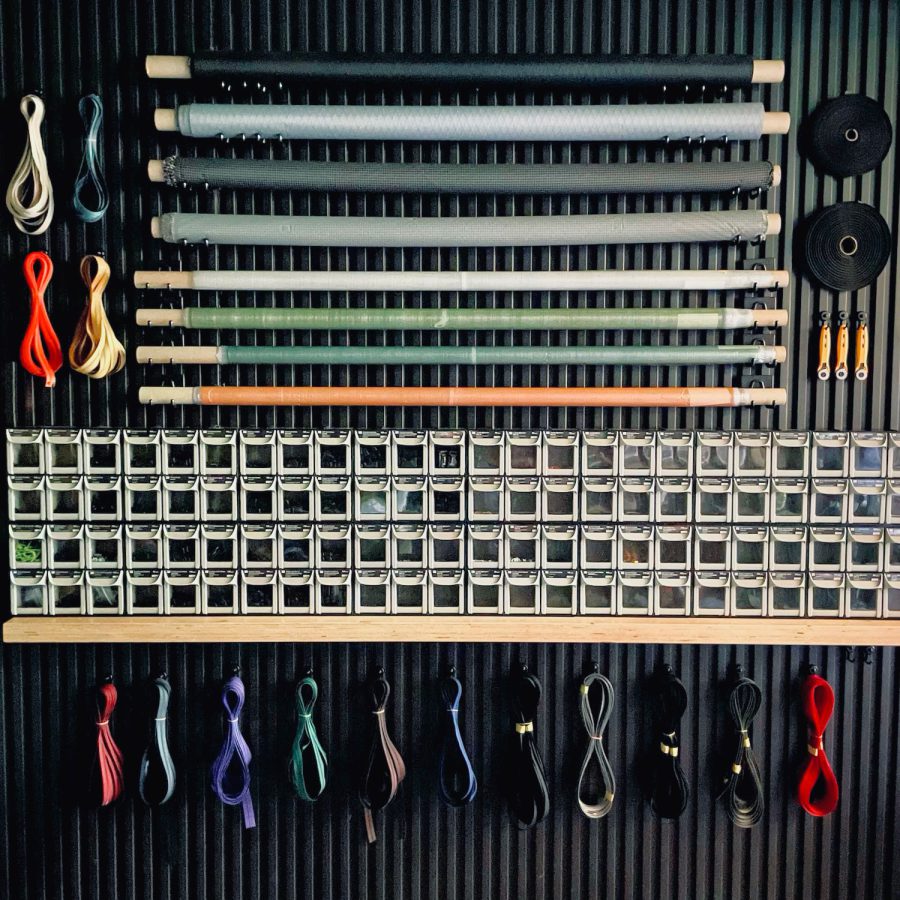

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…