リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#29 / 「with コロナ」のハイキング (後編) 〜人との接触を最小限にする方法〜

Hiking during coronavirus in American.(Part2)

In the last article, I explained guidelines for how to recreate responsibly during coronavirus. In this article, I describe two routes that edgy hikers are doing during 2020: the Sierra High Route and the Greater Yellowstone Loop. I’ll explain two different strategies to tackling routes during coronavirus—both intended to minimize contact with other humans.

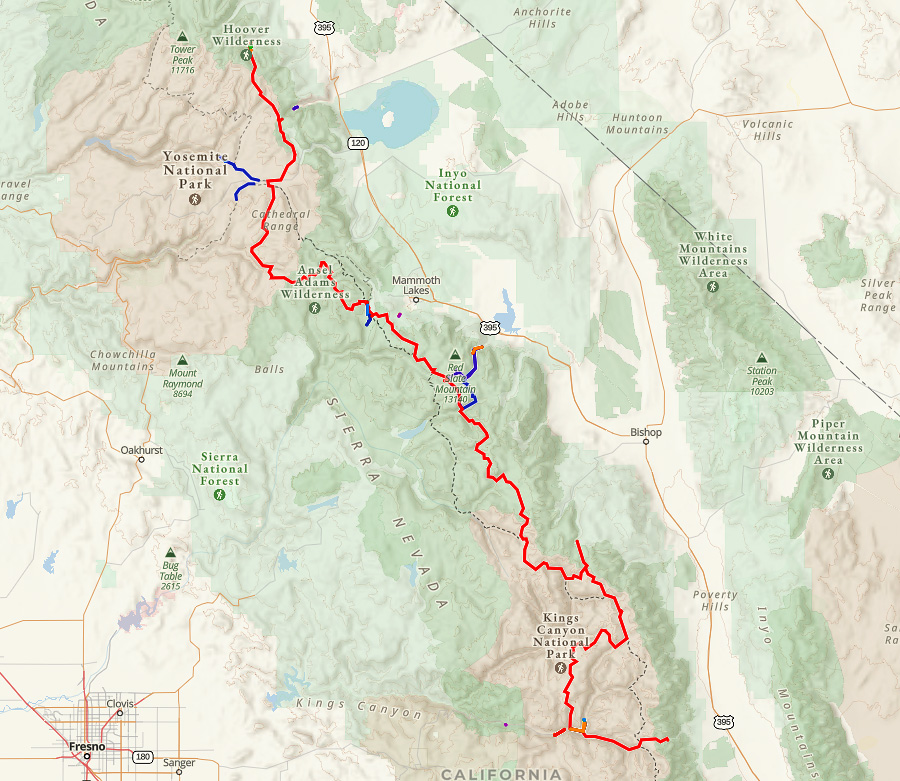

Off-Trail Loops

In an effort to stay within my region while hiking during COVID-19, I’ve been hiking loops based on the off-trail Sierra High Route. The route was developed in the early 1990s by rock climber Steve Roper and described in a guidebook of the same name. Although there isn’t an app, Justin “Trauma” Lichter drew the route on a digital map set that I printed and carried. I also exported the route as a GPX file, which I imported into my Gaia phone app to use as back-up navigation.

I’ve been on 4 mostly off-trail loops based on the Sierra High Route in the past two months. Each trip was 3 to 5 days. On almost every trip, I went at least 24 hours without seeing another human. I camped in lake basins where I was the only human there.

I got the idea to hike the Sierra High Route as a series of loops from another thru-hiker, Flamingo. Flamingo lives in the Bay Area within a few hours of the Sierra. Recreate Responsibly guidelines say that during coronavirus, shorter loop hikes within your state that don’t require resupply are better than thru-hiking. Flamingo thought section-hiking the Sierra High Route as a series of loops is a conscientious way to experience a long route during coronavirus.

However, on my most recent SHR trip, I learned that even with planning to avoid human contact, sometimes it is inevitable. My loop started at the popular Mosquito Pass trailhead to the 12,000-foot Mono Pass. Then I left the trail, heading cross country into the hanging valley in the Mono Recesses, joining the Sierra High Route. After 2 days on the SHR, I intersected and joined the Italy Pass Trail.

While the map showed I could connect to another trail over Morgan Pass back to my car, I discovered that trail had been destroyed in a recent rockslide. I would have to swing on an insecure rope over a chasm to get past the slide. I wasn’t going to risk my life. But I didn’t have enough food to retrace my steps on the SHR back to my car, either. I decided the safest option was to hike out to a nearby trailhead and hitchhike back to my car.

I thought I had planned and prepared my route to avoid any human contact. But being a thru-hiker is about being flexible and realizing some things will go wrong. I was carrying 4 different mapsets and pages from several guidebooks. I had emailed with hikers who had done the route recently. But all my focus had been on the difficult off-trail sections. I failed to read the trail descriptions and assumed the trails were passable because in my mind, trails were the “easy” part of this hike.

Because I hitchhiked and rode in a car with a stranger, I’ve been quarantining for the past two weeks and haven’t been able to hike. When I got home, I read about an off-trail pass that would have avoided the destroyed trail and still got me back to my car.

I’ve learned that when hiking during coronavirus, we need to be especially vigilant about research before we go. When my quarantine is over, I plan to return to my section-hike loops of the Sierra High Route. But next time, I’ll do better research.

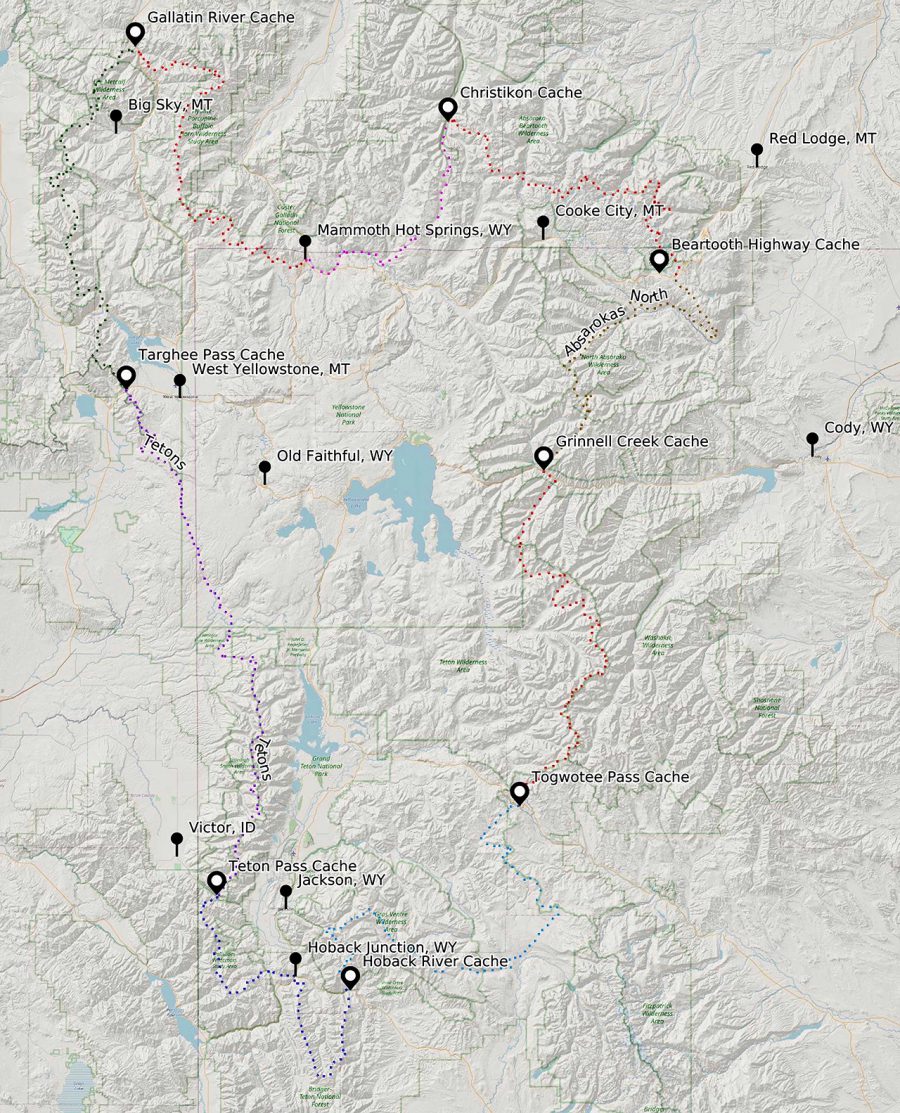

Cache Method or Support Vehicle Method

Some hikers exploring new routes have chosen to cache or bury their food instead of going into trail towns to resupply. Other hikers ask family or friends to follow them in a van on a semi-supported hike. The idea is that to reduce exposing small towns to hiker’s “big city germs,” it’s better for hikers to have fewer contacts with trail towns. However, trail town economies rely on tourism, so many small towns are at least (somewhat) happy for visitors.

“Larry Boy” didn’t want to be the jerk on the PCT—hiking on a trail even when trail organizations asked hikers to get off. He developed an 800-mile route in the Greater Yellowstone Region, which is within a few hours of where he lives. He planned the route on his computer mapping system during the spring based on a route developed by a thru-hiker named PepperFlake.

Larry Boy purposely hiked a loop to avoid need for transportation. He designed his route so he wouldn’t have to hitchhike or stay in hotels or hostels. Knowing he would want to minimize contact with people in trail towns, he mapped out places to cache food and extra gear like socks and batteries along the route, describing the planning process as “more like an expedition than a backpacking trip.” Before he started, he dropped off caches at trailheads. His goal was to be as respectful as possible and have months in the woods without contact with other humans.

After two months of hiking alone in the woods, Larry Boy’s plan to hike and avoid human contact during coronavirus was going well. Then, an unexpected injury interrupted his hike. In a one-in-a-million chance, while turning a corner, he startled a grizzly bear. It attacked him, swiping at his head and chest with its claws. After Larry Boy played dead for ten minutes, the bear left. But Larry Boy was bleeding profusely from his chest. As much as he wanted to have no contact with people during coronavirus, he realized he’d have to get off his route and go into a town for medical care.

Although Larry Boy had designed his route to minimize contact with people, in the end, he had to hitchhike to get to a hospital. Several local people in Wyoming volunteered to host and care for him as he recuperated from blood loss and receiving 37 stitches.

Despite his high level of planning, Larry Boy couldn’t plan for an accident this severe. Getting attacked by a bear has such a small risk of actually happening. Larry Boy did all the best practices for hiking in bear country. He had practiced what to do during a bear attack dozens of times. He made noise while hiking. He carried and knew how to use bear spray. But even best practices weren’t enough.

Things can always go wrong on a thru-hike. Luckily, Larry Boy is healing from the attack, did not contract coronavirus, and will be hiking another route in a few weeks once he has healed. Sometimes, even with all our precautions, we must accept there will always be risks.

Conclusion

Coronavirus has changed the distance hiking community. This week, the Pacific Crest Trail Association announced they will not be issuing 2021 thru-hiker permits. It may be a few years until we can thru-hike again like we used to. If we all have learned something from coronavirus, it is how lucky we were in the past to have thru-hiking. Every thru-hiker misses their friends and the ability to become friends with strangers. We miss trail angels and feeling safe being invited into strangers’ homes. We miss eating in restaurants and seeing new places and exploring far from home. Routes may be the closest thru-hikers will get to having a long trail experience for another season.

No matter what level of planning we do to avoid contact with others, just living in 2020 comes with a risk of having to rely on other people.

No matter how well we plan, things can and will go wrong. We will make mistakes. I’ve learned that routes—even when planned to minimize contact with other people—still have the same unpredictable challenges of hiking a long trail.

Even if Larry Boy and I didn’t hike this summer and instead opted to never leave our homes, things can go wrong. We could’ve fallen off a ladder in our backyard or sliced our hand while cutting open a bagel. Both situations would’ve required medical attention. It’s the same for driving a car. There’s a risk we’ll get in an accident. But we wear a seatbelt to mitigate the risk.

For hiking routes in 2020, the ways we can mitigate risk are to plan and prepare. We can minimize contact with others by hiking loops and following the Recreate Responsibly guidelines. Hiking during 2020 is like an expedition—every mistake has bigger consequences than usual. Ultimately, even more than before coronavirus, we do what we can to make sure that nothing goes wrong.

Related Articles

リズ・トーマスのハイキング・アズ・ア・ウーマン#29 / 「with コロナ」のハイキング (前編) 〜守るべき6つのガイドライン〜

「withコロナ」のロングトレイル(後編) | 海外のロングトレイル

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

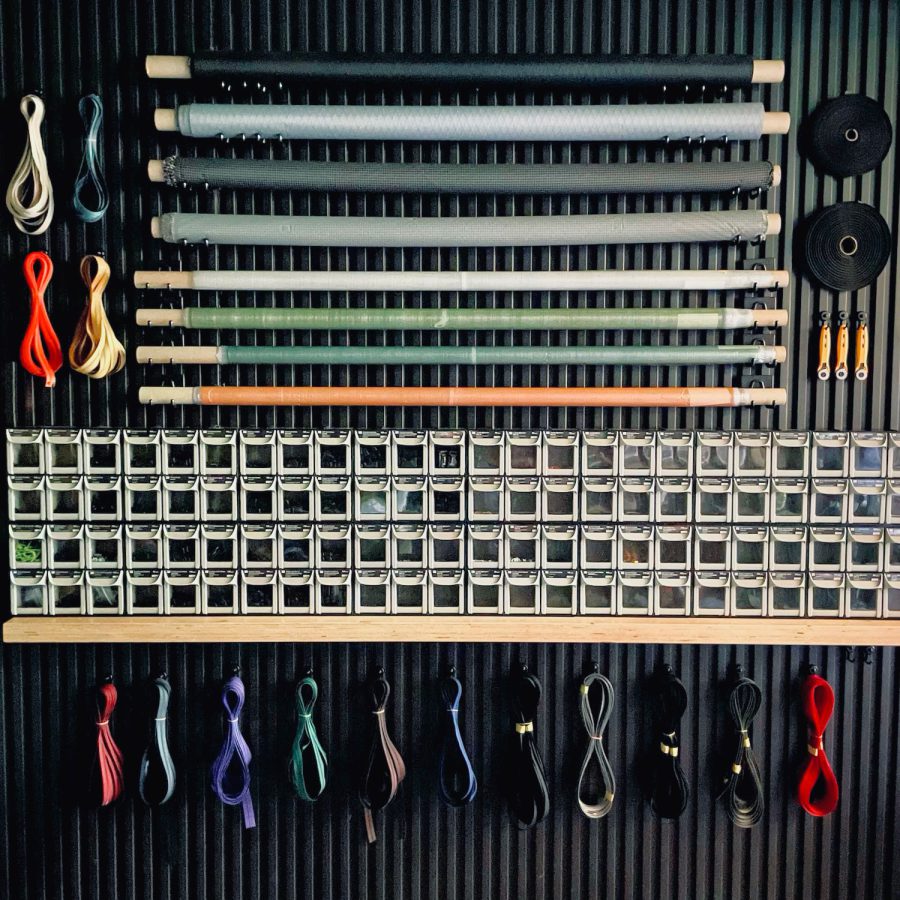

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…