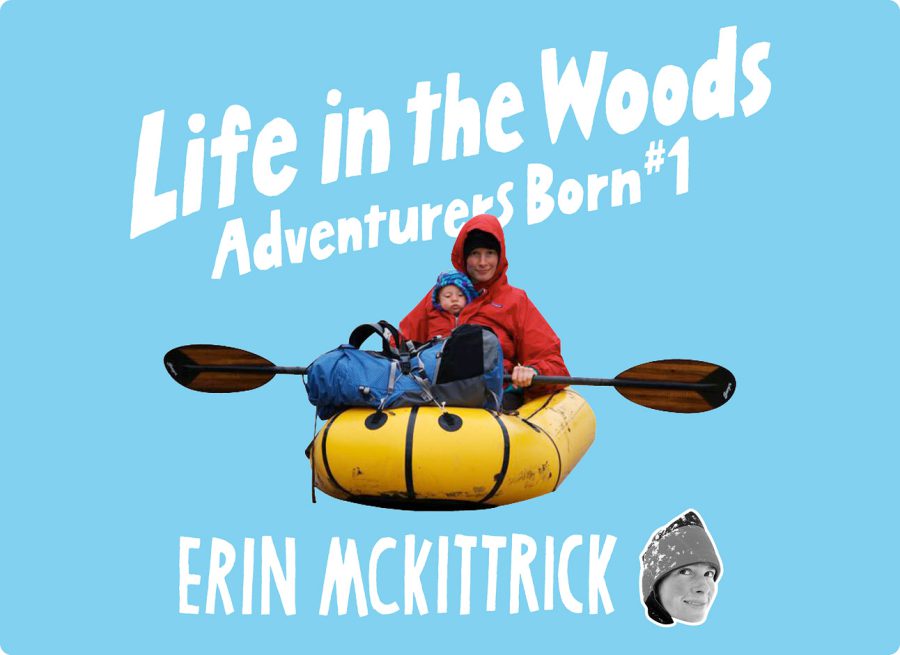

エリン・マキトリックのライフ・イン・ザ・ウッズ#1 /生まれながらの冒険家

■Adventurers Born

Adventure is often seen as the province of the young – something to do when you’re fit, broke, inexperienced, and lacking other commitments. Fifteen years ago, Hig (then my boyfriend) and I fit the bill perfectly. So in the summer after I graduated from college, we took off on an 830 mile trek through the wilderness of the Alaska Peninsula.

Our expensive mountaineering rainpants leaked in the first rain. Our inexpensive rafts had holes after the first river crossing. Our sleeping bag was too heavy. Our tarp was too small. Our food calculations were laughably low.

And somehow, although every one of those things mattered, none of them mattered enough. Poring over the map in the evenings, we counted each one of those 830 miles, measuring success in numbers that impressed us. Walking across the tundra in the blowing rain, I imagined myself an intrepid explorer. I felt proud. I felt alive. And I knew that something in my life had irreversibly changed.

Hig and I married. We left the city, and spent a year walking 4,000 miles to the Aleutian Islands. Our expeditions became the framework of our lives.

The first things we learned on these journeys were eminently practical. Estimating food for a months-long trek is not the same as for a week-long jaunt. There’s only so much peanut butter you can stand. All raingear leaks. Camp away from the bears.

I learned to squint at a topo map, and see the real mountains. I learned to judge the height of ocean waves, the speed of a river, and the strength of a snow bridge. I learned that humans have poor memories for physical discomfort – and that no matter how many times I feel cold and wet, I will always yearn to head out again.

I learned to see the world at human speed. Sometimes we see wildlife. More often we follow their trails – learning their habits through tracks and sign. We discover new plants, then watch where they grow – glimpses into climate and history beyond the momentary weather. We’ve untwisted the origins of mountains and rivers, and followed the footprints of climate change. We have walked through bustling cities and remote national parks. Scrambled over logging slash in fresh clear cuts and walked beneath helicopters exploring future mines.

Four thousand miles later, at the end of that year-long journey, we found home. Home was a one-room yurt in the small village of Seldovia, on the Kenai Peninsula in Southcentral Alaska. I had a garden full of broccoli and kale, a freezer full of salmon, a yard full of berries, and a crackling woodstove. I had friends and family and an unborn child, growing quickly inside me. And I didn’t know what to do next.

I knew how to plan routes through a complicated landscape of cliffs, water, and brush. I knew how to set up shelter in a blizzard, and start a fire in the pouring rain. I knew how to pare our backpacking gear down to a fine-tuned minimalism. But I knew nothing about babies.

Wilderness expeditions were woven so tightly into the fabric of our lives that I couldn’t imagine giving them up. Yet I couldn’t imagine having an infant along either. The impending arrival of our son presented an obstacle that seemed far more formidable than any ice-choked bay or miles-long bushwhack.

“I don’t know if you could take a baby bushwhacking,” I considered. “Unless you built some kind of shield to protect their face from branches…”

“There wouldn’t be any point taking the baby along on something the baby wouldn’t appreciate anyway,” Hig replied.

As my due date approached, we continued our ignorant speculations. Before I ever saw our child, I was already wondering how to get some time without him.

“How long do babies nurse?” Hig asked.

“I don’t know. I doubt we could leave him the first summer – he’ll only be 6 months old.” “Maybe the next summer?”

“We can do shorter trips, maybe leave him with grandma for a week or two?”

Then our plans met reality – in the form of a seven pound four ounce baby boy with an elfin face and a wicked cone head. Clutching the tiny shape of my newborn to my chest, I no longer fantasized about hiking adventures with grandmother babysitters. I couldn’t possibly leave him behind. I didn’t want to leave him behind. At home, I sat by our woodstove, nursing my baby, gazing at his sweetly sleeping form, and snapping pictures of every tiny flutter of expression. And growing more and more restless with each day. I dug through my drawer of hand-me-down baby supplies for the smallest warmest clothes I could find. We were all going to have to get outside again. Together.

At three weeks old, Katmai’s cry was a high shrill squeal, his face scrunched pink in indignation where it peeked above my half-zipped winter coat. It sent my new mom brain into a frenzied flurry of activity. I pulled a thermarest from my small day pack, plopped down unceremoniously with snowshoes still dangling from my feet, and extricated the baby as Hig threw a down quilt over the pair of us. He started nursing immediately.

The awkward diaper change by unpracticed parents in below-freezing weather went a little less smoothly. Still unused to the dramatic fervor with which babies voice their every desire, I winced at each cry, fumbling in my haste.

After a minute of walking, all was forgiven. We continued for another couple of hours, repeating the nursing break once more – slowly building a new rhythm to our lives.

“See the snow?” I whispered. “I know you’ve never seen anything else, but someday things will be green here.”

At three weeks old, the world outdoors was probably not much more than a monochrome blur of white ground and black branches. It was probably also not much more important – the world beyond mom irrelevant to the tiny infant’s brain. My words trailed off as Katmai fell asleep, and I listened for the small sounds of baby breaths and snores, nearly inaudible over the din of snowshoes on ice. I checked on him obsessively, unsure of the fragility of this new life.

There are times when you realize that your life has irreversibly shifted. For me, those shifts have come walking – out in the wilderness where the seemingly simple task of getting from point A to point B overtakes everything, wiping out all I once thought was important, filling the space of mountains and sky.

Now I was suddenly a parent. Suddenly responsible for a brand new life, in an everyday journey that upends the lives of hundreds of thousands of people every day. It was a shift that promised to be larger than anything we’d ever experienced. Except it wasn’t really a shift at all. Without even knowing it, I’d been training for parenthood for years.

Our journeys had taught me more than just wilderness skills. They taught me to be good at transitions. To be adaptable. To embrace the immediate circumstances, and continue the journey under whatever those new conditions might be.

As the summer months slipped by, our new rhythm evolved. Hig or I would wrap our torso with a several-yard-long length of fabric, carefully knotting it into a shape that could hold a tiny human. From there, the steps proceeded in a never-ending cycle that grew more familiar with every outing.

Tuck baby into wrap, face into mommy or daddy’s chest. Walk a few minutes until baby falls asleep. Continue until the baby wakes and screams.

Pluck him out, nurse him, and pop him back into the wrap, face out this time. Protect baby’s eyes from the bushes as he gets a close-up tour of prickly spruce branches. Try to keep mosquitoes off the baby’s face. Continue until baby screams.

Pluck him out, nurse him, and set him somewhere to chew on a stick. Then pop him back into the wrap, face in.

Repeat.

It seemed like a rhythm that could continue forever. We tested it, stretched it, each day hike a little longer, a little more difficult than the last.

We walked on ice. We walked past newborn lakes. We skated down slopes of scree, past cliffs scratched by vanished ice and decorated with mountain goats. We did all of this in the span of about four days, with our 6-month-old son and my 50-something year old mother.

I winced at each yell, imagining the sound ringing through the thin walls of my mom’s next door tent. Hig walked back and forth and back and forth again, his feet crunching a well-worn path across a moonlit snowfield, with a crying baby snuggled against his chest.

Each time I tucked Katmai into the wrap, I looked back beyond my own memories into the pages of photo albums. My mom, with a long dark braid, hiking through the deserts of Utah, and me, a baby with white-blond hair, smiling from the frame of a Snugli on her back. Her, my age. Me, Katmai’s age.

When I was older, each summer brought pilgrimages to Washington’s Cascade Mountains. While my brother and I carried barely more than our sleeping bags, I remember my mom propping her overloaded pack against a tree, sitting down to strap herself in, and then staggering up with a tremendous heave of leg muscles. We played rhyming games, and games of 20 questions that easily stretched into 200. She coaxed my little brother down the trail with M and Ms.

I remembered making dolls out of lichen and twigs. Catching orange-bellied newts. Pulling my mother into the frigid water of an alpine lake so I could “paddle” a driftwood log across it. My father and I fishing with a scavenged bit of line and a piece of salami – then cleaning the 6 inch trout out of sight of my squeamish mom. Huddling with my cousin in a leaking tent in an all night rain. It was only a few weekends each summer. But those weekends are all that I remember.

As a kid, I’d never thought much about the work it took for my mom to drag us out there – the decades of commitment that stretched from packing babies and diapers into those babies’ grown-up adventures. But now it was my turn.

At 6 months old, Katmai weighed 17 pounds. His diapers and clothes were another 4 pounds. The extra food I needed to make milk for him added another few pounds on top of that. All told, one little baby was responsible for about 25 pounds of the 85 or so Hig and I were carrying between the two of us.

Katmai’s need for nursing breaks, play breaks, and diaper changes was not at all timed with terrain, weather, or anything else. Anything within reach – rocks, grass, poisonous mushrooms – could go into his mouth. His patience with the unpleasant was three seconds long, ending in a wail of wordless and inscrutable complaint. Hot? Cold? Sleepy? Hungry? Bored?

With a baby strapped to my chest, I was perfectly positioned to spend my day nuzzling that sweet-smelling downy blond head. And perfectly positioned to spend my day tripping over my own invisible feet. I took every step twice as carefully – sometimes half as fast. With every patch of brush, I kept my arms extended to keep the branches from scratching his face.

Hig skated down a scree slope, while Katmai grinned and giggled from his chest, utterly unconcerned by the clatter of rolling rocks. He had no complex worries about the future, or the present. He trusted us. He trusted us to keep the bushes out of his face. He trusted us not to drop him on the boulders or ice. He trusted us to keep him warm and fed and dry. Katmai spent his days snuggling his parents and watching the world go by. Each place we stopped, he found new bushes to chew on and new rocks to investigate, his neurons weaving a pattern to mimic the universe.

“He’s so patient!” I exclaimed, near the end of a long day of hiking.

“Actually, he’s not patient at all,” Hig pointed out. “He’s just happy.”

I wondered what impact it had on a baby to spend so much time looking at trees and rivers, rocks and berry bushes, tundra and rabbit tracks… Maybe he would grow to love the outdoors. Or maybe not. But he was too young to tell us, and too young to decide. And maybe wondering about the impact on Katmai was the wrong question altogether. He joined a family of adventurers, therefore he comes on adventures, adapting to the circumstances of his birth like every baby in the world.

The journey had been less than a week. But as we settled back into ordinary life, we found that our dreams had grown. We had stopped thinking about babysitters, and had stopped thinking of waiting. Maybe real expeditions were possible with children after all.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

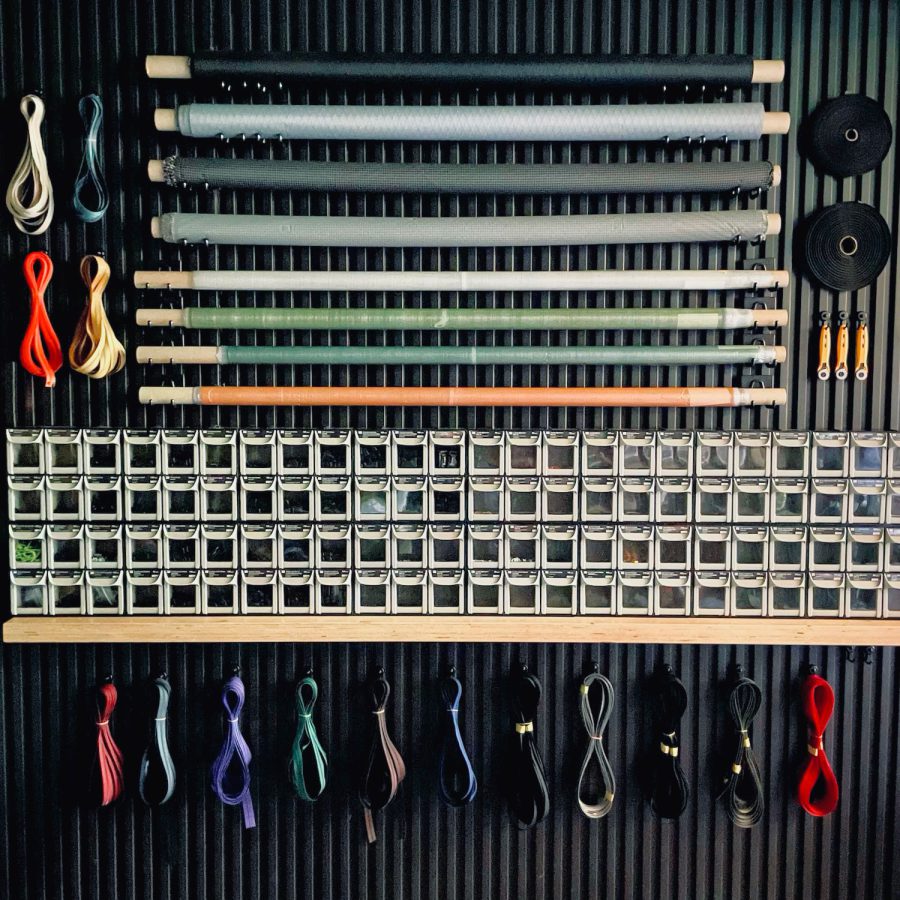

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…

ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…  ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…

ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…  ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…

ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…  ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…

ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…  ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…

ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…  ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…

ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…  ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…

ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…  ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …

ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …