アイルランド・キラーニー国立公園 原生自然の森と湖のハイキング & パックラフティング 2DAYS | パックラフト・アディクト #80

Packrafting in Killarney National Park: A Microadventure Between Storms

Killarney National Park, nestled in County Kerry, is a place of dramatic landscapes—towering mountains, ancient forests, and a series of lakes that reflect the ever-changing Irish sky. The park is home to Ireland’s only native red deer herd and some of the country’s most stunning scenery. In late November, I found myself back in Killarney, a place I hadn’t visited since 2007, this time with a packraft and a plan for a short but memorable adventure.

But, as is often the case in Ireland, the weather had its own agenda. A snowstorm had swept through just before I arrived, briefly transforming the landscape into a winter wonderland. Just some 30 hours later, a torrential rainstorm would cause rivers to flood and fields to disappear underwater. In between, there was an unexpected window of calm—cold, crisp, and windless. It was the perfect, fleeting moment for my trip.

Paddling in the national park requires a permit, which meant a visit to the ranger station. To prevent the spread of invasive species, boats also need to be cleaned before use. Normally, this is done with a high-pressure washer, but I wasn’t sure my packraft would survive such treatment. I called the rangers in advance and arranged an alternative—scrubbing, washing, and disinfecting the boat myself. It ended up being the cleanest my packraft had been since I first unpacked it.

Originally, I had planned to walk to the ranger station, which would have taken me around two hours, but work held me up until late afternoon, and I started to run late. I called them and was told that I had a maximum of an hour before the station closed for the day. So, instead of a leisurely hike, I had to grab a cab. The driver, a Killarney local, had no idea the ranger station even existed, which was surprising given how small the town is. He told me that he would not usually travel much outside this busy tourist town but was happy to help me as there were not many customers that day.

After a bit of navigation help, we found the right place, and I presented my packraft for inspection. The rangers were satisfied with how well I had cleaned it (I also showed them some videos as proof), though they seemed sceptical of the boat itself. Hard-shell kayaks and canoes are the norm here—my packraft, to them, must have looked more like a pool toy. They even asked me to sign a waiver of liability (though I think everyone is asked to do that).

The rangers also strongly advised me to stay on Muckross Lake, the smaller of the two, warning of large waves on the bigger Lough Leane and sharp rocks on the river upstream. While I would have loved to paddle across to Innisfallen Island, where I had once visited an old abbey by boat in 2007, I decided to follow their advice. After all, they knew the area best.

With the short November daylight slipping away, I hiked back towards the town and into the park. My first stop was Muckross Friary, a centuries-old ruin wrapped in gnarled yew trees. I had visited it before but didn’t remember much. A quick phone call to my wife, who had worked in Killarney as a student for several summers, brought back memories—she recalled the abbey fondly and asked me to take lots of pictures, which I did.

As the sun dipped lower, I walked toward the shores of Lough Leane. The moment I arrived, the scene took my breath away. The water was mirror-flat, reflecting the snow-covered mountains perfectly. Mist rose in delicate tendrils from the surface, and the whole lake was bathed in golden twilight. The “big waves” I had been warned about were nowhere to be seen.

Unfortunately, I could not stay long to enjoy the view. Darkness fell quickly, and I continued hiking along the path, my torch cutting through the night. It was even darker as the path took me through a forest. In Ireland, large forests are rare, but Killarney National Park still holds remnants of the ancient woodlands that once covered the island. Some places had signs reminding visitors to stay on the paths to protect the delicate ecosystem, so I carefully followed the trails. Eventually, I found a small side track leading to a perfect hammock spot. The cold night air (-1°C) wrapped around me, but I was prepared. With only the distant calls of birds and the soft rustling of leaves, I quickly drifted off to sleep.

The next morning, I lingered in my hammock, savoring the quiet and the sounds of the waking forest. There was no rush—the day’s hike and paddle were both manageable. It was also good just not to do anything for a while. When I finally packed up and started walking, the morning light made the landscape even more beautiful than the evening before.

Crossing a narrow bridge that linked Lough Leane with Muckross Lake, I met an elderly man in his seventies out for a walk. We had a brief conversation, and he said that he lived in Killarney—he pointed across the bigger lake to his home. I also asked him to take a photo of me—a rare occasion when hiking on your own. For a short moment, we walked together, chatting about various things big and small, but his pace was much quicker than mine (in my defense—I had a lot more I had to carry), and, once we reached Dinis Cottage, I decided to stay there for a short while, whereas he continued further.

The reason why I wanted to stop at Dinis Cottage was that a short distance behind it was the so-called “Meeting of the Waters”—the point where the river coming from the mountains split in two, one stream flowing into the large lake, the other into the smaller one. Back at the cottage, I was surprised by another encounter—a beautiful little robin flew and sat just in front of me as if demanding that I feed it. I decided to have a short break for a snack and share some of it with the brave bird. So, I stretched out my hand with some crumbs, and it landed briefly on my palm to grab the food before flying off again.

Just a bit further, I took another detour. I crossed Old Weir Bridge—a stone bridge over a rapid that brought me to the other side of the river, after which the path disappeared into the wet boggy terrain. At first, I tried to find a way to hike upstream to find a nice put-in spot, but the ground was so wet that I quickly changed my mind and returned to the main path. The view from the bridge was stunning, though, and definitely worth the detour.

Later on, I attempted to find a shortcut to the main road a few more times, but the path was flanked by a high wall of rhododendron—an invasive plant that the rangers fight a losing battle against—which looked impenetrable. I was left with no choice but to continue along the main path and onto the road.

After the hike of about 7 kilometers, I reached my put-in spot at the shores of the Four Friends, a narrow section of water that eventually goes to the lakes. I inflated my packraft, packed my gear, and pushed off. As I rounded a bend in the river, I noticed movement up on a hill. A large stag was standing there, watching me. A few female deer were next to it. I stopped paddling and let the current carry me downstream so I wouldn’t startle them. It stood completely still, just staring at me. A bit later, I saw several other similar groups of deer, but the first stag was the most impressive.

The water was calm, the wind gentle, and the snow-dusted mountains provided a breathtaking backdrop. At one point, I passed beneath Old Weir Bridge, beneath which a small rapid flowed. The rangers had warned me about sharp rocks, but at this water level, the passage was smooth. The so-called dangerous rapids were no trouble at all. (Or were they talking about other rapids?)

Muckross Lake was just as calm as Lough Leane had been the night before. I briefly considered paddling to the larger lake, but with daylight hours slipping away, I decided not to. Instead, I explored the lake’s northern shore, where jagged rock formations created small caves along the waterline. I tried to explore some of them, but I had to be very careful, as the stones were razor-sharp—now I understood the warnings that the rangers gave me. Any contact with these rocks would have been disastrous for my packraft.

Feeling hungry, I spotted a small sandy beach, an ideal spot for a break. The pine trees and soft sand almost made it feel like a warm-weather destination—except for the fact that it was close to freezing. After a warm meal, I paddled the final stretch toward an old boathouse where I planned to take out. Just before reaching it, I saw a father and daughter on a traditional wooden boat with a motor—these were the only people I had seen on the water all day.

With my paddling complete, I packed up my gear and started the short walk toward Muckross House. Along the way, I exchanged pleasantries with a few hikers, all of whom were equally delighted with the unusually good weather. They were right—by that evening, the promised storm arrived in full force. Rain poured relentlessly, and the next morning, as I sat on the train to Dublin, I watched some fields and roads disappear beneath floodwaters. My timing for this trip had been perfect.

Altogether, I had hiked about 13.5 km and paddled 5 km—not the longest trip I’ve done, but certainly a rewarding one. It had been a compact, 24-hour microadventure, my first time paddling in Ireland. The beauty of Killarney National Park, the solitude, and the feeling of perfect timing made it a trip to remember. Let’s see what I can paddle in Ireland next.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

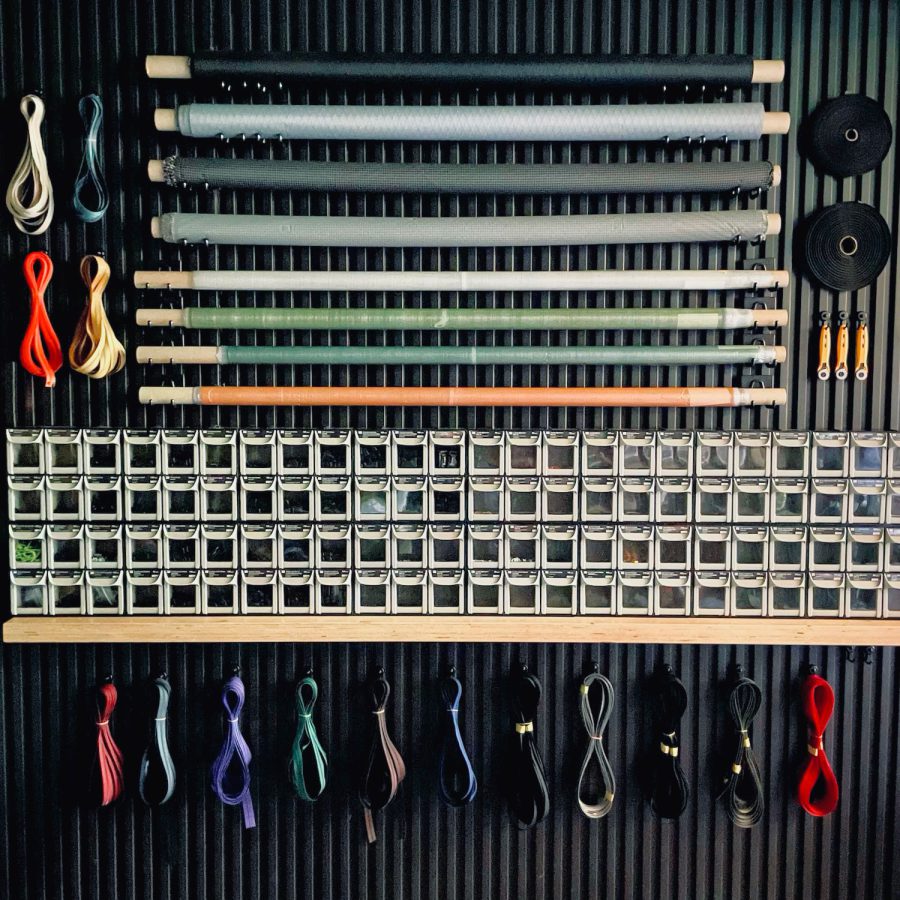

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…