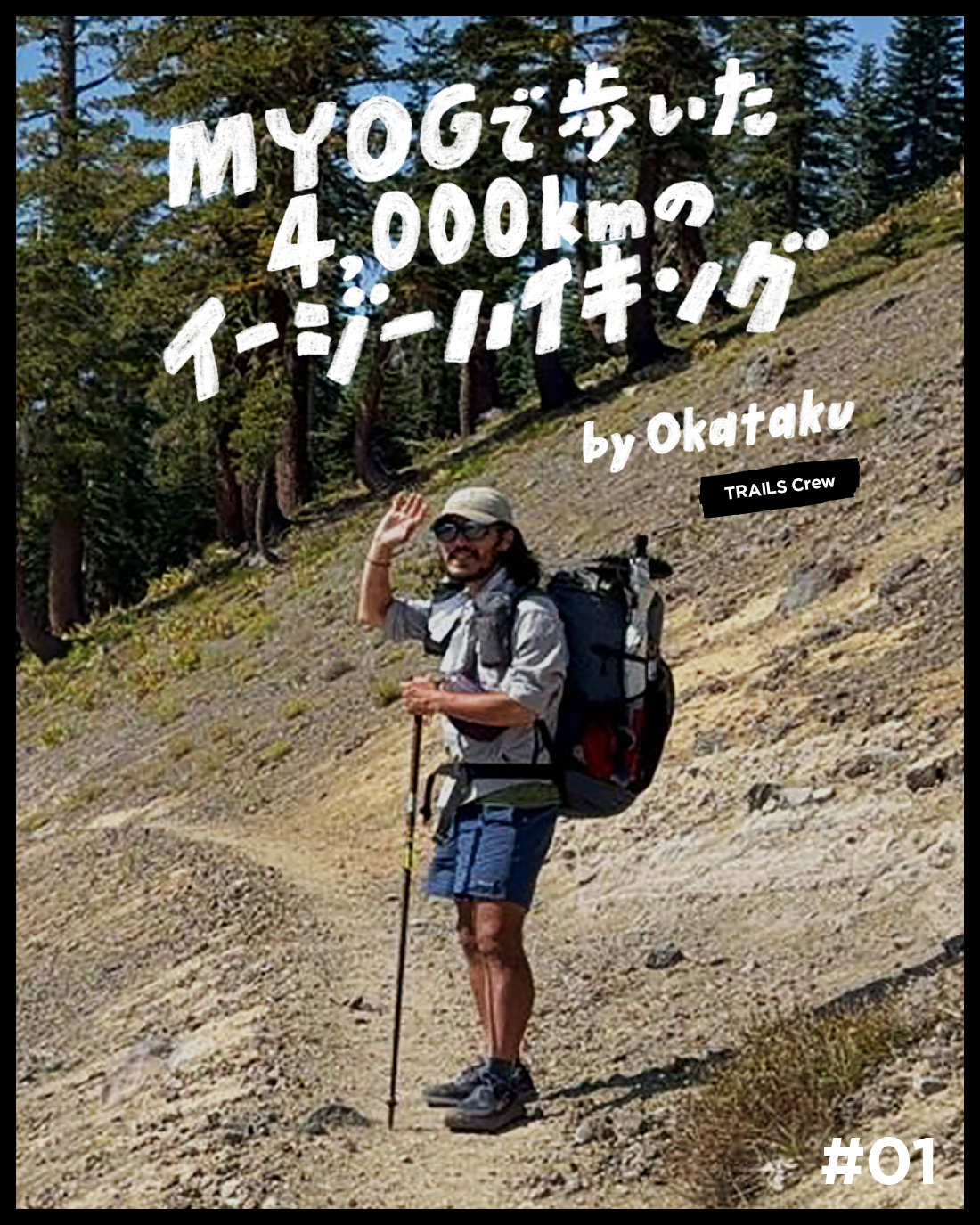

take less. do more. 〜 ウルトラライトとMAKE YOUR OWN GEAR by グレン・ヴァン・ペスキ | #05 最軽量を目指した「G5〜Whisper〜Murmur」の実験と試行錯誤

Lighter and Smaller: Design of the G5 Pack

G5_in_Wind Rivers_Range

The process that resulted in the design of the G4 was outlined in my previous article [link]. That pack, my fourth design, was suited my needs and the rest of my gear at the time that I created it. I put the plans on the internet so other people could sew them, and eventually launched GVP Gear (now Gossamer Gear) as a way to allow people to buy the pack ready-made instead of making their own.

One of the problems of being an engineer is that you can’t leave well enough alone. This can be a good thing, as it results in refined designs and advancements in product performance. As I continued to do hikes with our son Brian and the Boy Scout troop, and as I hiked sections of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) with my buddy Read Miller, I continued to work on lightening my load.

My gear lists for this period, from 2001 to 2004, show a transition from the G4 to the G5 pack. My pack weight was getting a little lower. A large part of this reduction was me realizing there was gear I could do without. Some of the reduction was from moving from synthetic insulation in clothing to down insulation. Besides being lighter, down clothing meant that I needed less space. I had always been very careful with my gear, so I created the G5.

Glen with G5 in Beartooths

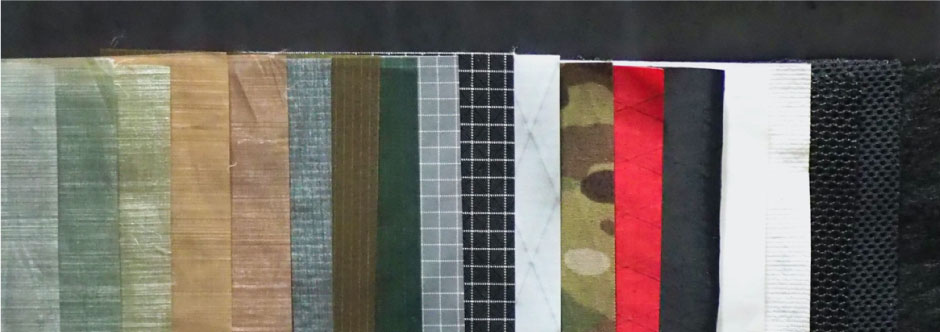

For the G5 pack, my goal was to reduce pack weight using lighter materials for construction. When I was sewing the G4 pack, the lightest fabric generally available was 2.2 oz. urethane-coated nylon. I was talking one day on the phone with Quest Outfitters in Florida, talking about my need for a lighter material.

G5 packs in Beartooths.

Since they were located in Florida, they were familiar with the sailing industry, and they suggested I look to sailcloth manufacturers for lighter weight material. The sailing industry makes huge sails, so the weight of the fabric quickly adds up. I ordered some spinnaker fabric from Challenger Sailcloth, and started sewing prototypes. We became the first outdoor company to use sailcloth for backpacks and shelters, which 20 years later is now common practice.

Glen at PCTA 2002 Annual Meeting with G5.

In creating the G5, I wanted to make it smaller as well as lighter, but I still liked the basic features of the G4. So the G5 had a roll top closure, an expanded bottom for the sleeping bag, huge side pockets, a back panel that used a folded sleeping pad for the pack frame, and shoulder straps and waist belts that allowed for the insertion of unused clothing to provide padding.

G4 and G5.

The spinnaker material was about 25% of the weight of the nylon used in the G4. But there’s not that much fabric in a pack, so I used further measures to reduce weight:

The drawstring in the top of the extension collar was eliminated.

5/8” (16 mm) webbing instead of ¾” (19 mm) webbing for the shoulder straps.

1” (25 mm) webbing instead of 1.5” (38 mm) webbing for the waist belt.

Spinnaker fabric instead of heavy mesh for the large side pockets.

Much lighter weight mesh for the back mesh pocket.

Narrower shoulder straps and waist belts.

Dramatic reduction in the areas having the more durable Oxford cloth.

Glen with G5 in snow Beartooths 2004.

Using lighter materials required more careful consideration of where the stresses were in the design. Typically the backpack load of the backpacker’s gear contains major stress points at the connections to the shoulder straps, particularly the upper end of the shoulder straps where they join the pack body. And to a lesser extent, the stress created by the load on the waist belts where they join the body of the pack. As far as abrasion, the pack can experience this in almost any exposed location, but I focused on just the very bottom of the pack. I figured when I took the pack off and set it down, that’s where I wanted the more durable fabric. I became known on some trips, where there was bushwacking through dense willows or other brush, for taking off my pack and holding it over my head, letting my body take the brunt of the brush while protecting the delicate fabric of my pack.

XUL on PCT with G6.

All these design features resulting in reducing the weight of the G4 at the time of 12 oz. (340 g) to about 6.4 oz. (180 g). As I continued to hike, I continued to gain experience, and to refine my gear choices. I gathered data on every trip as to what worked, and what didn’t work.

Ryan Jordan “Light weight Backpacking and Camping”.

Gear on sub-3 trip on PCT.

When the G5 pack was reviewed by Ryan Jordan in BackpackingLight, he thought it was too heavy. He advocated for a simpler version. I created a very minimal pack, removing the waist belt, the pad holder, the side pockets. This pack, the G6, also known as the Whisper, was only made very briefly. The G6/Whisper, made out of the same blue spinnaker fabric of the G5, weighed only 3.6 oz. (102 g). I used it in 2006 for a trip on the PCT with a base pack weight of 2.89 lbs. (1.3 kg). But for most of my trips, not having side pockets was just too inconvenient. I am a proponent of reducing pack weight as much as anyone I think. But there comes a point where the function suffers. There is a term called “fuss factor”, to describe the amount of trouble and effort it takes to do something. Sometimes, for me at least, the “fuss factor” involved is not worth the weight saved.

G6 (Whisper) anad Murmur.

I ended up sewing side pockets onto a G6 and using that for trips. In fact the only G6 that I still own has side pockets on it (although an original G6 hangs on the wall at The Trails Magazine). This pack eventually became the Murmur, first prototyped out of the same blue spinnaker fabric, and eventually moved to a more durable Robic nylon when it went into production.

Current Murmur.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

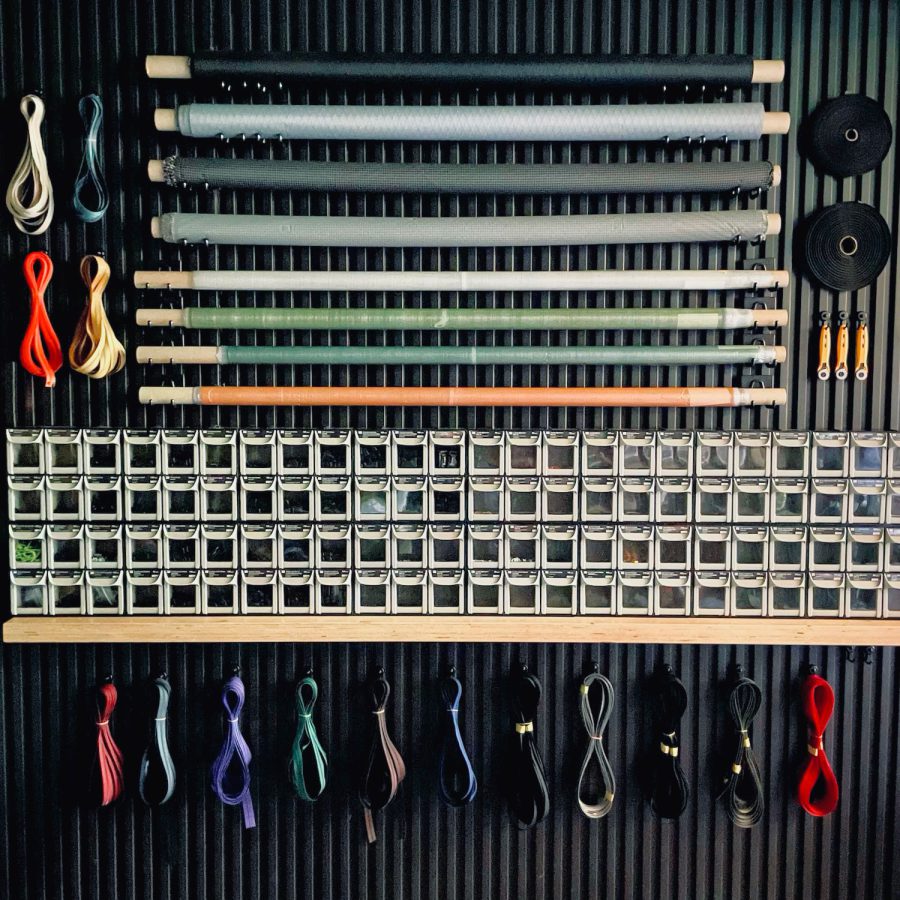

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)

Tenkara USA | RHODO (ロード)  Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)

Tenkara USA | YAMA (ヤマ)  Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…

Tenkara USA | Rod Cases (…  Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…

Tenkara USA | tenkara kit…  Tenkara USA | Forceps & …

Tenkara USA | Forceps & …  Tenkara USA | The Keeper …

Tenkara USA | The Keeper …  Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …

Tenkara USA | 12 Tenkara …  Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…

Tenkara USA | Tenkara Lev…