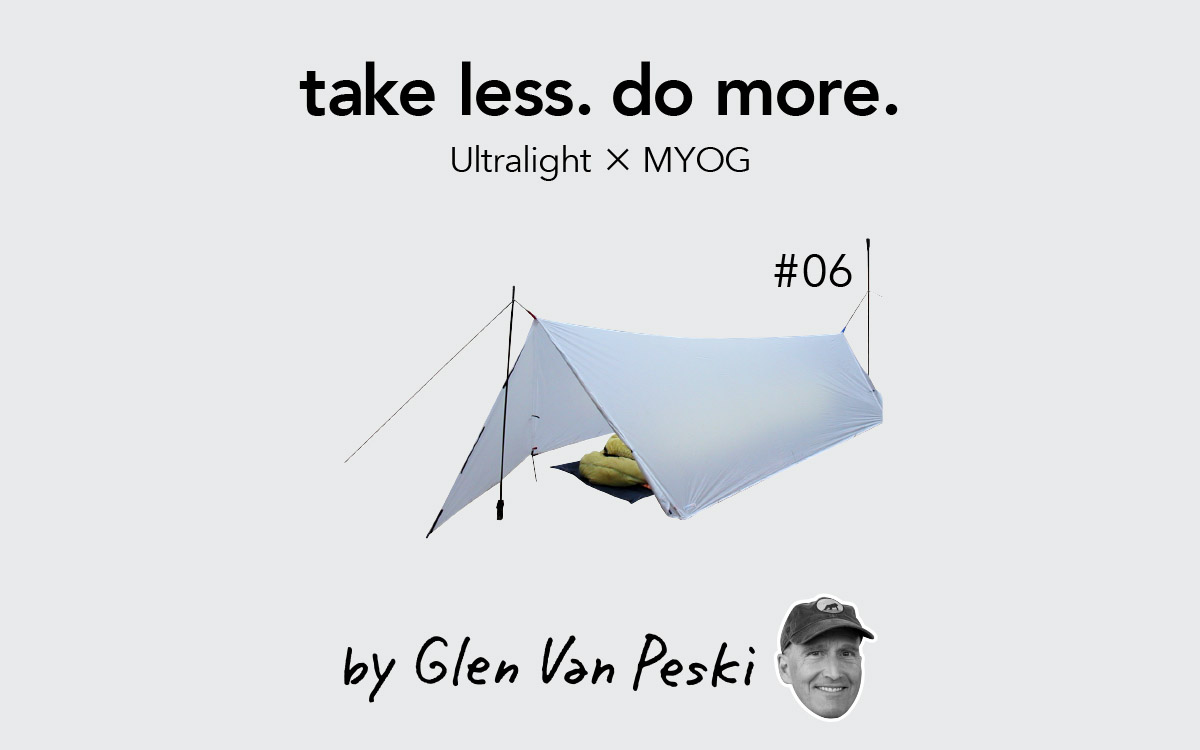

take less. do more. 〜 ウルトラライトとMAKE YOUR OWN GEAR by グレン・ヴァン・ペスキ | #06 新しい素材の実験と徹底した合理化から生まれたULシェルター「スピンシェルター」。

Design of the Spinnshelter

The email came from an Ultralight friend in the UK, and the subject was “You’re Infamous”. The email contained an article, written by an author in the UK, talking about the dangers of embracing the [at that time] new fad of Ultralight Backpacking. To illustrate, it included a photo of me with Ryan Jordan and Alan Dixon of BackpackingLight, in the middle of the Wind River Range of Wyoming, in tarps covered with snow.

That trip, hatched by Ryan as I recall, was an extremely light trip. Being somewhat competitive, we had been going through our gear relentlessly in the motel room prior to starting the trek. With food, all three of our packs for the trip weighed under 45 lbs. (20.4 kg) combined. We knew there was a storm coming in, and that it would hit right in the middle of our Wind River traverse from Green River to Big Sandy, through Cirque of the Towers. It hit us the night before we went over Texas Pass.

The thing was, we weren’t in trouble. We were all experienced tarp users, we were dry, warm and safe, and proceeded to pick up and hike over Texas Pass, and camped near Cirque of the Towers as the second half of the storm hit us.

For someone trying to shave pounds off their pack weight, a tarp is attractive, but it does come with a learning curve, though less of one these days. My first tarp experience was riding my bicycle 4200 miles (6,700 km) across the United States in 1976. I sewed a tarp from 2.2 oz. ripstop nylon and used it that summer, where it kept the rain and hail off me as I slept in my nylon cord hammock. So in the early 2000’s, after creating the G4 pack [link to article], and while using advances in materials to create the G5 and G6 packs [link to article], it was time to start also working on shelters. One of the iconic early offerings in this space was the Integral Designs Silshelter. At 12.9 oz. (366 g.), it utilized the new silicone-impregnated ripstop nylon, or silnylon, to save weight. I had a Silshelter, but it took some creativity to get a storm-worth pitch, at least with the early design, due to the large opening in it.

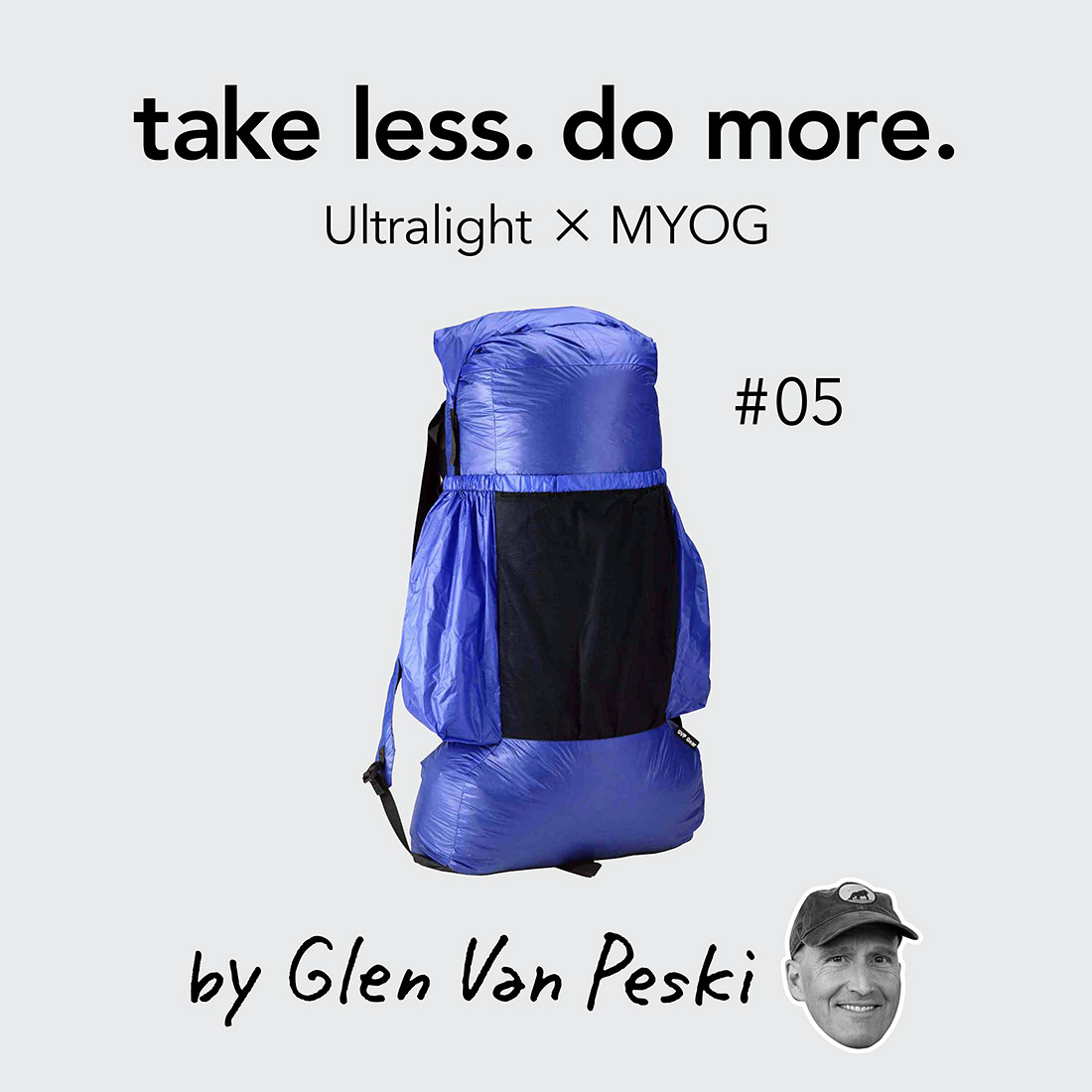

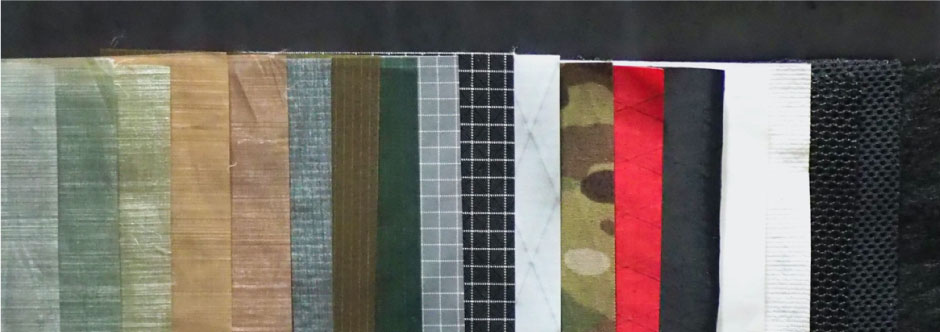

I wanted a little more protection, and being tall, wanted something longer. I was also wanting to take advantage of the lighter materials I had located for the design of the G5 and G6 packs. One of the early issues with using spinnaker fabric for shelters was waterproofness. In a pack, I used a liner bag to provide rain protection, so the fabric didn’t have to be waterproof. The sails which were the intended use of the fabrics also didn’t need to be completely waterproof, so that wasn’t a specification that the fabric designers were optimizing for.

We ordered different sail cloth fabrics from Contender, Challenge and Dimension Polyant. We had very crude testing in those days… I would scoop a few gallons of water from my pool in San Diego into the fabric, tie it in a bunch and hang it from the pool fence, then monitor to see how it leaked water. The weight of the fabric was great, just under 1 oz. per square yard for some samples (34 g/ sq. m.), but it was hard to find something that was waterproof enough for a shelter.

As far as design, I wanted something long enough for me at 6’4” (1.93 m), with a vestibule for gear. I settled on a design with a front entry, roughly an ‘A-frame’ design, that tapered to a smaller height and width at the foot end. I used one trekking pole at the high point, and since the low point was shorter than a trekking pole, I used a trekking pole set away from the foot end to pull that end up and out. I made a long sloping vestibule for shedding wind, and sewed Velcro along the edges to close it against the wind and rain.

I had lines on the base tie-outs, so it could be set up with clearance above the ground. This helped make it roomier inside, and also provided the best ventilation. Single wall shelters are notoriously subject to condensation, although I was living in, and mostly backpacking in, the relatively arid western U.S. At the foot end, the design varied over the years. At one point I had a smaller, peaked design to shed wind. Then to save fabric and stakes, I made the foot section with a flat covering between the two sides. To provide flexibility, at one point I added Velcro to this panel, so based on conditions, you could either leave it open for additional ventilation, or close it for additional weather protection.

This shelter was named the Spinnshelter, in a nod to the Silshelter beginnings, updated to reflect the use of spinnaker fabric, as well as design enhancements. This early white shelter featured in the 2005 Lighten Up! video. My gear lists for trips from September 2001 through March 2003 list a ‘GVP Gear Spinnaker Shelter’ weighing 9.6 oz. (272 g.), and it shows up in trip photos from that period. By 2004 I had moved to a slightly lighter spinnaker fabric, the same fabric used in the construction of the G5 and G6 packs. This blue fabric, along with design refinements, brought the weight of the Spinnshelter down to 8.9 oz. It was a crude design by today’s standards, but for years later, whenever I set one up, I was pleasantly surprised by the protection it provided for minimal weight. Sadly, my current collection doesn’t include a Spinnshelter, I must have given it to someone.

The Spinnshelter did not provide protection against bugs, so by 2007 I was at work on prototyping The One, which provided a bathtub floor and full mesh protection, albeit at a weight penalty, as the early prototypes weighed 17 oz. (482 g.). At the same time, for conditions where bugs were not expected, and where I most likely wouldn’t be in storms, I started working on The Wedge, a much more simple and dramatically lighter side-entry tarp.

- « 前へ

- 2 / 2

- 次へ »

TAGS:

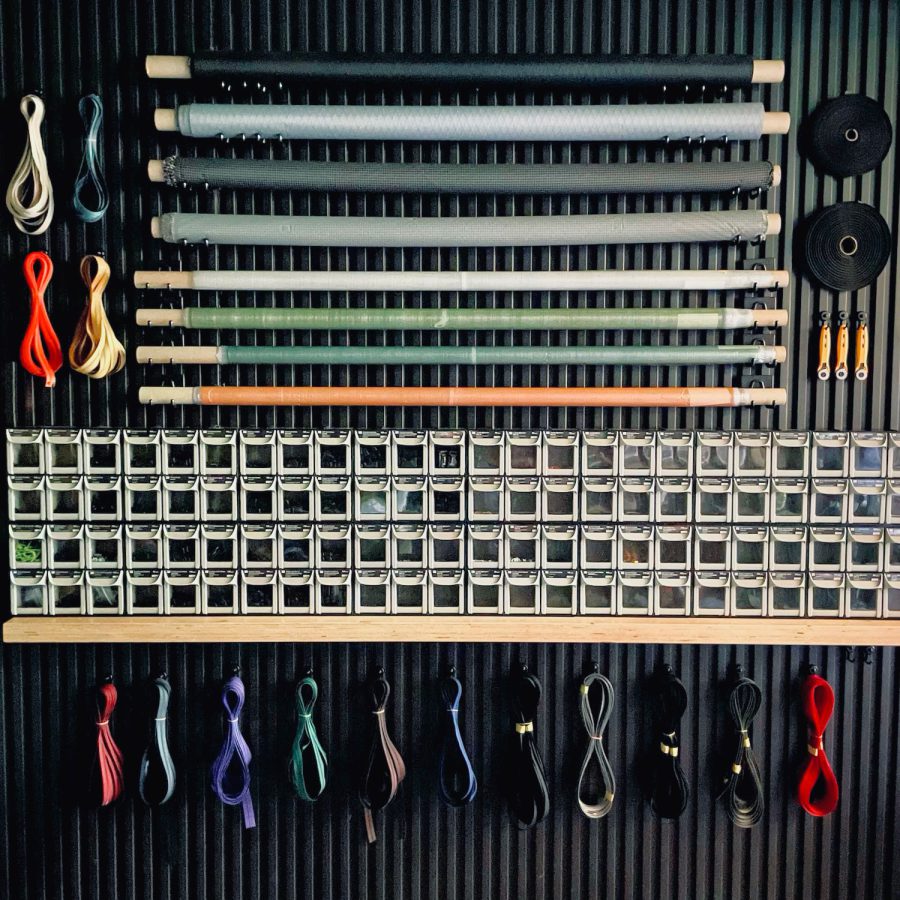

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…

ULギアを自作するための生地、プラパーツ、ジッパー…  ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…

ZimmerBuilt | TailWater P…  ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…

ZimmerBuilt | PocketWater…  ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…

ZimmerBuilt | DeadDrift P…  ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…

ZimmerBuilt | Arrowood Ch…  ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…

ZimmerBuilt | SplitShot C…  ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…

ZimmerBuilt | Darter Pack…  ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…

ZimmerBuilt | QuickDraw (…  ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …

ZimmerBuilt | Strap Pack …